Summary

As of 15 May 2020, there are 181 confirmed cases of individuals with Covid-19 in Myanmar, with six reported deaths. The spread of the virus is only at its initial stages, and given Myanmar’s underdeveloped public health infrastructure, the impact is expected to be significant: 23% of Myanmar’s population have underlying health conditions,[1] placing that group at high risk of severe symptoms if they contract the disease. Further, the effects of the virus on household income are also expected to be severe. In a recent survey, 54% of respondents stated that their employment had been stopped, and that figure rises to 60% if just households are examined without Medium, Small and Micro-Enterprises (MSME) owners (38%).[2] The announcement of a $2 billion package (USD) to fund the Covid-19 Economic Relief Plan (CERP) has not allayed concerns of the economic difficulties that lie ahead.[3] A broader set of social challenges, such as a rise in domestic violence associated with lockdowns,[4] accompany these public health and economic difficulties.

The disease itself and the response to it may also widen pre-existing cleavages in society. For instance, the prevalence of the disease in certain ethnic or religious groups may result in increased stigma, particularly if those groups face pre-existing prejudices.[5] Initial evidence also points to a resurgent nationalism amongst the Bamar majority, many of whom believe that the Government’s response has been excellent,[6] while the community perception in ethnic areas often contrasts starkly. In addition, in areas in the country’s periphery where there have been long-running and entrenched conflicts that have intensified since the onset of Covid-19, particularly in Rakhine and Chin States, the risk to response actors themselves is significant. The killing of a World Health Organization (WHO) worker in Rakhine in April 2020 underlines this risk.[7]

The response will have further implications on power and governance as it will be subject to politicization between contesting authorities. The response may be taken by actors as an opportunity to assert influence within a wider contest for control between ethnic armed organisations (EAO) and the Government. Relatedly, the heterogeneity of community allegiances and beliefs in Myanmar adds more complexity to how the response is conducted. For instance, communities with lower trust in the Government may demonstrate a lower compliance with behavioural advisory issued by authorities, similar to the community responses observed during the Ebola outbreak in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC).[8]

Engaging parahita groups as part of the health and economic-focused Covid-19 response presents both opportunities and challenges. On the one hand, these groups are uniquely positioned in Myanmar to respond to threats, given: their presence down to an extremely local level; the speed with which responses can be conceived and delivered; and the trust that communities have in them to deliver a response, thus not limiting operational space. However, such partnerships are also fraught with risks. These include: lower administrative capacities that do not align with donor standards; affiliations to hardline ideologies; and risks to parahita organizations themselves given varying levels of anti-internationalist sentiment in Myanmar.

Engagement with parahita actors thus should only be undertaken with a deep understanding of specific organizations and where collaboration with external partners will have an added value on the service output in a safe and conflict sensitive manner. International response actors should therefore consider this report as another step in an iterative process of potential engagement with parahita organizations.

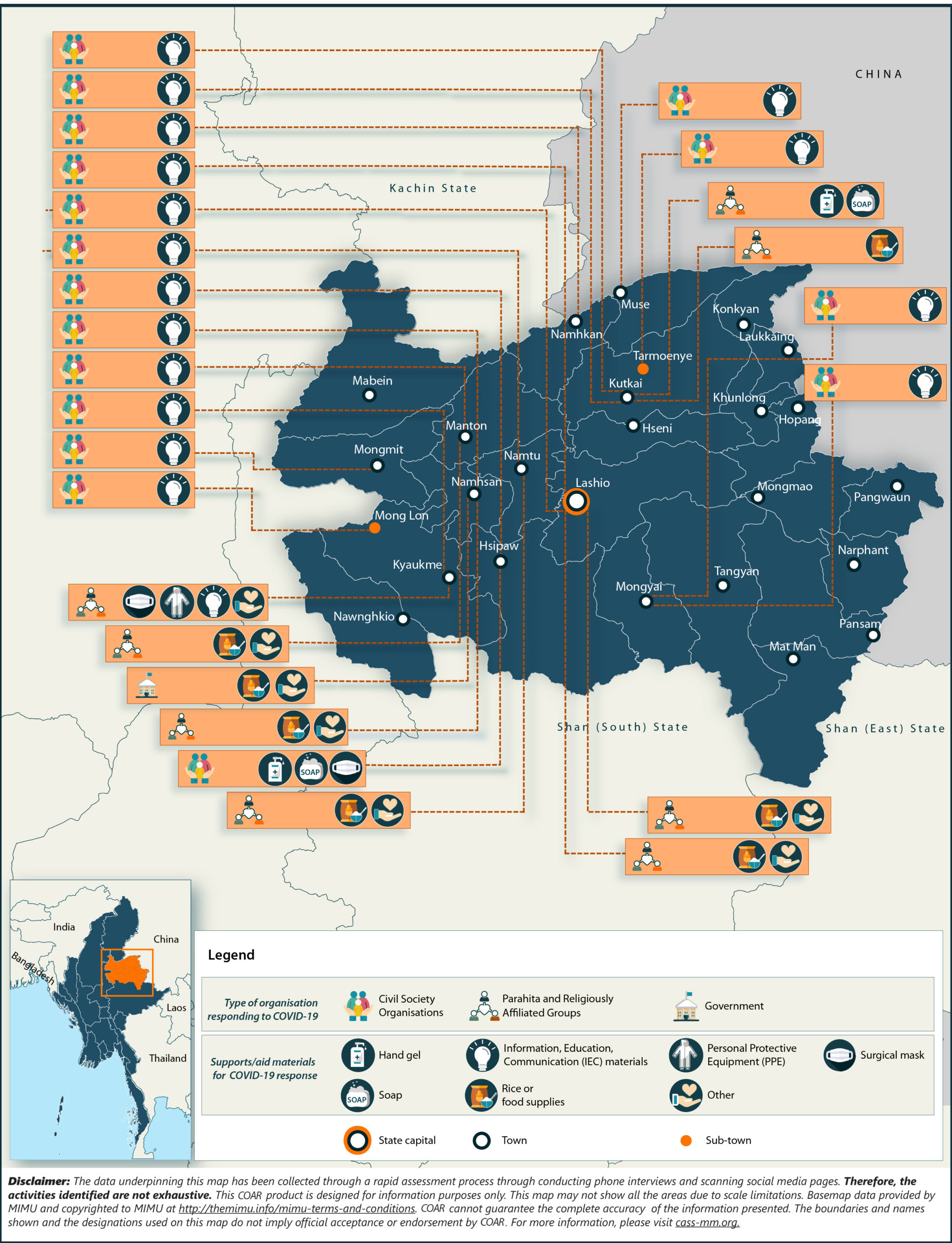

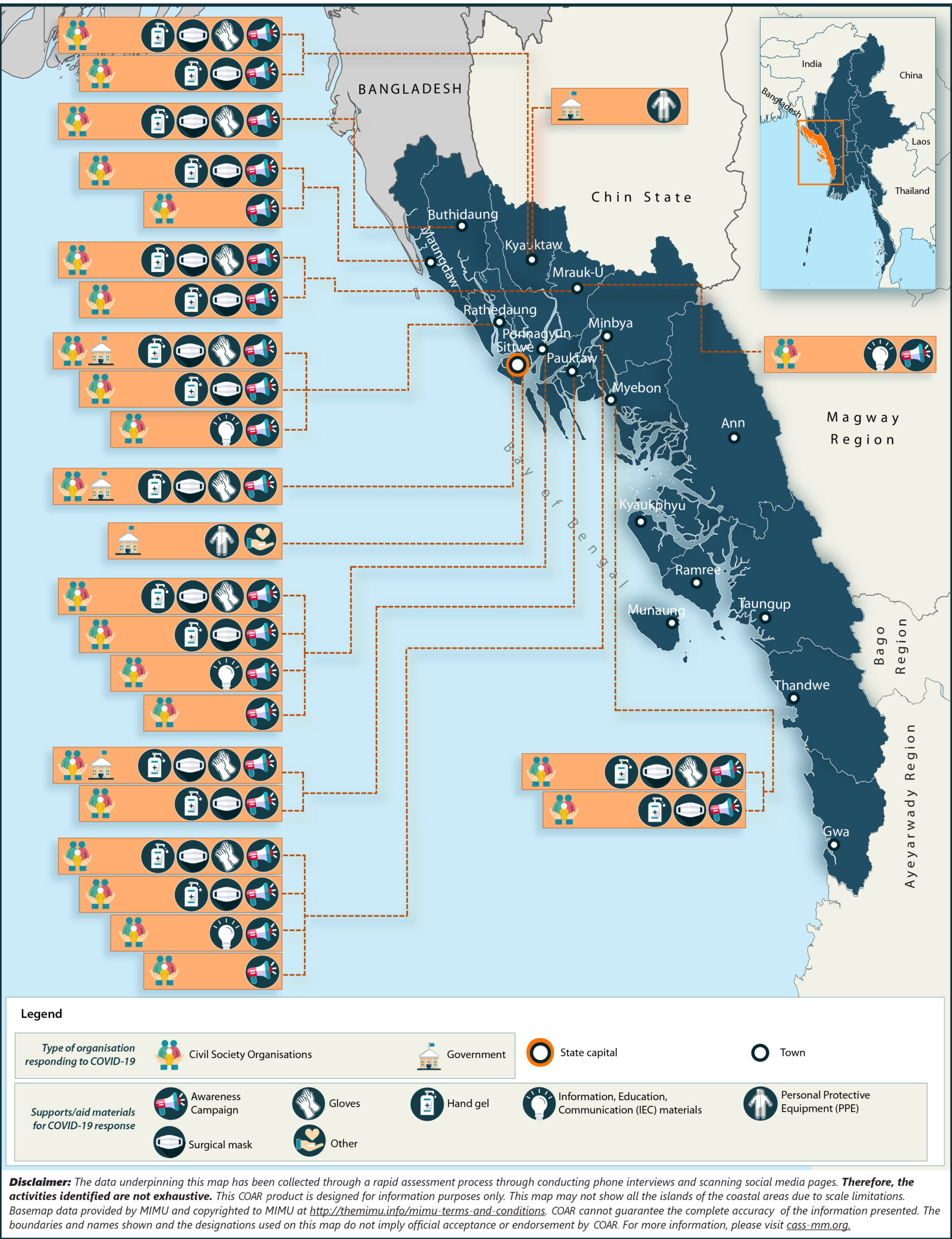

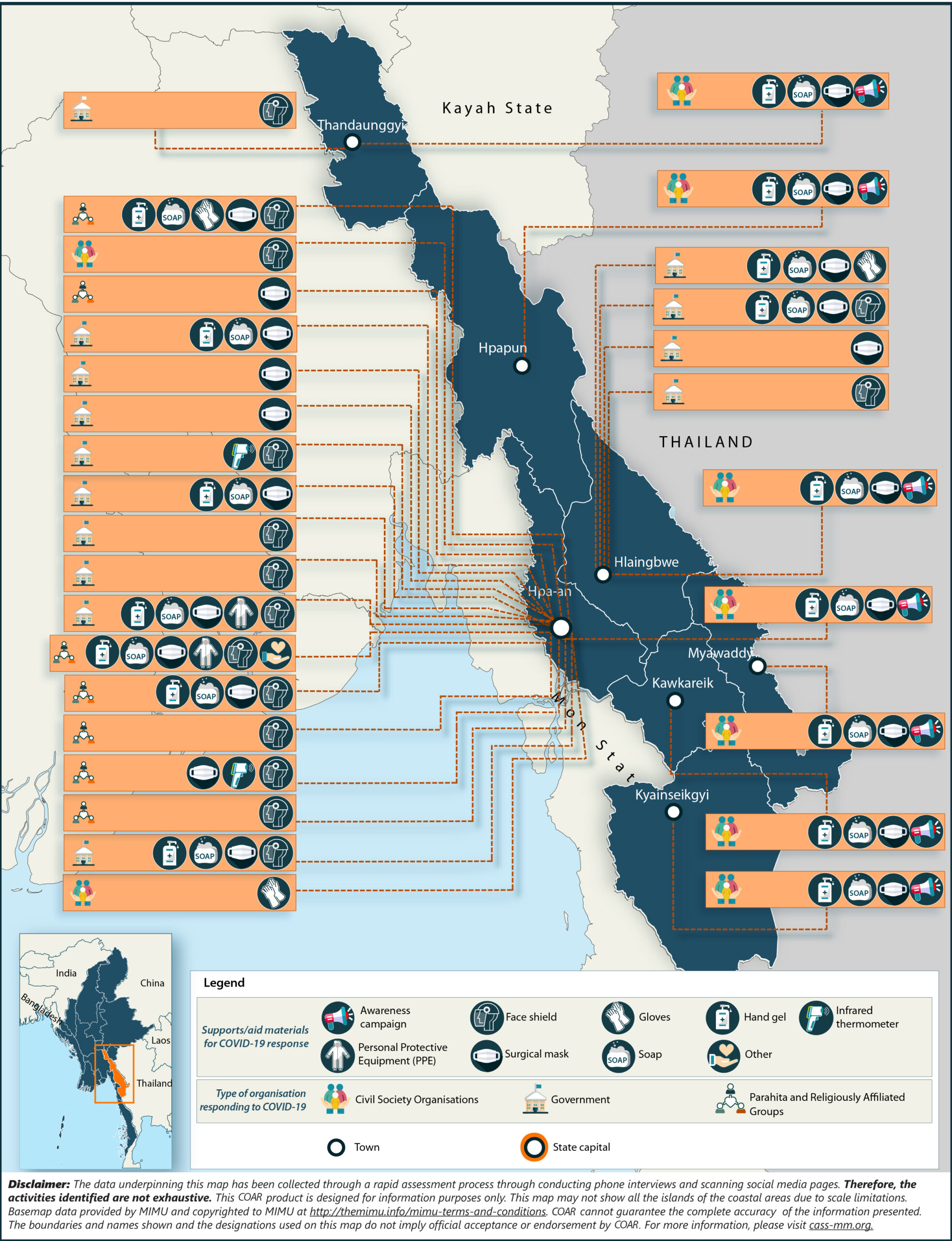

This report offers an initial overview of the response of these parahita groups to Covid-19 in three conflict-affected areas in Myanmar: northern Shan State; Rakhine State and Kayin State. These sites were selected by partners in the Humanitarian Assistance and Resilience Programme – Facility (HARP-F) due to the presence of vulnerable populations. Their vulnerability to Covid-19 is defined by their underlying poverty, conflict-affectedness, and location in border areas where population movements, including to and from other nation-states, is likely to be a factor in the spread of the disease.

As per a previous research on parahita actors in Myanmar:

Parahita organizations often play a crucial role in responses to emergent disasters in Myanmar. Mostly, but not always, founded on religious principles, they are often the ‘first-responders’ in emergency situations, functioning as both early warning and needs assessments at an extremely local level, as part of a devolved structure that link up to a township, state, or sometimes Union-level organization. Parahita, most directly translated to ‘altruism’, fundamentally reflects a volunteer mindset in support for the benefit of others. While the extent of organization and scope of activities vary across different religious groups in Myanmar, they function with roughly similar operating models whereby donations are collected from community members of the same religious affiliation, to then purchase goods and/or services for groups that are vulnerable to the threat.

Key findings & recommendations

Findings

- Parahita and religiously-affiliated organizations have delivered assistance rapidly, namely in donating food (rice and cooking oil), and to a lesser extent personal protective equipment (PPE), soaps and other sanitation equipment, as well as information products, to communities across the three regions examined.

- In the areas where research was conducted, trust in government was low, eliciting an often-strong community-led response, particularly in Rakhine State.

- Some places of worship – churches, mosques, temples and monasteries – have been opened for use as quarantine centers.

- However, many have not, and this is in large part as an effort to protect senior members of clergies from exposure to Covid-19. This has been especially true for religious sites in Rakhine State. There have also been limitations set by the Government on certain religious networks, which is likely to result in a shortfall in services in places such as rural Kayin and urban Sittwe.

- Accurate information and health advisory information remains a key issue. In central and northern Rakhine, where mobile internet service is blocked, the problem is more acute. In Northern Shan and Kayin States, much health advisory information has been translated, though has not been effectively distributed into areas where ethnic minorities are located, such as in Pa-O and Palaung.

- There is a significant disparity in the services available to communities in urban versus rural areas. Those residing in very remote areas lack support, including access to information.

- Concerns around migrant workers returning from Thailand exist across all regions, not just in Kayin State. The 21-day mandated quarantine in these areas is designed to address those concerns, though will now need rigorous implementation in order for those concerns to be allayed.

- While coordination amongst different parahita groups is strong, particularly in Kayin State, coordination between Township Medical Offices (TMOs), the General Administration Department (GAD) and ministries is much weaker. Coordination between these entities is particularly weak in Rakhine State.

- Coordination between services run by the Government and those by EAO’s is perceived to range from non-existent to weak. Perceptions of the efficacy and legitimacy of these response actors are in flux and may have implications for broader prospects for peace.

- All parahita groups interviewed expressed interest and saw utility in engaging with international actors to varying degrees from informal coordination to full partnerships, particularly in providing assistance to very remote rural areas, where there are concerns that communities are being overlooked.

Recommendations

- At a minimum, international partners should seek to improve communication and coordination with parahita groups. Inaction on this front constitutes a conflict insensitive practice, where local actors and activities are ignored.

- International partners should build on the communication channels with parahita organizations and religious institutions in these areas to develop a highly-localized and nuanced understanding of their capabilities, needs, and risks associated with engaging parahita groups further on Covid-19 responses.

- Given that some parahita groups are not operating as they would in response to other crises, gaps in service provision are very likely to form. It is only through a process of undertaking recommendation 1 that international partners can develop an understanding of where and when those gaps are likely to form, and thus deliver services most effectively.

- Any engagement of parahita groups should be contextualised in the existing conflict dynamics of the region. Local perceptions of support will emerge as parahita groups are often active stakeholders in local contests for legitimacy and power.

- Parahita groups with links to extremist ideologies in particular should not be engaged to avoid strengthening these voices in the longer term.

- Parahita groups and similar religious organizations are largely if not completely reliant on community donations. Critically, in Myanmar, 62% of the population report having no savings.[9]As the economic strain on households becomes more acute, the capacities to donate will diminish and thus support to wider communities will reduce. As such, international partners should prepare support to fill these gaps as the crisis protracts.

- International partners should pay close attention to how this support is conceived and delivered particularly in contested areas and among displaced communities where the attention on the equity of aid is already high.

- International partners should prioritize the dissemination of information and guidance material in remaining ethnic minority languages to ensure that those communities are not overlooked. The spread of misinformation into information vacuums is a real threat to an informed and measured public response to the onset of the disease.

- Deliberate and concerted efforts to reach rural and remote communities will need to occur if swathes of vulnerable groups are to be included in measures to shield them from the adverse health, economic and social impacts of the disease.

- In designing interventions, international partners should ensure that communities in contested areas or territory held by EAOs are considered, so that existing perceptions of marginalization are not exacerbated.

- More broadly, international partners should conduct sustained advocacy on the need for a ceasefire and cooperation between ethnic organizations and Government entities. Despite statements proclaiming ceasefires,[10] armed conflict has continued. It is only through a collective effort in safe conditions that response actors can deliver assistance comprehensively.

- The persistence of the internet shut down in Rakhine State is and will contribute significantly to poor access to information and the likely spread of misinformation about the disease.[11] Sustained advocacy efforts on this issue are needed to lift the ban and provide communities with the information they need to address the disease.

- A rise in domestic violence was mentioned as a likely phenomenon across all states and regions. International partners should investigate innovative solutions to tackle this issue, given that movement restrictions will likely be present in Myanmar for some time, preventing more traditional modes of Sexual Gender-Based Violence (SGBV) programming.

Objective & Methodology

Research objective

The objective of this rapid assessment is to understand how parahita actors are preparing and responding to COVID-19 in at-risk areas. ‘At-risk’, in this sense, is defined by: 1) existing economic marginalization/vulnerability due to conflict; and 2) A high number of border crossings. The target sites are Rakhine (due to vulnerabilities and Bangladesh border crossing), Kayin (Thai border crossing), and Lashio (Chinese border crossings).

Key research questions

The research process was guided by answering the following research questions:

What do parahita actors see as the primary needs likely to emerge;

- How are they responding and/or planning to respond to those needs;

- How broad is their coverage in terms of geography and number of beneficiaries, including access to EAO controlled territories;

- What support do they need to be more effective: material [masks, sanitizer, etc.], information [what COVID is, how it works, how to beat it], economic [how response will affect livelihoods];

- How and to what extent do these actors and networks currently engage with formal Ministry of Health clinics and delivery systems;

- What is their willingness/ability to work across religious and ethnic lines;

- What are the current means of communication and collaboration with each other, with other CSOs, and with local and international NGOs.

Methodology

The research was designed to overcome challenges in movement restrictions and the need to produce insights in a short period of time. Given these constraints, remote key informant interviews were selected as the most appropriate tool.

The first step taken was to reach out to a consolidated network stakeholders, many of whom either run CSOs, CBOs, or parahita groups themselves. Their expert opinion on who to engage for this research provided an initial list of interview targets. Next, a snowballing methodology was deployed where further interview targets were identified during engagements with individuals on the initial target list. Further groups and individuals running response activities were subsequently sought out for further interview. In total, 15 key parahita actors and members of civil society organizations, and 2 international advisors on the Covid-19 response were interviewed for this research in April and early May 2020. In total 8 organisations from northern Shan were interviewed, 4 from Rakhine State, and 2 from Kayin State, with a further 3 interviews conducted from Yangon on the national situation.

To supplement those qualitative insights, the research team reviewed a number of key pages on social media to decipher the extent of the response in the target areas. This allowed for a greater understanding to emerge on these responses and led to the development of the maps included in this report. Relevant literature, primarily reportage from news outlets in Myanmar, were also reviewed and triangulated with the findings of from the interviews.

Limitations

This research was limited by the prevalence of armed conflict across some of the sites where these groups are based, and further limited by the need for the interview targets to respond to the disease. Given these limitations, further regional and sub-regional studies into the operations and needs of parahita networks is recommended.

Findings

Northern Shan

Context: Community needs & concerns

The primary concerns that interlocutors reported in northern Shan were around security and safety. Regular and heavy armed conflict in this region between ethnic armed groups in the Northern Alliance and the Tatmadaw has resulted in an environment where the ease of movement to avoid shelling is a crucial component of community safety. With movement restrictions imposed to curb the spread of Covid-19 in place, communities express concern that they will be caught out in bombardments. Indeed, as recently as 13 March 2020, a bombing in Muse was reported to have heightened fears again of increased armed conflict.

This sense of fear is further compounded by the upcoming rainy season. Community movement is also necessary to circumvent the disastrous effects of flooding. For the moment, quarantine zones are reportedly not robust enough to stave off the damaging effects of flooding, which is expected in the coming months.

Another major concern is the spread of the disease itself from migrant workers from China and from the Thai border. There is widely held perception among those interviewed and the communities themselves that the authorities are not adequately controlling the flow of people.

“People are still going through the borders and coming back to our villages, because border control and security are quite loose.”[12]

In terms of economic challenges, concerns are centered on the laphet (tea) farming sector. This is a major source of income to households in this region, in Palaung areas in particular, and the industry is largely suspended in an attempt to keep people at home. Many of the laborers are daily wage workers who already faced a precarious situation regarding the reliability of their livelihood.

A final key concern in communities is around information access for ethnic minority groups. Despite a claim that ‘all communities can now access the information they need in northern Shan’[13], it was found from further interviews that most Covid-19 information was translated in Burmese and Shan, and other ethnic minority language, but had not been distributed in ethnic areas to reach targets populations, especially in Pa-O and Palaung. This is crucial and will need immediate attention to ensure minority groups are not overlooked in the response and historic perceptions of marginalization and exclusion are not compounded.

Longer-term: Interviewees reported that economic impacts will be major, will grow quickly and will have long-lasting effects on the local economy. Concerns around women’s safety in the home with young, unemployed men, who were previously employed as daily wage workers in the laphet industry were also abundant. Concerns that these young men in particular would also turn more readily to drug abuse were also recorded.

Response coverage and plans

In response to these concerns, religious and parahita groups are delivering assistance to communities across northern Shan, mostly in the form of basic foods. This is being conducted in a manner akin to a humanitarian response following armed clashes. Underpinning these efforts, parahita groups are reportedly “heavily reliant”[14] on community donations, with groups such as Nam Khone parahita and individual donors offering basic foods. Other religious groups, such as the Kachin Baptist Church, are also providing mostly basic foods. However, there is a widespread concern held that the products will run out quickly, most pressingly the rice and cooking oil.

A host of other parahita groups are offering information products and sanitation material (see map above). As of the writing of this report in early May, much of their focus is on the provision of sanitation material. Interviewees reported that there are plans to pivot towards greater livelihoods support programming, though the effectiveness of cash in these areas is being questioned, given limited access to markets and disrupted supply chains, in addition to the lack of cash being donated itself. Further, there is awareness and concern in the communities around the potential inflationary effects of sudden large cash injections. These concerns are more acute in remote areas, further away from connected urban centers with markets.

Organization needs & willingness for support

Organizations reported broad and deep needs. In the short term, civil society and parahita groups will need greater provisions in terms of food, water, sanitation equipment, PPE for response groups, and information material translated to ethnic minority languages. Despite the network of actors depicted in the map above, supplies are likely to be depleted in the coming weeks, without the necessary funding streams to maintain current service levels.

“Unlike the Churches from cities, we do not have reliable funding sources”[15]

Parahita groups in this area are largely very willing to receive external support. Religious organizations operating in rural communities in particular, foresee an imminent discontinuation of their activities if other means of support cannot be found.

“We have plans to distribute PPE to public hospitals across Shan State. But it really depends on the donations and our funding sources.”[16]

Coordination with government, local and international partners

Religious organizations and parahita groups are relatively well coordinated amongst each other. For example, the Nam Khone committee constructed a quarantine zone in close coordination with the Red Cross. According to interviewed parahita group leaders, there is also an impressive level of communication between village and village-tract leaders and their communities.

There is some appetite for organizations to operate across ethnic lines, though the preferred mode of operation is to work in coordination with groups providing assistance to communities of the same ethnic background. At the same time, examples were found in northern Shan of organizations willing to work with communities of differing faiths. For instance, mirroring previous findings on Christian parahita groups operating in Rakhine State, some Christian groups are operating across religious lines. And some organizations are working across ethnic lines, for instance certain Ta’ang groups are working with ethnic Wa, Kokne, Chinese, Shan communities in their area to ensure that needs are covered.

At the regional level, international partners have also responded to Covid-19 and are primarily engaging through the Covid-19 Task Force, involving three national organizations. International partners are reporting greater challenges in responding to needs in this area due to particularly stringent Tatmadaw patrols and regulations, and corresponding difficulties in reaching smaller ethnic minority groups. At the township level, leadership for coordination is provided by the Township Medical Office (TMO). Particularly strong coordination was also recorded in Hsipaw, where a network of parahita groups are working together with at least ten CSO’s and women’s organizations.

Finally, while there is some official coordination between the Government of Myanmar and ethnic organizations in the southeast of the country, there is little in northern Shan.[17] The only cooperation found was between TMOs and the Ta’ang Health Organization and the Ta’ang Womens’ Organization.

As of 7 May 2020, it is reported that no concrete support has been sent from Naypyidaw to health clinics run by ethnic armed organisations throughout the country. On 27 April, the Government announced the creation of a committee led by Dr. Tin Myo Win, vice chair of the National Reconciliation and Peace Center, explicitly referring to close coordination with EHOs as a priority. At the time of research, however, parahita groups planning to operate in areas controlled by ethnic armed organizations reported a concern for the safety of their staff.

“It was challenging at the beginning as we felt we were in danger doing this voluntary work without anyone’s support. Those areas we worked in are under EAO administration.”[18]

Rakhine State

Context – Community needs & concerns

Both within and outside of camps, the prevalence of malnutrition, poverty, pre-existing health conditions and a lower access to healthcare facilities than in other parts of Myanmar, mean that communities that reside in Rakhine are generally at high risk of the disease.[19] The ongoing armed conflict between the Arakan Army and the Tatmadaw compound these vulnerabilities. From the interviews conducted, the State’s division into two areas with contrasting needs remains salient: 1) a better-connected and better-prepared south (Thandwe and below) and 2) the central and northern townships, where needs for both displaced Rakhine and disenfranchised Muslim groups are greater, in addition to existing vulnerabilities outside of the camps.

Interviewees who were predominantly ethnic Rakhine emphasized the humanitarian needs for displaced Rakhine as being of primary concern, arguing that those groups had been overlooked by both the Union-level Government and by the international community. In these IDP camps, the interviewees highlighted that the lack of basic infrastructure – such as the water drainage infrastructure needed for washing hands – in addition to a lack of space means that this population group is highly vulnerable to the disease. In camps for the Rohingya, health outcomes are also notably worse than those outside of camps; for instance, a study by an INGO in Rakhine stated the incidence of tuberculosis as nine times higher in those camps than in nearby villages.[20]

In northern Rakhine State, concerns regarding the virus crossing from Bangladesh are also high. Communities in the north of the state have reported concerns about the virus crossing the border through formal or informal border crossings. Small numbers of Rohingya have been to reported to return informally to Rakhine State up to late April,[21] while armed groups continue to operate on both sides of the border. The further stigmatization of the Rohingya communities under these conditions is a risk – Rohingya in Rakhine State may be associated with any spread of the virus. Following the identification of the first cases of the virus in the mega-camps in Bangladesh on 14 May, one vocal Rakhine politician took to social media to warn officials against taking bribes to allow Rohingya to enter Myanmar, and Myanmar announced that it would raise security along the border with Bangladesh to prevent the spread of the virus.[22]

Information access is poorer due to blockages of internet and mobile access, resulting in a lower level of reported awareness on the disease than in other parts of the country.[23] Representatives of parahita groups interviewed argued that Rakhine’s population would struggle to adhere to the social distancing guidance while also being primarily occupied by the armed conflict.

“A mobile internet shutdown has really left displaced communities in Rakhine vulnerable to a Covid-19 virus outbreak. They can’t pay attention to the virus outbreak while they worry about wars.”[24]

Safety is a widespread concern here. The killing by gunfire of a WHO staff member on April 20 has reemphasized the deteriorating security conditions and the risks that response actors face in providing assistance.

Longer term: Concerns are rising over the lack of PPE for hospitals – and a watchgroup ‘Rakhine Covid-19 Watch Group’ has been created as a result to connect suppliers with community organizations that are able to deliver the PPE to medical centers. More broadly, communities in Rakhine are aware of the State’s poverty and higher proportion of daily wage workers meaning that it is more vulnerable to an economic downturn.

Response coverage and plans

Due to government restrictions largely but not exclusively on international assistance providers since 2016, informal groups in Rakhine have increasingly become the first-responders with front-line staff in Rakhine State. National CSOs and CBOs are in general, well-coordinated through a regional mechanism. Local organisations, such as Green network, for instance, is distributing food assistance while also raising awareness by disseminating guidance on Covid-19 response in urban Sittwe. Much of the response, though, is stretched to full capacity.[25]

Although religious institutions are not as active in Rakhine compared to urban centers in other states across Myanmar, some are providing assistance. For instance in Ponnagyun, a religious figure is working with local youth groups to conduct awareness raising alongside food distribution to IDP camps in Myebon. However, the phenomenon of transforming religious sites – including monasteries, churches, mosques and temples – to quarantine zones has not been as widespread. In large part, the decision not to open religious centers has been taken as a precautionary step to protect senior clergy members, many of whom reside in their centers. With similar reasoning, Hindu community leaders that were interviewed reported that they were providing basic food supplies to Hindu communities, but had cancelled all religious events at temples and were urging community members to stay home and follow the Ministry of Health and Sport’s guidelines.

Certain CSOs have also mobilized to tackle the issue of misinformation. In Rakhine State, where misinformation is rife,[26] the prevalence of rumors around Covid-19 was highlighted as a key issue. The Rakhine Covid-19 Watch Group has created a Facebook page designed to tackle this issue and provide accurate information and advisory services for people in Rakhine. The watch group is exploring FM radio and other information channels, including a smartphone application, to offer different ways in which this information can be disseminated.[27]

Organization needs & willingness for support

Organizations interviewed for this research expressed very high levels of openness to receiving support from international partners in Rakhine. The support requested ranged from information and advisory products, to basic food and water, to medical equipment including PPE, to longer term livelihoods support. It is worth noting here that many organizations have been calling for greater assistance to people displaced by armed conflict for some time, prior to the onset of the disease. They argue that such an oversight is yet another symptom of the Government de-prioritizing the needs of those displaced in ethnic areas, including in Rakhine State.

Rakhine, in contrast to the other regions examined in this report, has not developed an ethnic health system, leaving the Government’s network of medical offices and primary healthcare centers particularly exposed. Sittwe General Hospital is chronically underfunded, where 4% of all admitted patients die – in many cases due to staffing shortages.[28]

The corresponding reliance on donations from communities and indeed from the private sector appears to be high. For instance, in Sittwe, a company donated a ventilator machine to the public hospital in April 2020. Other health facilities at the township levels are also of a particularly low standard when compared to other states/regions in Myanmar. Given these challenges, the burden on parahita groups and CSOs working in tandem with international partners is likely to be significant.

“Getting information on healthcare is lacking for so many reasons. [One is that] there is really limited human resources from township health department/clinics.”[29]

Coordination with government, local and international partners

Coordination within IDP camps is fairly strong with ‘watch groups’ established that are responsible for case identification and management. Coordination processes with the government for referrals have also been established, though are reportedly in need of improvement. Further, there is usually good coordination with Township Medical Offices (TMOs) and various other Government actors at the township level, including with Task Forces established by the GAD. In addition, the Ministry of Social Welfare, Relief and Resettlement have also launched response teams to the camps. [30]These coordination structures largely started functioning in April, several weeks after local groups had been responding to needs.

At the state level, coordination amongst Rakhine groups is relatively strong with formation of the Arakan Humanitarian Coordination Team (AHCT), a forum of six CSOs and parahita groups. The team have also stated a willingness to work across religious and ethnic groups. These groups are predominantly operational across central and northern Rakhine (as per the map above) and are delivering critical services across multiple townships.

“Our community-based responses, along with CSO’s and CBO’s, are filling the gaps of the Government’s response to Covid.”[31]

Coordination with INGOs continues through existing channels in the Rakhine State Government’s Coordination Committee (CC), though is hampered by cumbersome processes to obtain permissions.

Kayin State

Context – Community needs & concerns:

In Kayin, community concerns converge on the large numbers of returning migrant workers from Thailand and their potential to transmit the disease. Despite the establishment of quarantine centers, those interviewed for this research stated that compliance with the need to quarantine is extremely low. The conditions of the quarantine centers themselves are reportedly contributing to this.

“I have heard that about 5,000 homecoming migrant workers will be coming back to this area. Kayin state will be hosting all those returnees.”[32]

Concerns about the need to raise awareness on the importance of quarantine and the need to practice social distancing were also predominant in the thinking of the parahita groups interviewed. They stated that many community members are still unaware of the need to wash hands and practice distancing, not just amongst those returning from work in Thailand. Linked to this was a lack of information in ethnic minority languages. As much of northern Kayin is a mixed-language area, information and guidance requires translation beyond Burmese and Kayin languages for communities to understand the material and adopt practices.

Parahita groups also reported extremely high prices of PPE and sanitation equipment, stating that their networks of donors are unlikely to be able to meet the PPE requirements needed for the population at risk. Groups also identified that March-May is usually the time that children would be taken to hospitals to have their vaccines. This has largely not occurred this year due to fears of contracting the virus, thus leaving the children more vulnerable to a host of other viruses and diseases.

Finally, concerns around the Tatmadaw’s offensives in northern Kayin State are also worrying for communities. In February 2020, a military offensive in northern Kayin State led to the destruction of multiple villages. In response, the Karen Peace Support Network (KPSN) issued a statement outlining that communities there are “more afraid of the army than they are of Covid-19.’[33]

Longer term: The parahita groups interviewed highlighted the longer-term risk of women as foreseeable victims of domestic violence, given the restrictions placed on the ability to work. Further, there are concerns with growing unemployment and inadequate food supplies, which may lead to social unrest. Finally, concerns were also recorded around the potential for renewed violence between the tatmadaw and militias in northern Kayin State, who may seek opportunities to do so while media attention is diverted to covering the spread of the disease.

Response coverage and plans

The focus for response actors in this initial phase has been in the distribution of PPE across the State. A multi-stakeholder operation, including some limited degree of cooperation between Government and ethnic health organizations, has been operating to distribute the equipment. For parahita groups, large donations from individual donors and community members are fueling a significant response from a variety of organizations. However, the extent of the parahita group mobilization also puts those volunteers at risk of being potential vectors of the disease.[34]

“Some donors seem a bit reluctant to come to quarantine centers by themselves. Therefore, parahita groups are the ones who voluntarily are helping out with their own hands for the needs of community quarantine centers.”[35]

In Kayin, religious institutions have more readily been transformed into quarantine zones for returning migrants than in the other regions examined. In Hpa-an, for instance, Mogok Vipassana meditation center was vacated of all monks previously residing there due to the closure of its summer operations, and due it being turned into a quarantine zone. Its location outside of Hpa-an, away from its urban center, was also a contributing factor as to why it was selected.

At the same time, the Government’s restrictions on Ma Ba Tha / Buddha Dhamma Parahita Foundation activities, combined with a very effective Facebook ban, has limited the organisation’s monastic and laypersons network of welfare providers from functioning with the same coverage and efficacy as before. Communities that are usually reliant on these networks, for instance, in parts of rural Kayin and urban Sittwe where rainy season flooding is common, are thus likely to experience unmet needs due to the shortfall in services. Ma Ba Tha / Buddha Dhamma Parahita Foundation have in prior instances provided rice, cooking oil, and cash support (among other services) to Buddhist communities affected by natural disasters.

Organization needs & willingness for support

The first priority that parahita groups stated was greater information. Groups remain concerned in Kayin State that public awareness of the measures designed to protect community safety is low. More specific information products are also needed, for instance to signpost quarantine centers.

Similar to other states and regions examined, parahita groups interviewed here requested a range of support from international partners. The urgency of the needs is clear. As of 29 April, a member of a camp management committee in Hlaingbwe township which hosts more than 5,000 IDPs reported to a news outlet that “we have enough rice for 20 days…we have received no indication yet as to whether the government or other donors plan to provide us with any more.”[36] In another example, a catholic church was converted to a quarantine center with the expectation that Government departments would provide services and sanitation equipment. However, that support never arrived, leaving a civil society organization to fill the infrastructure gaps.[37]

Only some parahita groups reported having links to CSOs that are being funded by international response actors, and are being trained by organizations such as the Local Resource Center (LRC) on how to access larger funds. However, the groups interviewed stated that the process is generally slow and cumbersome, and underlined the need for quicker and more flexible funding to be made available. As of the writing of this report, some farmers have begun returning to work while practicing social distancing. To support these efforts, groups interviewed requested international partners to concentrate on supporting farmers with seeds and extension services to aid the recovery of local agriculture.

Coordination with government, local and international partners

In Kayin State, interviewees reflected on a relatively higher level of coordination among different parahita groups, CSOs and the Government, compared to the other regions examined. At the township level, greater leadership roles were assigned to TMOs and RHCs, including in ethnic areas. Coordination with organizations operating in ethnic areas also seems to be taking place.

At the same time, interviewees were quick to state that they would be very willing to cooperate with organizations working in communities of different ethnic backgrounds. They would go on to state that these communities of a different ethnic background would be better served by organizations from that community itself.

“We do not actively work in most of the ethnic armed controlled areas as there are some organizations that are specifically working in those areas.”[38]

Indeed, regional networks and partnerships between faith-based and civil society organizations seem extensive in Kayin. For instance, the Myanmar Catholic Church Response to Covid-19’ includes four civil society and faith-based organisations that report to a steering committee of Patron Bishops. The network has, as of 30 April 2020, reached 237,668 individuals with a combination of in-kind, sanitation, and care for disabled persons across northern Kayin, Shan and Kachin. This network is also coordinating with the Ministry of Health and Sports and the Department of Social Welfare, in Myanmar, and the Dicastery for Promoting Integral Human Development in the Vatican.[39]

At the state level, GAD and the State Agricultural Institute are involved in coordination, alongside the police for enforcing social distancing measures. In terms of coordination, interviewees stated that there is still room for improvement as rural health centers (RHCs) need to be better linked to the state government and the MoHS.

The groups interviewed did not report significant coordination with international partners and health clinics run by EAO’s during the research. As of 7 May, local observers also stated that the coordination between ethnic organisations and the Government in this region is reportedly “minimal”.[40]

[1] Centre for Mathematical Modelling of Infectious Diseases, ‘How many are at risk of severe Covid-19 disease? Rapid global, regional and national estimates for 2020’, (14 April 2020): https://cmmid.github.io/topics/covid19/Global_risk_factors.html

[2] ONOW Myanmar, ‘Early Employment Impacts of Covid-19 in Myanmar’, (April 2020): https://medium.com/opportunities-now-myanmar/early-employment-impacts-of-covid-19-in-myanmar-7ca3c500da00

[3] The Irrawaddy, ‘Myanmar to Receive $2bn in Covid-19 relief from international development organisations’, (11 May 2020): https://www.irrawaddy.com/specials/myanmar-covid-19/myanmar-receive-2b-covid-19-relief-intl-development-organizations.html

[4] Myanmar Times, ‘Domestic Violence Rises in Myanmar During Community Lockdown’, (1 April 2020): https://www.mmtimes.com/news/domestic-violence-rises-myanmar-during-community-lockdown.html

[5] Social Sciences in Humanitarian Action, ‘Key considerations: Covid-19 in the context of conflict and displacement in Myanmar’, (May 2020): https://opendocs.ids.ac.uk/opendocs/bitstream/handle/20.500.12413/15295/SSHAP%20COVID-19%20Key%20Considerations%20Myanmar.pdf?sequence=5&isAllowed=y

[6] Social Sciences in Humanitarian Action, ‘Key considerations: Covid-19 in the context of conflict and displacement in Myanmar’, (May 2020): https://opendocs.ids.ac.uk/opendocs/bitstream/handle/20.500.12413/15295/SSHAP%20COVID-19%20Key%20Considerations%20Myanmar.pdf?sequence=5&isAllowed=y

[7] BBC World News, ‘Coronavirus: WHO worker killed in Myanmar collecting samples’, (April 2020): https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-asia-52366811

[8] Medecin Sans Frontiere, ‘Crisis Update 2020’, (April 2020): https://www.msf.org/drc-ebola-outbreak-crisis-update

[9] World Bank, ‘Socioeconomic Report: Myanmar Living Conditions Survey’, (February 2020): https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/myanmar/publication/socio-economic-report-myanmar-living-conditions-survey

[10] https://vk.com/arakanarmyinfodesk?z=photo-185406812_457239162%2Fwall-171407235_4051

[11] The Lowy Institute, ‘Under cover of Covid-19, conflict in Myanmar goes unchecked’, (8 May 2020): https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/under-cover-covid-19-conflict-myanmar-goes-unchecked

[12] Interview with parahita group, northern Shan state, April 2020

[13] Interview with INGO staff member, northern Shan state, April 2020

[14] Interview with parahita group, northern Shan state, April 2020

[15] Interview with parahita group, northern Shan state, April 2020

[16] Interview with CSO, northern Shan state, April 2020

[17] Frontier Myanmar, ‘Govt and ethnic armed groups must build bridges to beat Covid-19’, (7 May 2020): https://frontiermyanmar.net/en/govt-and-ethnic-armed-groups-must-build-bridges-to-beat-covid-19?fbclid=IwAR39Bucn1QbRJrzC_pqIWkuCUkQIfeqSuSz1XMGyNH9eRXmS5DB5XOej_aI

[18] Interview with parahita group, northern Shan state, April 2020

[19] The World Bank, ‘Myanmar Covid-19 Emergency Response Project’, (April 2020): http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/178971586428026889/pdf/Project-Information-Document-Myanmar-COVID-19-Emergency-Response-Project-P173902.pdf

[20] International Rescue Committee, ‘Poor Shelter Conditions: Threats to Health, Dignity & Safety’, (2017): https://www.rescue.org/sites/default/files/document/1664/ircsittweshelterbriefupdated.pdf

[21] Democratic Voice of Burma, ‘Four Bengalis Again Enter Myanmar from Bangladesh’ (2 May 2020): http://burmese.dvb.no/archives/385505?fbclid=IwAR2FVGYwTv4nFvZ9VRWba_-Z7xpgy0Hkpxlq117UMXpsUaF9pSOQvRfBT_Q.

[22] Democratic Voice of Burma, ‘Security Raised at Maungdaw Border to Stop Illegal Entry’ (17 May 2020): http://burmese.dvb.no/archives/388537?fbclid=IwAR3nvFngro10hFMsULTbn2tg8NKz14eLSUN5u5faTuwG62Raqu7oudGzjh0

[23] Interview with CSO, Sittwe, Rakhine, April 2020

[24] Interview with CSO, Sittwe, Rakhine, April 2020

[25] Interview with CSO, Sittwe, Rakhine, April 2020

[26] Reuters, ‘Flying News: Humanitarian media counter Rohingya rumors’, Jared Ferrie (26 September 2018): https://www.reuters.com/article/us-bangladesh-refugees-rohingya-media/flying-news-humanitarian-media-counter-rohingya-refugee-rumors-idUSKCN1M60L6

[27] Interview with CSO, Sittwe, Rakhine, April 2020

[28] BNI Multimedia Group, ‘Four percent of patients die due to staff shortages in Sittwe hospital’, (18 October 2018): https://www.bnionline.net/en/news/four-percent-patients-die-due-staff-shortage-sittwe-hospital

[29] Interview with CSO, Sittwe, Rakhine, April 2020

[30] The Diplomat, ‘Myanmar and Covid-19’, (1 May 2020): https://thediplomat.com/2020/05/myanmar-and-covid-19/

[31] Interview with CSO, Sittwe, Rakhine, April 2020

[32] Interview with CSO, Hpa-an, Kayin State, April 2020

[33] DW, ‘Myanmar: Armed conflicts puts brakes on Covid-response’, April 2020: https://www.dw.com/en/myanmar-armed-conflict-puts-brakes-on-covid-19-response/a-53360164

[34] Interview with CSO, Hpa-an, Kayin State, April 2020

[35] Interview with CSO, Hpa-an, Kayin State, April 2020

[36] Frontier Myanmar, ‘IDPs being left behind in the response to Covid-19, say relief workers’, (11 May 2020): https://frontiermyanmar.net/en/idps-being-left-behind-in-the-response-to-covid-19-say-relief-workers

[37] Interview with CSO, Loikaw, Shan State, May 2020

[38] Interview with CSO, Hpa-an, Kayin State, April 2020

[39] Interview with CSO, Loikaw, Shan State, May 2020

[40] Frontier Myanmar, ‘Govt and ethnic armed groups must build bridges to beat Covid-19’, (7 May 2020): https://frontiermyanmar.net/en/govt-and-ethnic-armed-groups-must-build-bridges-to-beat-covid-19?fbclid=IwAR39Bucn1QbRJrzC_pqIWkuCUkQIfeqSuSz1XMGyNH9eRXmS5DB5XOej_aI