Executive Summary

The Myanmar military’s 1 February seizure of power will have significant and long lasting implications for the Myanmar humanitarian response in Kachin State and across Myanmar. Security forces throughout the country have waged a violent campaign against the anti-coup protest movement, which has mobilised in most parts of the country. The military faces growing international condemnation and isolation as it suppresses basic rights and escalates bans on independent media, mass arrests of civil society actors, targeting of humanitarian responders with armed violence, and the use of military-grade weapons against communities in both urban and rural residential areas— killing over 750 people and detaining over 3,500 others to date.[1] The country’s economy is rapidly collapsing in the face of a widespread civil disobedience movement while Western investors flee or are forced by the junta to suspend and rethink operations. In northern Myanmar’s Kachin State, armed clashes between the Tatmadaw and the Kachin Independence Army (KIA) are again escalating. New displacement has already exceeded 2,000 people, and humanitarian agencies are responding under difficult circumstances.

This scenario planning exercise is designed to support humanitarian response actors with forward-looking planning. While many scenarios are possible in Kachin State, three broad scenarios are presented here: the return to a low-intensity armed conflict; a ceasefire agreement involving the Tatmadaw and the KIA; and an aggressive escalation of armed conflict. It should not be expected that any of the scenarios presented here will emerge exactly as described — the reality will likely combine elements of all three. The value of the scenario planning exercise is in identifying emerging challenges and potential flashpoints for communities and the response.

There are certain key challenges likely to emerge under any scenario. There is an imperative to avoid the Tatmadaw’s financial systems. Restrictions and economic instability means the Myanmar banking system will no longer be a viable means of making financial transactions for humanitarian responders. International organisations will need to avoid legitimising the Tatmadaw’s State Administration Council (SAC) and its brutal crackdown. This will need to be taken into account in the pursuit of operations permissions and transparency will become paramount in all interactions with line ministries. Tatmadaw restrictions will drive civil society organisations underground in government-controlled areas, necessitating these CSOs to move their operational base to areas under the control of the Kachin Independence Organisation and its armed wing the Kachin Independence Army (KIO/A), and to China’s Yunnan Province for infrastructure and low-visibility procurement.

Humanitarian needs are rapidly rising as the KIO/A and the Tatmadaw again engage in an escalating armed conflict in Kachin State. The shutdown of the financial system and current cash withdrawal limitations already pose serious impediments to humanitarian action, while local and national partner organisations face increased pressure from the Tatmadaw. New, flexible and innovative approaches will be necessary to reach affected communities, and success will hinge in large part on strong local partnerships and low visibility.

Recommendations to Response Actors

Whichever scenario eventuates in Kachin State, humanitarian responders must undertake a dramatic shift in their operational strategies. Cities in government-controlled areas will no longer be viable as sole operational gateways to Kachin’s crisis-affected communities. Operators should immediately begin working with local partners to develop low-visibility strategies to:

- establish long-term bases for humanitarian response operations within KIO/A areas;

- pre-position resources necessary for an emergency response — with a particular focus on food, medical materials, and medical personnel — and work with appropriate stakeholders to identify and secure multiple procurement and transport strategies for future supplies;

- build increased trust and support among ethnic Kachin counterparts in Yunnan Province to strengthen informal support and local security for response activities;

- set up new or additional Chinese bank accounts to navigate forthcoming financial challenges.

Background

On 1 February 2021, the Myanmar armed forces (Tatmadaw) staged a coup d’etat and seized control of the state. In rationalising this coup, the military has cited State of Emergency provisions of the 2008 Constitution, which allow the armed forces to take power under certain circumstances, but legal experts argue that these conditions were absent and that the Tatmadaw is in breach of the constitution.[2]

In reaction to the coup, people across the vast majority of Myanmar have mobilised demonstrations and a potent civil disobedience movement (CDM), designed to shut down the economy and impact the Tatmadaw’s ability to govern. From late February, the Tatmadaw adopted an increasingly violent approach to suppress dissent. As of 3 May, the Assistance Association for Political Prisoners reports that 766 demonstrators and bystanders have been killed and 3,614 remain in detention on the basis of suspected opposition to the coup.[3]

In Kachin State, Myanmar’s northernmost state, the Tatmadaw has presented a fierce show of force since 1 February. While police were initially deployed to the streets of many towns and cities across the country, military personnel confronted people in the Kachin State capital Myitkyina and other areas of the state. As elsewhere in the country, protests have been met by military atrocities. On 8 March, the Tatmadaw shot and killed two protesters in Myitkyina.

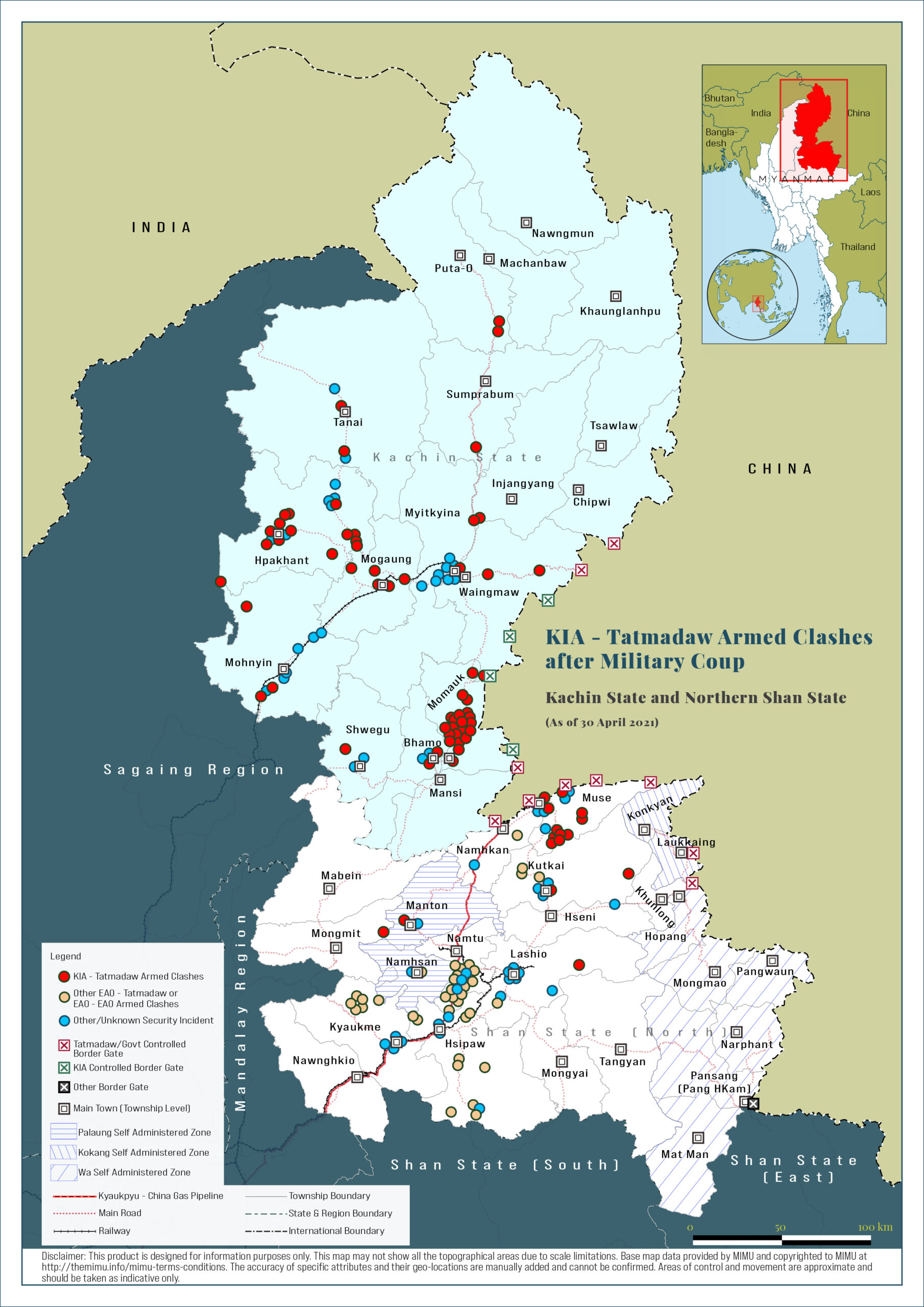

The Kachin Independence Organisation and its armed wing the Kachin Independence Army (KIO/A) responded with new attacks against the Tatmadaw on 11 March — carrying out a prior commitment to respond should the military harm civilians. This marked an end to the fragile reprieve in armed clashes that had prevailed in Kachin State since mid-2018. Fighting has rapidly escalated, including clashes on 24 March near the Chinese border during which the KIA seized a Tatmadaw base; a fierce contest for control of this base has been playing out since. The Tatmadaw is reinforcing troops, shelling near KIA bases and IDP sites, and blocking commodity transportation routes to KIO/A areas — an established Tatmadaw tactic in active conflict zones. More than 2,000 people have now been displaced.

Frequent armed confrontations between the Tatmadaw and the KIA are being reported across Kachin State, from Hpakant to Tanai, Injanyang, Kamaing, Mogaung, Namti, Puta-O, Sadaung, Sein Lum, Sumprabum, Waingmaw, and Shwegu townships and sub-townships. In Tanai Township, the KIA torched a building and vehicles belonging to Yuzana Company – known for its close ties with senior regime and former military leaders. On 28 March, it was reported that the KIA had attacked and killed over 30 Myanmar security forces who had taken refuge inside jade mines. The KIA has warned of retaliation in urban areas if security forces continue to harm anti-coup demonstrators. The KIO is embracing the CDM, providing demonstrators with basic military training and inviting Myanmar military members to join the KIA if they do not wish to serve the junta.

However, as was the case for many armed ethnic organisations, the KIO/A’s relationship with Aung San Suu Kyi and her National League for Democracy (NLD) had been difficult between 2016 and 2021. Its position on the legitimacy of the Committee Representing Pyidaungsu Hluttaw (CRPH) and the National Unity Government (established in April 2021 as a rival to the Tatamdaw’s regime) is unclear. The CRPH is calling for ethnic armed groups across Myanmar to join together in a federal army to oppose the Tatmadaw’s State Administration Council (SAC), but the KIA has yet to declare any position. To represent Kachin political aspirations, international and domestic Kachin organizations have formed a new coordination and leadership body, the Kachin Political Interim Coordination Team (KPICT). The KPICT is in regular consultation with the CPRH, and says it is working towards mutual political interests: to end authoritarianism and promulgate a genuine federal union.

Finally, any scenario planning in Myanmar needs to consider the role of China, Myanmar’s powerful neighbour. A myriad of Chinese state and non-state actors hold economic and political interests in Kachin State and across Myanmar. China seeks stability on its border more than anything else; it is concerned about the movement of refugees, and the political and economic implications of developments in Myanmar. On 30 March, Chinese authorities closed the Ruili and Jiegao border crossings,[4] signalling that any cross-border humanitarian response will face restrictions. The KIO/A’s rejection of Beijing’s pressure not to escalate clashes means further fighting on the border should be expected. China and its representatives in Myanmar have also sent mixed messages about the situation in the country, complicating arguments that they will back Myanmar’s military unconditionally.[5] The ambassador to Myanmar has publicly spoken of China’s displeasure with the situation in Myanmar,[6] and has made contact with the CRPH.[7] However, Beijing has also provided the Tatmadaw with support to consolidate control over telecommunications in the country. China is increasing its military presence on its Myanmar border[8] and preventing cross-border aid, but Yunnan authorities have not always fallen into step with Beijing’s orders. After the ceasefire in Kachin State broke down in 2013, for example, local authorities showed flexibility in allowing a low-visibility response from its territory.

Scenarios

To assist donors and humanitarian response actors in forward-looking planning, three scenarios are presented here, describing the most likely contextual trajectories over the next six months in Kachin State, with a focus on implications for the response. Given the unpredictability and dynamism of the current situation across Myanmar, these scenarios should be taken as indicative. It is unlikely that any one scenario will emerge completely as described here — over the months to come it is likely that elements of all three will appear. Armed conflict escalation, at least in the short term, should be assumed in each scenario, with negative impacts for both communities and response actors.

Scenario 1

Return to Low-Intensity Armed Conflict

This scenario sees a stabilisation of the current intensity of armed clashes between the KIA and the Tatmadaw across Kachin State. No major territorial gains (or losses) are made by either party. Most of the fighting remains limited to rural areas, while urban areas are largely untouched. Militarisation increases in all areas and the space for civil society narrows, as the Tatmadaw uses violence and coercion to crush demonstrations, the CDM movement, and other resistance. The halt of state services, especially internet connection, is used as a tool to disrupt opposition and impair communication. The Peacetalks Creation Group (PCG), inactive in recent years amid limited KIO/A-Tatmadaw negotiations, renews its involvement in maintaining dialogue as tensions escalate. With an interest in protecting stability and its political and economic influence, China may also play a role in mediating dialogue, or in pressuring actors into negotiations.

Impact for Communities

- Temporary and elastic displacement in rural areas is highly likely, with IDPs staying in displacement sites but regularly returning to their places of origin to secure property or engage in livelihoods.

- Displacement from urban, or peri-urban, areas is limited, as clashes remain concentrated in rural locations, but IDPs are likely to continue arriving in urban areas.

- The economy suffers but is not fully compromised. Vulnerable populations require livelihood support following the impacts of COVID-19 and the instability sparked by the 1 February coup.

Impact for the Response

- Visible collaboration with local and national organisations becomes increasingly difficult, as the Tatmadaw has reduced the space for civil society nationwide. Civil society groups in ethnic areas are treated with particular suspicion due to their presumed relationships with ethnic armed organisations.

- As needs rise inside non-government-controlled areas, support will be needed for civil society organisations operating in KIO/A territory. This support will involve cross-border or remote modalities, and CSOs have significant capacities in this regard. Donors will have to adjust to new modalities of aid delivery to fit the new context. This will require a revision of financial and reporting mechanisms; models can be drawn from other contexts.

- Agencies will have to negotiate access with both the Tatmadaw and the KIO, calibrating their efforts in this regard to the specific location of activities. This will involve an often delicate balance, and agencies will have to tread carefully to ensure KIO/A authorities regard them as neutral and impartial. Long suspicious of international humanitarian agencies, the Tatmadaw may ban their presence entirely in response to their perceived support for the ‘terrorist’ resistance in Kachin State or elsewhere in Myanmar. With little chance of convincing Tatmadaw authorities of their neutrality, and little flexibility to collaborate with the SAC in light of its brutal assault on Myanmar civilians, international agencies will likely have to reduce the visibility of their presence and operations in government-controlled Kachin State. Some may be expelled entirely from government-controlled areas of Myanmar.

- Cross-border and remote modalities will require innovative approaches to money transfers. This might involve informal money transfer mechanisms, such as Hundi networks, and the use of Chinese banks, which many responders in non-government-controlled areas are already using. China may oppose these efforts, so any cross-border transactions should be carefully monitored.

- The return and resettlement process will result in some camp closures in government-controlled areas, where there is a risk of involuntary returns. However, most camps will remain operational, as a result of realities on the ground: increased displacement, inconducive conditions for returns, and no real incentive for the Tatmadaw to prioritise the process.

- Security concerns for all responders will rise as a result of increased militarisation, and growing numbers of checkpoints.

Crowds protest the military coup in Myitkyina. Image: Khun Ring 2021

Scenario 2

Ceasefire Agreement

In this scenario, the Tatmadaw and KIO/A negotiate a political settlement, following limited armed clashes. This may be a bilateral ceasefire, a “bloc ceasefire” including KIO allies, or a deal as part of the Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement (NCA) or a new peace process paradigm. Across the nation, the Tatmadaw maintains its increasingly authoritarian approach to governance, threatening civil liberties and the capacities of national actors to operate freely.

There are significant barriers to a ceasefire, however. Armed clashes in Kachin State appear set on a trajectory of escalation, and sources report that the prospects for any ceasefire are low. Recent history is also instructive in this regard. The KIO/A chose not to sign on to the NCA, nor any other ceasefire deal, since the resumption of the Kachin conflict in 2011. However, the Tatmadaw’s 1994 ceasefire with the KIO/A was instrumental in enabling it to scale down its presence in northern Myanmar in order to launch the massive southeastern offensive that toppled the headquarters of the Karen National Union, drove the pro-democracy shadow government out of Myanmar, and generated a refugee crisis in which thousands fled Karen areas for Thailand.

If the Tatmadaw were to present a similar agreement to KIO/A in 2021, three key factors could dissuade the KIO/A from signing: (1) the Tatmadaw’s violation of the previous agreement in 2011, as KIO/A are looking for more substantial guarantees of lasting control and now face an even greater trust deficit with respect to the potential longevity of any Tatmadaw deal; (2) KIO/A desire to avoid disrupting ethnic unity and perceived progress towards its long-term aim of Kachin autonomy within a functioning federal democracy by contributing to the possibility of another large-scale Tatmadaw offensive in the southeast; (3) increased visibility of Kachin developments due to nationwide information sharing across social media and the consequent risk that KIO/A and/or the Kachin community more broadly could be deemed traitors to the Spring Revolution and targeted by social media campaigns. If a Tatmadaw ceasefire offer were substantial enough, however, these barriers could be overcome.

Impact for Communities

- The Kachin State economy, along with the national economy, suffers but is not fully compromised. Vulnerable populations require livelihood support following the impacts of COVID-19 and the instability sparked by the 1 February coup.

- Some new displacement in the short term, but numbers stabilise in the medium to long term.

Impact for the Response

- National dynamics surrounding Tatmadaw abuses and governance will mean that access for international responders is increasingly limited. The humanitarian response will continue to rely on national and local partners, but remote and cross-border approaches will also have to be prioritised.

- While the return and resettlement process continues, humanitarian actors will have little visibility on the camp closure process due to nationwide dynamics preventing access. The threat of forced returns, particularly in government-controlled areas, is high. China remains capable of increasing its involvement in the return and resettlement process, and transparency and consultations remain issues of concern.

- Agencies will continue to have to negotiate access with both the Tatmadaw and the KIO; these negotiations must be specific to where their activities are taking place, and agencies must take care to present their work as neutral and impartial. Long suspicious of international humanitarian agencies, the Tatmadaw may ban their presence entirely in response to their perceived support for the ‘terrorist’ resistance in Kachin State or elsewhere in Myanmar. With little chance of convincing Tatmadaw authorities of their neutrality, and little flexibility to collaborate with the SAC in light of its brutal assault on Myanmar civilians, international agencies will likely have to reduce the visibility of their presence and operations in government-controlled Kachin State. Some may be expelled entirely from government-controlled areas of Myanmar.

- Cross border and remote modalities will require innovative approaches to money transfers. This might involve informal money transfer mechanisms, such as Hundi networks, or the use of Chinese banks, which many agencies in non-government-controlled areas are already using.

- Security concerns for all responders rise as a result of increased militarisation and growing numbers of checkpoints.

Scenario 3

Aggressive Escalation of Armed Conflict

This scenario sees a rapid and intense escalation of armed clashes. Either the Tatmadaw or the KIO/A may lead this escalation. Territorial gains are made by armed actors and conflict-affected areas of the state are increasingly militarised by the KIA, the Tatmadaw, and other militia groups seeking to control territory, access to resources, and service provision. As polarisation increasingly takes hold, it is very difficult for the PCG to engage in negotiations. One variation of this scenario involves the KIO/A joining other armed ethnic organisations in some form of “federal army” to confront the Tatmadaw, but such unity is certainly not guaranteed.

China may try to intervene to protect its own political and economic interests, but it is not clear if it has sufficient influence to bring Kachin State back to its status quo of uneasy peace. Perceptions that China is backing the Tatmadaw may lead demonstrators to target Chinese investments or nationals in Kachin State.[9] This would likely encourage China to back the Tatmadaw. If China feels its interests are existentially threatened in Kachin State, it will likely exert pressure on the KIO/A, Kachin displaced persons and migrants in Yunnan Province, and Kachin CSO actors dependent on access to Yunnan. This may be achieved by seizing and freezing Kachin accounts in Chinese banks, pushing persons displaced into China back to Myanmar and increasing the harassment of migrants, or detaining KIO/A officials in a show of its dwindling tolerance. If Yunnan authorities cooperate with Beijing, such a crackdown will be intensified, to include increased military patrols and restricted access to known unofficial border crossings and smuggling routes. As this could hurt the interests of the Yunnan elite, it would require successful lobbying by Beijing in Yunnan. If Yunnan authorities are unwilling to cooperate, Beijing would likely publicly summon one or more prominent officials to Beijing, in order to send the message that cooperation is mandatory. Beijing may further consider sending a more dramatic message to the KIO/A by activating the additional troops it has moved to Yunnan Province and targeting KIA bases — or even staging a limited military incursion into Myanmar.

In a worst-case form of this scenario, armed clashes occur in heavily populated urban areas, prompting severe protection risks for communities and new logistical challenges for humanitarian responders. There is the potential for urban-based violent resistance in locations such as Bhamo, Hpakant, Mohnyin and Myitkyina townships. Armed clashes in locations such as these risks paralysing any response from within Myanmar.

The onset of the monsoon season in June makes movement more challenging for all actors, prompting a reduction in the intensity of the fighting. This may present an opportunity for negotiations, likely backed by China, which wishes to restore some level of stability.

Impact for Communities

- Adverse impacts for IDPs will be serious and widespread, likely driving many to seek refuge in KIO areas, even when doing so entails difficult, higher risk journeys. The consequent trend of greatly deteriorating medical conditions among new IDP arrivals in KIO areas will present a healthcare crisis the KIO/A is not equipped to address.

- Rural displacement increases rapidly and significantly, both internally and cross-border into China. Displacement among urban communities is also likely given displacement patterns since 2011, depending on the trajectory of armed clashes.

- Landmine use increases, causing large numbers of civilian casualties and preventing the return of IDPs either temporarily or longer term.

- Voluntary recruitment to the KIA increases substantially, greatly escalating the risk of its recruitment of children. Tatmadaw practices of forced labour, especially portering, become widespread to sustain military activities.

- Economic activity is devastated. The financial system is completely compromised. Inbound migrant workers from Rakhine and the dry zone either return to their places of origin or flee elsewhere, with implications for local economies in their home towns and villages. Access to markets is impaired and both formal and informal economic activities are disrupted by frequent clashes.

- Services, such as electricity, internet, and telecommunications, are suspended by the SAC or disrupted by the CDM. Some are replaced by KIO and cross-border alternatives, but significant gaps remain.

Impact for the Response

- Following years of international agencies’ humanitarian access being highly restricted into the majority of conflict-affected areas, the Tatmadaw will seek to entirely prevent access to these areas, in pursuit of its fully resumed Four Cuts strategy and purported security concerns. Needs rise in non-government-controlled areas but the Tatmadaw will declare a complete block on national and international engagement with non-state actors. This block will be enforced to the greatest extent possible. Operators caught in violation will face harsh penalties, as the Tatmadaw will aim to disincentivise noncompliance. As such, organisations’ relations with the Tatmadaw will become openly antagonistic, driving many to operate clandestinely and/or exclusively conduct activities from outside government-controlled areas.

- Local and national organisations will be listed under the Unlawful Associations Act, and CSOs must revert to clandestine operations within areas of government control. Administrative offices and bases of operations are shifted to KIO/A areas, and infrastructure and procurement activities take place in Yunnan Province. Risks for those CSOs that try to operate in forbidden areas will escalate, perhaps including even forced disappearance and extrajudicial execution. Humanitarian actors must operate under low visibility.

- Many international humanitarian agencies will be expelled from Myanmar generally and Kachin State specifically. In light of restrictions or imperatives to avoid legitimising the SAC, others will choose to suspend operations or switch to a fully covert operations model before they are formally expelled. Some expulsions will be short term — six months for alleged infractions of SAC policies, for instance — and others will be indefinite. Agencies will be vocal in their public objections to expulsions and suspensions, contributing to the appearance that these actions succeeded in shutting down their operations. Meanwhile, operations will continue without international agency visibility from within KIO/A areas and with covert logistic and infrastructure support from Yunnan Province.

- Beijing’s stance will determine the visibility and scale of cross-border aid; as mentioned above, it has indicated it will seek to curtail such activities and limit border access. Unable to establish an official presence in China, international operators will need to rely on Kachin CSOs to work through ethnic Kachin allies in Yunnan Province to obtain tacit permissions from local authorities to conduct life-saving cross-border operations. Partnerships with local and national organisations, long a cornerstone of the Kachin response, will be essential. Donors must support organisations to scale up activities to meet rising needs.

- Response actors should seek to pre-position medical supplies and increase emergency medical training and personnel presence among local partners in order to respond to IDP needs and preclude a highly visible influx of Kachin patients to Yunnan hospitals — which would likely prompt a counterproductive Beijing response. Food relief should also be pre-positioned.

- Constraints on the Myanmar financial system mean all response actors must adopt innovative approaches to money transfers, including using Hundi networks and other informal mechanisms, as well as Chinese bank accounts.

- The return and resettlement process results in some camp closures in government-controlled areas, where there is a risk of involuntary returns. However, most camps will remain operational, as a result of realities on the ground: increased displacement and inconducive conditions for returns.

[1] Figures drawn from the Assistance Association for Political Prisoners at the end of April: https://aappb.org/.

[2] See, for example: Sebastian Strangio, “Melissa Crouch on Myanmar’s Coup and the Rule of Law,” The Diplomat, 23 March 2021, https://thediplomat.com/2021/03/melissa-crouch-on-myanmars-coup-and-the-rule-of-law/

[3] Figures drawn from the Assistance Association for Political Prisoners: https://aappb.org/.

[4] William Zheng, “Coronavirus: China closes Myanmar border bridge and orders city lockdown after new cluster emerges,” South China Morning Post, 31 March 2021, https://www.scmp.com/news/china/diplomacy/article/3127751/coronavirus-chinese-city-closes-border-bridge-myanmar-and

[5] These claims are unpacked here: “Rumors are flying that China is behind the coup in Myanmar. That’s almost certainly wrong.” Washington Post, 2 March 2021, https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2021/03/02/rumors-are-flying-that-china-is-behind-coup-myanmar-thats-almost-certainly-wrong

[6] “China’s ambassador to Myanmar says situation ‘not what China wants to see’,” Reuters, 17 February 2021,

https://www.reuters.com/article/us-myanmar-politics-china-idUSKBN2AG1AA

[7] “Chinese Embassy Makes Contact with Myanmar’s Shadow Government,” The Irrawaddy, 8 April 2021, https://www.irrawaddy.com/news/burma/chinese-embassy-makes-contact-myanmars-shadow-government.html

[8] “China scrambles to lock down Myanmar border amid fears of covid and post-coup instability,” Washington Post, 9 April 2021, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/asia_pacific/covid-china-myanmar-outbreak/2021/04/09/375ac584-985d-11eb-8f0a-3384cf4fb399_story.html

[9] Chinese investments, most notably garment factories, have been targeted by anti-coup demonstrators in Yangon, but such attacks have not occured in Kachin State.