In Focus

Bangladesh Bank Freezes 1.1 Million USD in SAC Funds

Nationwide

On 17 August, Bangladesh’s state-run Sonali Bank reportedly restricted accounts — said to be holding around 1.1 million USD — owned by Myanmar state-run banks that are now under State Administration Council (SAC) control. The Sonali Bank CEO said that the US Embassy in Bangladesh had urged the bank in June to comply with US sanctions against the Myanmar Foreign Trade Bank (MFTB) and Myanmar Commercial and Investment Bank (MICB). The Sonali Bank CEO told the media that the bank had already rejected SAC requests to withdraw the money and would not unfreeze those accounts as long as the sanctions against the MFTB and MICB are in place. At a meeting with businessmen in Naypyitaw on 19 August, the chair of the Central Bank of Myanmar (CBM), which is also now SAC-controlled, said that the CBM would “retaliate” against Bangladesh — without describing how it would do so.

On 21 June, the US Treasury Department announced that it had imposed new sanctions on the SAC Ministry of Defense and on the MFTB and MICB, which it said help to facilitate currency exchanges and foreign financial flow for Myanmar and thereby enable the SAC to purchase arms and military equipment abroad. On 4 August, the US government warned that it would take action against entities that continued to do business with the MFTB and MICB. Five days later, on 9 August, Singapore’s United Overseas Bank (UOB) — widely considered the offshore bank of choice for Myanmar generals and cronies — told Myanmar banks that it would restrict all incoming and outgoing payments to and from Myanmar bank accounts as of 1 September. This week, Bangladesh appeared to become the second Asian country to act on the US government’s warnings about the MFTB and MICB. Trusted sources have told this analytical unit that the US will also apply pressure to Thailand to comply with the banking sanctions, suggesting that it may be next.

Breaking the bank

The recent bank restrictions have increased public concerns about devaluation of the Myanmar Kyat. This, along with the SAC announcing this month that it would print new 20,000 Myanmar Kyat banknotes, has caused rising exchange rates, skyrocketing prices of imported materials, and shortages of food and commodities in some areas. A housewife in Yangon’s Hlaing Tharyar Township said,

“Rice and oil are so expensive; those prices increased by one third within two months. Prices for vegetables and onions both increased. Each bag of rice cost 80,000 Myanmar Kyat in July. It increased by 40,000 Myanmar Kyat, so I now have to pay 120,000 Myanmar Kyat. The price of Thai shrimp was 9,500 Myanmar Kyat per viss. It is now worth 12,000 Myanmar Kyat.”

The devaluation of the Myanmar Kyat may precipitate a sharp rise in the need for humanitarian assistance beyond communities affected by conflicts and crises, especially among the urban poor.

Green alert

As prices rise in Myanmar, Bangladesh’s restrictions, and restrictions from Singapore’s banking sector last week, have undermined the stability of the SAC’s foreign trade, shaken export-import businesses, and led to a significant rise in the informal exchange rate, with 1 USD buying nearly 4,000 Myanmar Kyat on 18 August (from around 2,900 Myanmar Kyat to the dollar in mid-July). In response to dollar shortages caused by international sanctions, SAC leaders have asked the Bureau of Special Investigation to lead a “task force” to address rising gold and dollar prices and “take appropriate action”. As a temporary fix, the SAC permitted domestic businesses and banks to conduct business in Thai Baht. However, on 20 August, the SAC announced that it would take legal action against anyone found holding foreign currency for more than six months without authorisation, under Myanmar’s Foreign Exchange Management Law (which allows any individual to keep foreign currency not exceeding 10,000 USD in value for six months).

Collateral suffering

Sanctions are very likely to have a widespread impact on Myanmar’s economy that are likely to hit not only SAC institutions but reach local communities throughout the country. Following UOB’s announcement, Shwe Bine Phyu — a fuel import company with a majority of shares owned by SAC generals and their family members — announced that it had been liquidated under Myanmar’s Insolvency Law (2020). Petroleum oil imports from Singapore to Myanmar totalled around 4.01 billion USD in 2022. While the SAC may attempt to import more fuel from other nearby countries, shortages could hit both industry and local fuel consumption. The cost of other essential imported commodities may also rise, including fertiliser, construction materials, medicine, and electronic devices. On 17 August, Myanmar media reported that the majority of pharmacy companies had temporarily halted their wholesale purchases due to a significant increase in the exchange rate. Domestic goods will also likely rise in price, and the cost or lack of availability of rice, other foodstuffs, and more could prove a substantial obstacle to humanitarian response. In July, a senior officer from a humanitarian agency reported to this analytical unit that a high fluctuation in exchange rates could impact existing program activities by requiring local organisations to frequently revise their budgets, which some donors do not allow them to do. If inflation does increase, this could significantly impact humanitarian aid by increasing the costs of goods and services necessary to provide assistance to those in need; if the prices of basic necessities like food and medicine skyrocket due to inflation, local responders could face difficulties procuring them. Given the already existing discrepancy between humanitarian needs in Myanmar and funding available to meet these needs — with over 80 per cent of funding needs unmet for 2023 — the threat of further cost fluctuations highlights the need for contingency planning.

Guidance NoteHundi Networks: Mitigating Risks of Informal Value Transfer Systems in MyanmarThis guidance note, published on 21 August, considers the realities of working with informal value transfer systems in Myanmar. It is designed to provide international humanitarian responders, along with donors and local partners, guidance on the risks involved in such systems and how to mitigate those risks. The guidance note was precipitated by the Bank of Singapore’s announcement that it would reduce its role in facilitating transfers between banks in and outside of Myanmar, which has spurred a greater number of actors to consider alternative ways of delivering value into Myanmar. However, informal value transfer systems have long been used in Myanmar, and their use has only grown since the 1 February 2021 coup and the State Administration Council’s continued crackdown on civil society (and Myanmar banks). As the viability of transfers into Myanmar through the country’s formal banking system — already fraught for local partners — grows more difficult, this guidance note may be useful to people and organisations able to increase their usage of informal value transfer systems. To read the guidance note, please see Hundi Networks: Mitigating Risks of Informal Value Transfer Systems in Myanmar. |

Primary Concerns

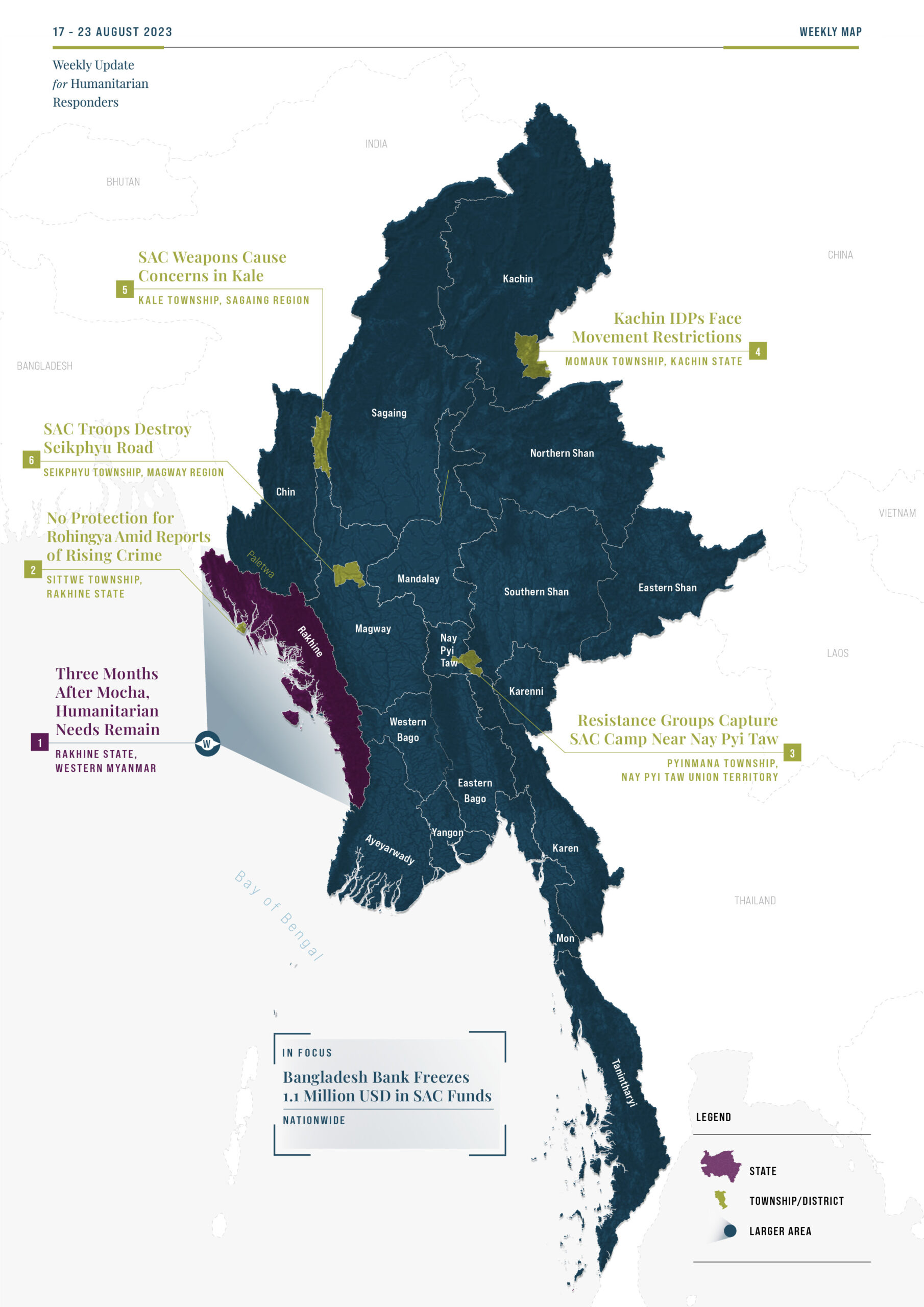

1. Three Months After Mocha, Humanitarian Needs Remain

Rakhine State, Western Myanmar

This week, sources reported to this analytical unit (and to local media) that IDPs and other communities affected by severe weather events in northern and central Rakhine State still urgently needed humanitarian assistance. It has been three months since Cyclone Mocha hit Rakhine State, and weeks since flooding early this month that, according to the United League of Arakan/Arakan Army (ULA/AA), killed six people, flooded 390 villages, and destroyed 70,537 acres of agricultural farmlands in Buthidaung, Rathedaung, Ponnagyun, Kyauktaw, Mrauk-U, Minbya, and Taungup Townships.

On 19 August, local media reported that IDPs from several camps in Rathedaung, Ponnagyun, Kyauktaw, and Mrauk-U Townships were in urgent need of food and WASH supplies, mosquito nets, and shelter materials, among other things. On 20 August, local media reported that 25 per cent of cyclone-affected communities had not yet rebuilt their shelters due to financial constraints and a lack of support. Likewise, on 18 August, local media reported that flooding-affected communities had hardly received any help. An ethnic Mro activist from Ponnagyun Township reported to this analytical unit that some communities in his area had not yet rebuilt their shelters or schools due to a lack of support since the cyclone. On 20 August, an ethnic Khami woman from Pauktaw Township told local media that she had not yet rebuilt her house for the same reasons. On 21 August, a resident at the Kyauk Ta Lone relocation site (in Kyaukpyu Township) told this analytical unit that camp residents need assistance, especially for accessing safe water, despite an NGO working on cleaning latrines and the environment at the site. The resident reported that people in the relocation site already face challenges accessing enough safe water in the rainy season and are concerned that they will face greater challenges in the coming summer and winter seasons. Residents from the areas most affected by flooding — in Kyauktaw, Mrauk-U, and Minbya Townships — reported to this analytical unit that they had received food supplies, rice rations, and NFIs from the State Administration Council (SAC), the ULA/AA, and some local CSOs and parahita groups, but that this was not enough.

Access still restricted

Humanitarian aid for communities affected by the cyclone and the recent flooding has been stymied by the SAC. On 17 August, a CSO leader told local media that their CSO had needed to stop its humanitarian activities in collaboration with UN agencies to provide relief to cyclone-affected communities because its partners had not yet received permission from the SAC. Local sources told this analytical unit that while local CSOs and parahita groups are still able to access and provide humanitarian assistance to IDPs and other communities, they also face restrictions and risk being stopped at SAC checkpoints when they attempt to carry aid, including rice bags. Indeed, local parahita leaders from Kyauktaw, Mrauk-U, and Rathedaung Townships reported to this analytical unit that SAC forces do not allow them to pass through checkpoints while carrying humanitarian aid without permission from the Rakhine SAC (RSAC) Minister of Security and Border Affairs. They also said that the SAC’s increased security checks and inspections on movement of people and aid groups has limited the amount of humanitarian assistance that can reach cyclone- and flooding-affected communities. Camp leaders from Nyaung Chaung IDP camp in Kyauktaw Township and Sit Thaung IDP camp in Mrauk-U Township reported to this analytical unit that SAC restrictions, delays in issuing travel authorisations, and checkpoint inspections have hurt IDPs’ ability to bring rice from aid groups elsewhere and prevented both local and international agencies from delivering humanitarian assistance. One noted, however, that some agencies have been able to transfer money electronically (via Wave Money or K Pay) and through Hundi networks as stop-gap alternatives. Local sources stressed that remote cash assistance remains the most feasible means of assisting communities.

Can UN visit translate into access?

Amidst all this, a high-profile visit to the state was notable but no guarantee of relief, in light of the SAC’s ongoing restrictions. On 16 August, UN Under-Secretary General for Humanitarian Affairs and Emergency Relief Coordinator Martin Griffiths arrived in Rakhine State, a day after meeting with SAC leader Min Aung Hlaing to discuss humanitarian aid in Myanmar, including cyclone Mocha rehabilitation. During the trip, he met with RSAC personnel and the Shwe Zaydi Sayadaw (a revered monk), and visited camps hosting Rakhine and Rohingya people in Sittwe Township. On 18 August, the monk told local media that during the meeting, he had discussed and requested “effective assistance” for rehabilitation. Also on 18 August, an RSAC spokesperson told local media that the RSAC discussed topics with the UN official including provision of humanitarian assistance to cyclone-affected people, regional stability, and the pilot repatriation of Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh. However, on 17 August, local media reported that, despite the SAC allowing the UN official to travel in Rakhine State and observe the consequences of the cyclone, restrictions on the provision of humanitarian assistance to cyclone-affected people continue.

2. No Protection for Rohingya Amid Reports of Rising Crime

Sittwe Township, Rakhine State

On 17 August, five ethnic Rakhine youths reportedly beat and robbed a 25-year-old Rohingya man from Thet Kay Pyin village who was heading to work at a Rakhine house in downtown Sittwe, taking his phone, money, and motorbike. The attack reportedly took place in front of the Sittwe fire station and in the presence of three State Administration Council (SAC) traffic police. This is not an uncommon occurrence for Rohingya people. According to a witness who spoke to this analytical unit, on 8 June a group of Rakhine youths beat and stole 250,000 Myanmar Kyat (around 120 USD) from a Rohingya man in Sittwe’s Ywa Gyi Taung ward as he was travelling to repay a Rakhine person from whom he had bought materials to rebuild after Cyclone Mocha. Another Sittwe resident told this analytical unit that in the first week of June, a group of Rakhine youths on motorbikes stole a motorbike from a group of six Rohingya teenagers visiting the seaside Sittwe Point. When the victims reported the robbery to the traffic police, the resident said, the police extorted 100,000 Myanmar Kyat (around 47 USD) from them instead of addressing the theft. Rohingya people told this analytical unit that they are concerned about going to downtown Sittwe by motorbike to work or access markets due to the lack of protection.

The reported rise in crime has not only been noticed by Rohingya residents, although the lack of protection from police likely makes Rohingya people more vulnerable to it. On 20 August, local media reported that ethnic Rakhine locals are increasingly concerned after a surge in theft and violent crime — citing the robbery of a house in broad daylight and the discovery of unidentified corpses in downtown Sittwe. The report alleged that women are particularly vulnerable and are concerned about travelling to town due to the lack of security.

Out of uniform, out of line

Recent incidents illustrate the lack of protection for Rohingya people in Rakhine State, where police appear more likely to exploit Rohingya crime victims than to assist them. On 20 August, local media reported that for two months, two policemen from police battalion No. 36 in Sittwe — though apparently out of uniform — had been abusing and extorting money from Rohingya car and auto trishaw drivers carrying goods or materials through the Hmanzi police checkpoint, which many Rohingya from nearby camps must use when travelling for access to services, livelihoods, and key markets. Reportedly, Rohingya first believed the men to be civilians trying to create violence between communities, because they were not in police uniforms. The two policemen are said to have charged 20,000 Myanmar Kyat (around 10.50 USD) for a small truck and 13,000 Myanmar Kyat (around 6 USD) for a trishaw to pass the checkpoint if they were carrying any commercial goods. Meanwhile, traffic police have reportedly targeted Rohingya motorbike riders elsewhere in the city, checking their driver’s licences or other documents, and extorting money from them. The particular vulnerability of Rohingya to the apparent recent rise in crime must be understood in connection to the structural discrimination they continue to face, including not only restrictions on movement, citizenship, access to livelihoods and other basic rights, but also the absence of any real protection from armed actors or security forces.

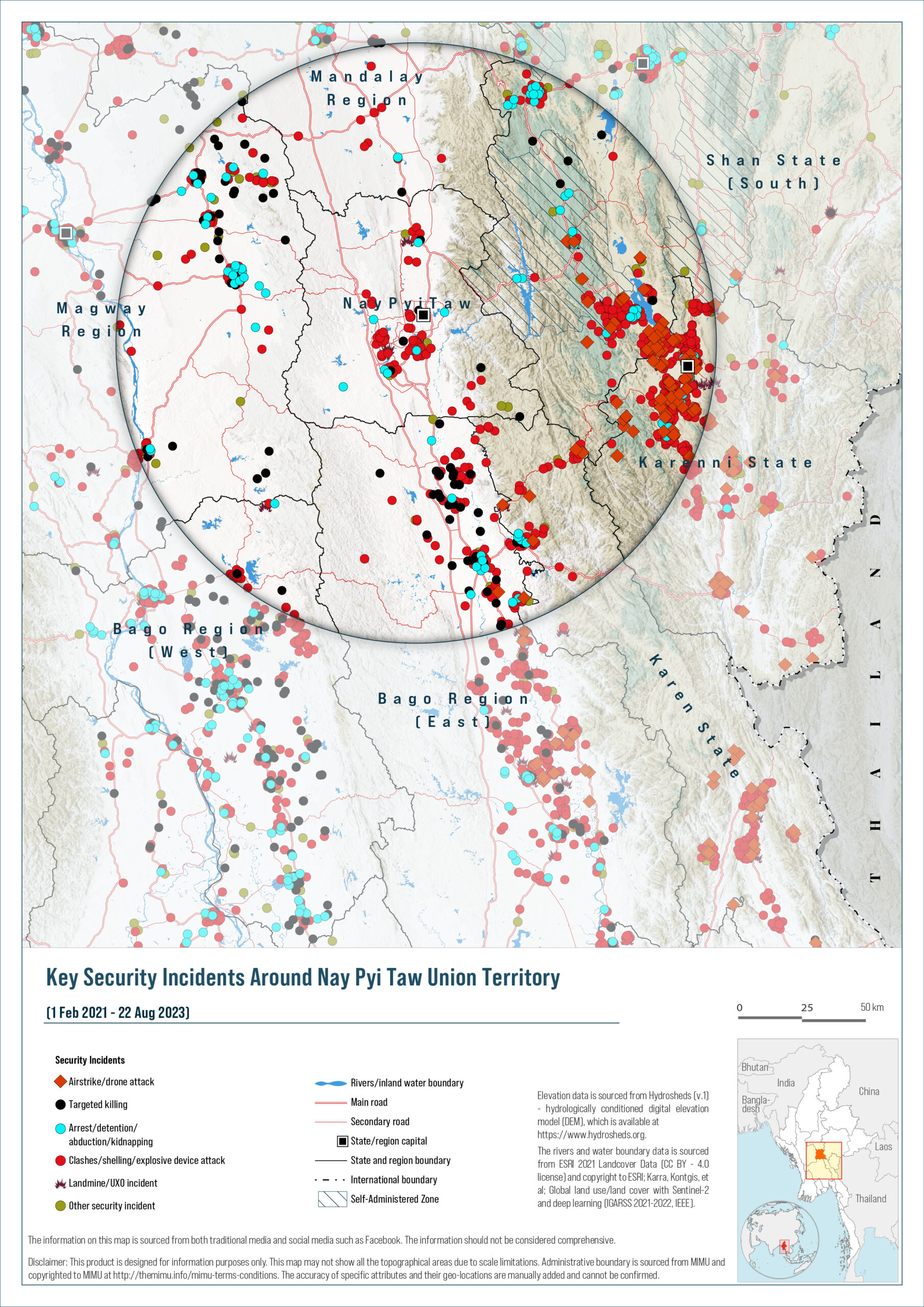

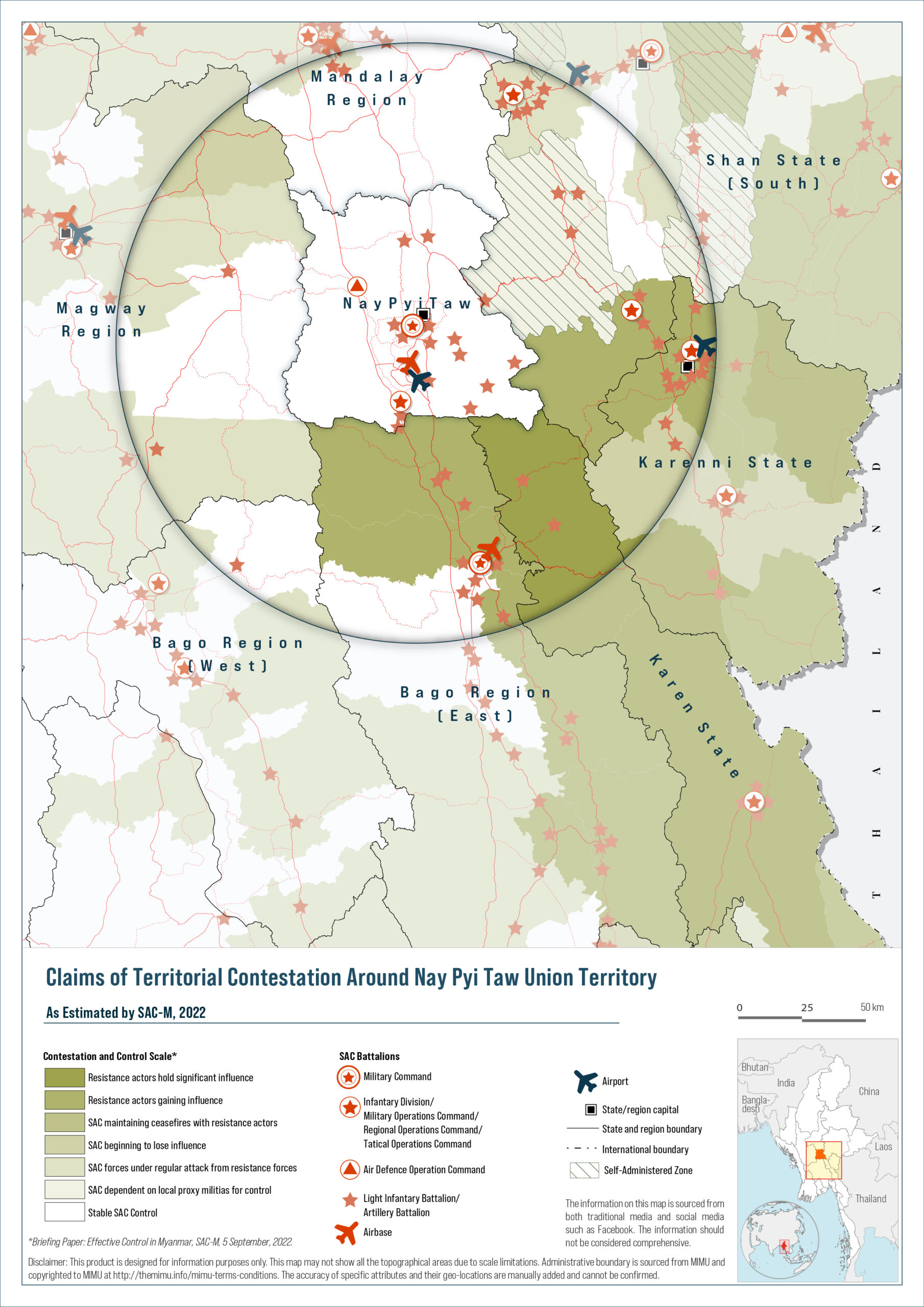

3. Resistance Groups Capture SAC Camp Near Nay Pyi Taw

Pyinmana Township, Nay Pyi Taw Union Territory

Between 10 and 13 August, several armed resistance actors trained by the Karen National Liberation Army (KNLA) captured and razed the State Administration Council’s (SAC) Boma Thandaung base in Pyinmana Township. The hill fortification had reportedly helped the SAC to control movement to and from Karen State and the embattled Karenni-Shan State border towns of Moebye and Pekon. On 10 and 11 August, the Iron Tiger Battalion, composed of fighters from Karenni State- and Karen State-based People’s Defence Forces (PDFs), reportedly repelled the SAC reinforcements sent to retake the base. Although Iron Tiger retreated from the position on 11 August, it first destroyed the base, and now its fighters continue to block SAC troops’ access to the site. On 13 August, fighting broke out in Yepu Aung Khaung village (at an intersection along the Taung Myint Road, which connects Pyinmana and Nay Pyi Taw), where the resistance group has positioned itself to prevent SAC troops from reaching the hill. Local media claimed that around 50 SAC troops and three resistance fighters died in the fighting at the Boma Thandaung base, during which the SAC reportedly conducted airstrikes against villages in eastern Pyinmana Township. Local media reports, some of which suggested the strikes were reprisals against civilians, said that some houses were destroyed, a civilian was killed, others were detained and used as human shields, and an indeterminate number were displaced.

Hill base blues

The seizure of the base highlights the growing operational ability and reach of ethnic armed organisations (EAOs) and armed resistance actors in southeastern Myanmar, as well as the likelihood of an increased need for humanitarian support in areas hitherto less impacted by fighting. Although resistance groups have staged sporadic attacks in Nay Pyi Taw Union Territory since the coup, the loss of the Boma Thandaung base is the first reported example — known to this analytical unit — of anti-coup armed actors capturing SAC bases there. The National Unity Government (NUG) defence ministry spokesperson said in a video interview that the captured base is just 25 miles south of Nay Pyi Taw town — though another outlet has the distance at 70km (~43 miles) — and that it is the last SAC outpost before reaching the capital. He said the SAC’s failure to retake the base or prevent its destruction “shows that the SAC’s command structure is broken”. NUG representatives and leaders of its Central Command and Coordination Committee have expressed a firm belief this month that victory against an over-stretched SAC is coming ever closer. However, despite the NUG defence minister saying after the base’s seizure that his forces aim to extend operations all the way to the capital, the NUG still faces logistical and manpower limitations that would discount an imminent march on heavily fortified Nay Pyi Taw.

KNLA: Sittaung pretty

The fighting in Nay Pyi Taw Union Territory, along with the recent intensification of armed violence in Bago Region, suggests that armed resistance actors in Myanmar’s southeast may be expanding their areas of military operation. The push by resistance actors into Pyinmana Township comes after a period of consolidation on both sides of the Bago Yoma mountain range and around the Sittaung river basin, an important area for revolutionaries of both the Karen National Union (KNU) and Communist Party of Burma in previous eras. The NUG’s Southern Region Command has expressed that the area, which connects Yangon to Nay Pyi Taw, and eastern Myanmar to northwestern Dry Zone warscapes (and relatively peaceful Ayeyarwady Region), is a key resistance battlefield. In early 2023, it announced that, after roughly one and a half years of training and organising troops in Bago, it now has two well-equipped PDFs in each of Bago Region’s four districts. According to a March article by Frontier, these groups say they defer to the sphere of influence asserted by the KNU, and have cooperated with it in attacks on military camps, police stations, and other SAC infrastructure. Fighting has notably intensified south of Pyinmana Township in Yedashe in Taungoo Township, and in territory claimed by KNLA Brigade 3, including areas of Shwegyin and Nyaunglebin Townships. With the support of new Bago Region and Karenni State-based armed actors, the KNLA says it has significantly widened its operational range. In an apparent attempt to stem the tide, the SAC put five Bago townships under martial law in February. In response to heavy fighting this month in Kyuaktaga Township, the KNLA issued travel warnings while the SAC reportedly cut cellular service to the area.

Bringing the war home

Because of the Boma Thandaung base’s proximity to the capital and its logistical importance to the SAC, this week’s developments are likely to be followed by protracted and fierce fighting in southeastern Pyinmana Township, as has been seen around other captured SAC bases. Since the KNLA and allied PDF fighters seized the SAC’s Lat Khat Taung base — seven miles from Myawaddy town — in late July, fighting between these joint fighters and SAC troops have reportedly displaced over 500 people. The SAC has continued to try, but has so far failed, to retake the Lat Khat Taung base. Similarly, SAC attacks — whether raids, airstrikes, artillery shelling, or some combination thereof — have consistently targeted civilian populations following losses to PDFs or EAOs; again, it is civilians who are most likely to bear the brunt of SAC attacks in Pyinmana Township. Northern Karen State and Eastern Bago Region have experienced increases in displacement, arbitrary arrests, and abuses since the turn of the year; the KNU says that, in July alone, the SAC launched 33 airstrikes against the northern part of the territory the KNU considers to be under its control, which includes part of the region in question. As the SAC continues to carry attacks against civilians — characterised as “collective punishment” by Amnesty International — following armed violence, civilians continue to be displaced and their lives, health, and livelihoods made more insecure.

4. Kachin IDPs Face Movement Restrictions

Momauk Township, Kachin State

On 15 August, local media reported that 183 families displaced from four villages in Momauk Township who had taken refuge in Dawthponeyan town, Momauk Township, were unable to return to their farms and risked losing their crops. The IDPs, from Dinggar, Nawngwant, Khalar, and Teinjang villages, had been displaced by fighting in early July along the Myitkyina-Bhamo road. Reportedly, the State Administration Council (SAC) has not allowed them to leave their (temporary) displacement site, and the Kachin Independence Army (KIA) has warned them not to return due to security concerns related to ongoing tensions. IDPs told local media they feared for their livelihoods if they were not allowed to return, as they would lose their annual crop, and had concerns over broader food scarcity driven by mass displacement. An IDP taking refuge in the Dawthponeyan Kachin Baptist Convention (KBC) church compound told this analytical unit that IDPs there were grappling with challenges related to food and shelter, with many families temporarily sheltering in religious buildings. Their host community is reported as saying it plans to construct dwellings to house them in October, after their third month of displacement. A Dawthponeyan host community member assisting them told this analytical unit that, despite likely being able to temporarily resettle in Bhamo Township, IPDs wish to wait indefinitely in Dawthponeyan, closer to their farms.

Road to Mandalay restricted

The 15 August report highlights some of the difficulties facing newly displaced communities in Kachin State amid tensions between the SAC and the KIA. Barriers to movement are likely to create further challenges to their accessing livelihood activities, markets, and healthcare, and neither are the safety or security of the region’s IDPs guaranteed. On 11 August, a male IDP transporting rice donated to IDPs in Kazuyang village was arrested at an SAC checkpoint and accused of working for the KIA. Such incidents highlight the significant risks associated with aid provision in the region. Furthermore, those IDPs living in established camps face a bevy of challenges as the SAC continues its apparent attempts to shut down IDP camps across the state, despite the same drivers of past displacement constituting barriers to return or relocation.

Fighting has centred along the Myitkyina-Mandalay road, affecting civilians in Waingmaw, Bhamo, and Momauk Townships. Although fighting has subsided since early August, tensions in the area remain high and reports claim the SAC has fired artillery from its camps along the route. It appears that the SAC is using a lull in fighting to reinforce its troops, possibly to prepare for prolonged armed violence in the state: nine SAC vessels that had set up the Irrawaddy River from Mandalay on 26 July reached Bhamo town on 20 August. Kachin media reported that, in response to repeated attacks by resistance groups along the river, SAC-allied militia from Northern Shan State were posted to reinforce the military’s presence in Bhamo town, raising the spectre of further displacement in Bhamo, Momauk, and Waingmaw Townships. Since the vessels arrived in Bhamo, the SAC has tightened security both in and around the town, reportedly prohibiting civilians from leaving unless working in SAC departments. Access to major transport routes, like the Bhamo-Myitkyina, Bhamo-Mandalay, and Bhamo-Lwegel roads — the last of which connects to a Myanmar-China border crossing — have been severely restricted. If these restrictions remain in place, they could significantly impact both IDPs living in areas under SAC control and those in areas under KIO control. In addition, IDPs in KIO-controlled areas, who are dependent on (limited) imported goods from China, continue to be affected by the Myanmar Kyat’s weakening value against exchange currencies.

Scenario Plan: Kachin State, August 2023

This Scenario Plan presents Kachin State-based context projections for the purposes of response planning and strategy, including a possible scenario in which fighting between the KIA and SAC escalates dramatically over the coming months. While this Scenario Plan provides general guidance, responders may make adaptations to suit the needs, priorities, and strategies of their respective organisations.

To read the report, please see Scenario Plan: Kachin State, August 2023

|

5. SAC Weapons Cause Concerns in Kale

Kale Township, Sagaing Region

On 15 August, after People’s Defense Forces (PDFs) attacked State Administration Council (SAC) troops with explosives, SAC forces launched a series of attacks and raids lasting at least five days. Over this period, they reportedly burned down about 800 of the 1,500 houses in Tharsi village, Kale Township, and killed five villagers. On 15 August, an SAC Mi-35 helicopter provided air support, firing on Tharsi village and hitting two men and some livestock. SAC troops in Kale town fired artillery shells that landed in Tharsi and two other villages, killing a nine-year-old child. Residents of around 10 villages fled the raids and continued SAC presence — most sheltering with relatives or in a monastery in Kale town. One Tharsi resident said that villagers have not been able to retrieve the bodies of those killed, as SAC troops remain in the village; another told this analytical unit that those displaced had been unable to bring supplies when they fled and would soon need food and clothes.

Smoke effects

Villagers reported concerns about the types of weapons used by SAC forces in the attack. Reportedly, at least some of the weapons that the SAC fired into Tharsi village caused villagers to get sick; around 20 people sought medical treatment. Villagers said that SAC shells and bombs emitted a smell, and that accidental inhalation of the fumes caused a burning sensation in the throat, an increase in body temperature, a drop in blood pressure, achiness, numbness, shortness of breath, and temporary unconsciousness. Local media reported that those affected — both PDF fighters and civilians — experienced nausea and vomiting, and difficulty walking. The top medic from the Kale PDF said that this was the first time that the group had needed to give medical treatment for emissions from SAC weapons and that her team was examining whether or not it was a chemical weapon. A Kale PDF member told this analytical unit that the weapon caused people to have stomach aches and blood in their urine and stool, to feel weak or dizzy for days, or even to become unconscious. He said that the weapon burned and emitted light grey smoke on impact — rather than exploding — and was a little bit bigger than a 120mm shell. He said that both the helicopter and the SAC ground troops fired weapons with this effect, which only affected people close to where the weapons detonated but also killed several pigs.

A villager from Tamu Township told this analytical unit that on 18 August, the SAC used weapons with similar effects in Tamu as well, affecting over 50 people. The villager said that people were getting treatment for their symptoms in India, but that there were not enough beds or medicine for all of these people. Since the coup, similar reports have emerged from elsewhere, including Kachin State in May 2021 and Karen State in April 2022. It is widely suspected that Myanmar continues to retain stockpiles of chemical weapons, in spite of joining the Chemical Weapons Convention in 2015, which bans the production, storage, and use of chemical arms. In 2019, the US publicly accused Myanmar of continuing to hold chemical weapons stockpiled since the 1980s, including mustard gas. While this analytical unit cannot confirm the types of weapons used by the SAC in any of these instances, reports of symptoms brought on by weapons’ emissions raise serious concerns.

6. SAC Troops Destroy Seikphyu Road

Seikphyu Township, Magway Region

On 18 August, State Administration Council (SAC) troops reportedly used bulldozers to destroy three intersections on a road connecting 10 villages to Seikphyu town and threatened to burn down the houses around the road if the residents repaired the road. SAC troops had blocked access to Seikphyu town since 12 July, and local sources told this analytical unit that since then, access to the town has been possible but more costly. Transportation is now further disrupted, and likely to remain so, for around 10 villages that use this road to go to Seikphyu town for food, healthcare needs, trade, or other business. A Seikphyu People’s Defence Force (PDF) spokesperson reported that without the use of this road, an alternate route would add at least two hours to the journey to town. SAC troops remain stationed around the damaged route, so no residents can use or repair it. A local said that the SAC is intentionally disrupting people’s movement and access to markets.

Foodblock

While the road destruction may have been in response to PDF activity, it is most likely to impact civilians living in the area. The SAC has an established pattern of ‘punishing’ populations it perceives as supportive of resistance groups, and this seems to fit that pattern. PDFs have raided SAC camps, police stations, and Pyu Saw Htee villages in Seikphyu Township, and fighting between SAC troops and PDFs fighters has escalated in the township since early July. The SAC has restricted the carrying of food, mainly rice and oil, and medicines — and even blocked travel for patients who needed emergency healthcare. The destruction of the road suggests that the SAC had been unable to totally control the road through checkpoints or other physical measures, as it has done frequently throughout Myanmar. While civilians — including IDPs and host communities — may now struggle to access food and other commodities, the road destruction has not prevented further PDF attacks: on 20 August, the Seikphyu PDF detonated an explosive in front of the Seikphyu Department of Home Affairs and Immigration, seriously injuring two SAC personnel.