Syria Update

06 December to 12 December, 2018

The Syria Update is divided into two sections. The first section provides an in-depth analysis of key issues and dynamics related to wartime and post-conflict Syria. The second section provides a comprehensive whole of Syria review, detailing events and incidents, and analysis of their respective significance.

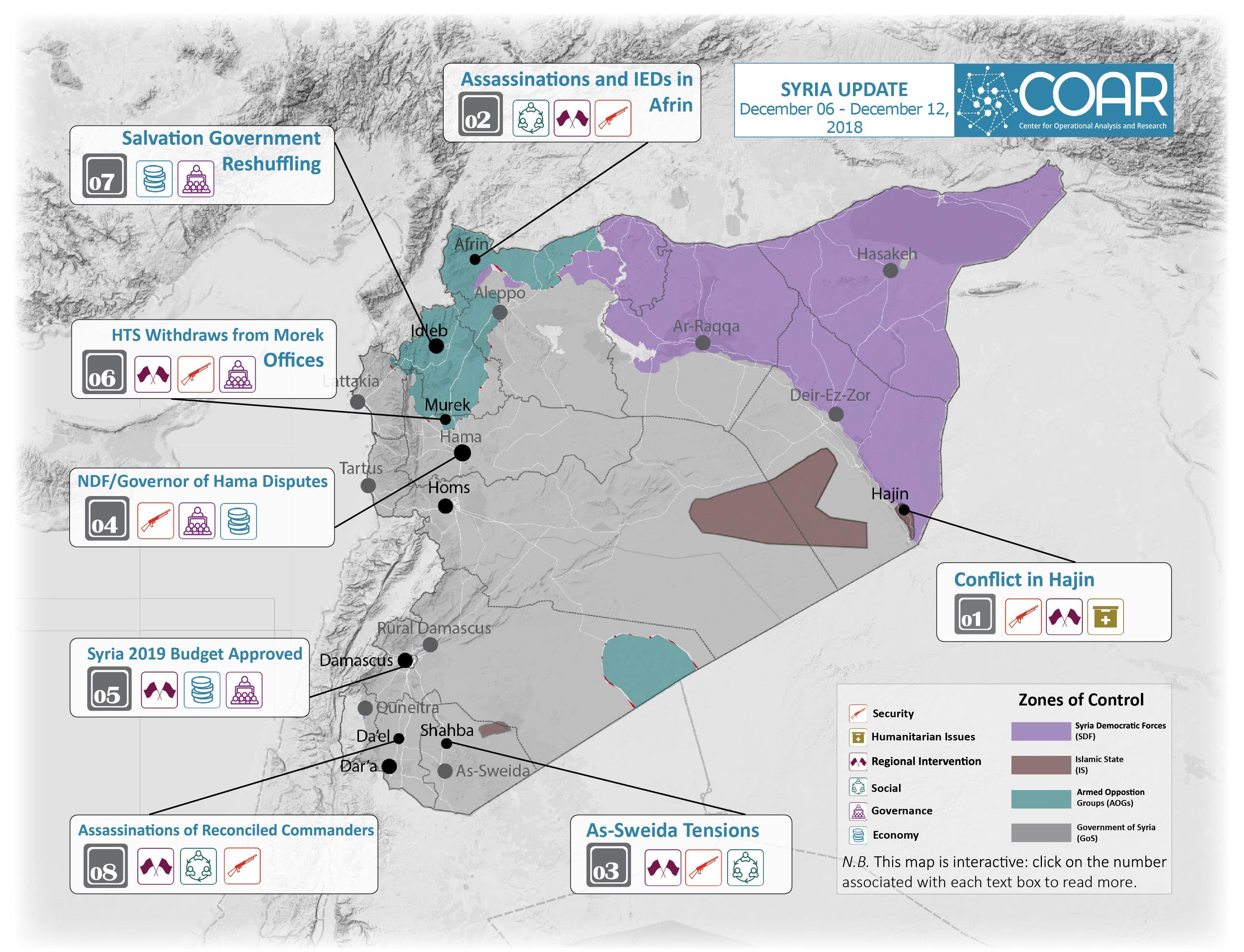

The following is a brief synopsis of the in-depth analysis section this week:

On December 6 and 7, Lebanese security forces reportedly detained and subsequently deported approximately 1,000 Syrian refugees. Though no public statement has been made, this incident appears to mark the first large-scale forced return of Syrian refugees from Lebanon. According to recent analysis, fears of detention and concerns related to conditions in Syria have impeded many voluntary returns, and indeed the issue of voluntary returns has also been a major source of consternation for those responding to the Syria crisis. While this particular incident is noteworthy, it is also important to highlight the fact that Lebanon does not, nor is likely to have, a formal state policy with respect to Syria refugees and accompanying returns. Lebanon has not officially formed a government, and individual ministries and directorates are controlled by disparate group of individuals affiliated with rival Lebanese political parties. Rather, Lebanese ‘policy’ with respect to Syrian refugees appears to be implemented haphazardly, with decisions based on domestic political agendas and grievances. That said, the Lebanese Parliament will eventually form a Government, and this Government will likely take a more aggressive approach toward Syrian refugees in Lebanon.

The following is a brief synopsis of the Whole of Syria Review:

-

Heavy conflict continues between the SDF and ISIS in Hajin, leading to the destruction of the city’s primary hospital; the conflict in Hajin is likely to conclude in the near to medium term, and the humanitarian needs stemming from the Hajin offensive will be immense.

-

Armed men in As-Sweida governorate from the Druze community expelled a group of Russian Military Police from the village of Shahba. Recent Russian efforts to re-structure Druze armed groups in As-Sweida governorate may exacerbate the considerable tensions between the Government of Syria and the Druze community over conscription issues.

-

The Head of the Da’el Reconciliation Committee, as well as a former armed opposition commander, were assassinated in Dar’a Governorate. It is unclear who is responsible for these assassinations, though local rumors variously accuse either disgruntled former armed opposition groups or the Government of Syria. This incident, and the accompanying accusations, highlight the complex political and security dynamics in recently reconciled areas.

-

Assassinations and IEDs continue to target Turkish-backed armed opposition combatants in Afrin. While the majority have been claimed YPG sleeper cells, continued tensions between competing Turkish-backed armed groups have also been a major source of local instability in Operation Olive Branch-held areas, and inter-opposition conflict cannot be discounted.

-

Syrian President Bashar Al-Assad issued the 2019 Syrian budget; while cited as a budgetary increase, the 2019 budget instead reflects Syria’s dire economic and monetary conditions, especially its inability to fund reconstruction and its reliance on foreign partners.

-

Hay’at Tahrir Al-Sham withdrew from the key Morek crossing point, which coincided with reports of deployments by Iranian and Government of Syria-affiliated armed actors in western rural Hama governorate. Although unclear, Hay’at Tahrir Al-Sham’s withdrawal could either be an indication of their attempt to comply with the northwest Syria disarmament agreement, or of their preparation for a renewed Government of Syria offensive.

-

The Hay’at Tahrir Al-Sham-affiliated Salvation Government reshuffled several key ministry positions, merged other ministries, and appointed a new Prime Minister. It is likely that the reshuffling is related to the lack of available funding, thereby requiring the Salvation Government to consolidate revenue-generating ministries and directorates into more centralized bodies.

-

The Governor of Hama was prevented from entering the village of Qamhana by local NDF groups reportedly due to local concerns that the purpose of his visit was to crack down on smuggling operations. This incident highlights the considerable command and control issues facing the Government of Syria due to its limited control over the myriad pro-Government local militias.

Forced Returns and Internal Divisions in Lebanon

In Depth Analysis

On December 6 and 7, Lebanese security forces conducted a series of raids in the vicinity of Arsal, and reportedly detained approximately 750 Syrian refugees, including entire families, women, and children. Those detained subsequently joined an additional 250 Syrian individuals who had been previously arrested or detained by Lebanese security forces across Lebanon, and the total group consisting of 1,000 individuals were delivered to “Syrian authorities at the Syrian border.” According to Anwar Al-Bounni, a prominent Syrian human rights lawyer, Lebanese General Security claimed that these ‘returnees’ had previously signed documents stating that they had promised to return to Syria; however, Al-Bounni has challenged this assertion, implying that these documents, if they do indeed exist, were signed under duress. He also noted that if these 1,000 individuals wished to return to Syria on their own, there would be “no need for raids, arrests, and forced surrender.” According to local sources, the majority of those who were delivered to the Syrian border originated from northern rural Homs. If confirmed, this incident marks the first large-scale forced return to Syria from Lebanon. As of December 13, the fate of the recent returnees upon entering Syria remains unclear.

There are many factors impacting and impeding voluntary returns to Syria; as noted in ‘Unheard Voices: What Syrian Refugees Need to Return Home’, a recent study by the Carnegie Middle East Center, a majority of Syrian refugees in neighboring states are unwilling to return unless a political transition can assure their “safety and security, access to justice, and right of return to areas of origin,” none of which concerns have been sufficiently addressed thus far. According to UN and local NGO partners, only 46,768 individuals have returned from neighboring countries to Syria between January and October 2018; of these, 11,921 refugees have returned from Lebanon, a mere fraction of the approximate 1.1 million Syrian refugees in the country according to UNHCR. The fear of forced or premature returns from Lebanon, Turkey, or Jordan, has been a major source of concern and advocacy for the international and local response to the Syrian crisis, due to both the significant ethical and moral considerations and the fact that a premature or forced return would have a disastrous impact on the already poor humanitarian conditions in many parts of Syria.

While reports of large-scale forced returns from Lebanon are troubling, it should not necessarily be taken as indicative of Lebanese state policy with respect to Syrian refugee return. Political appointments and policies of individual ministries and directorates have not taken place since the May 2018 Lebanese parliamentary elections; directives and policies for individual Lebanese ministries remain diffuse with regards to Syrian refugees, and are underpinned by the political rivalries within the caretaker Lebanese government. Indeed, while all of Lebanon’s major political parties have expressed their preference to facilitate the return of Syrian refugees to Syria, Lebanon’s political parties differ strongly on their stance toward the Government of Syria, and the vulnerability criteria and means by which Syrian refugees should return. Therefore, in effect there is currently no single ‘Lebanese policy,’ but rather numerous Lebanese policies, depending on individual officials, ministries, and directorates.

The asynchronous treatment of and rhetoric towards Syrian refugees has been apparent throughout the past several months. The forcible detention and return of refugees to Syria in the past week was supposedly conducted by Lebanese General Security, which is reported to take into consideration the political perspective of Lebanese Hezbollah. Similarly, in June 2018, Foreign Minister Gibran Bassil ordered the freezing of UNHCR expatriate staff residency applications in Lebanon, claiming that UNHCR was “spreading fear” amongst Syrian refugees by discouraging returns to Syria; Bassil is a member of the Free Patriotic Movement, a Hezbollah-allied political party, led by Lebanese President Michel Aoun, which strongly advocates for Syrian refugee return and closer ties with the Government of Syria. In contrast, the Lebanese Minister of Refugee Affairs, Mo’in Mourabi, has issued numerous statements over the past two months condemning Lebanon’s handling of Syrian returns, and has claimed that numerous Syrians who have returned have been detained or killed. Mourabi is a member of the Future Movement, the primary Sunni political party in Lebanon, led by the Lebanese Prime Minister Saad Hariri, which has consistently been opposed to both the Government of Syria and Lebanese Hezbollah, and therefore against the forcible return of Syrian refugees in Lebanon.

Considering the major divisions within the current Lebanese caretaker Government, it is unlikely that Lebanon will form a government or a unified political policy with respect to the issue of Syria refugee return in the near term. Indeed, the issue of refugee return is only one of many issues dividing Lebanon’s numerous political blocs; issues surrounding Lebanon’s stance toward the Government of Syria, oil and gas contracts, public infrastructure projects, political-sectarian representation, and the dire state of the Lebanese economy also divide Lebanon’s political parties.

Whole of Syria Review

Conflict in Hajin

Hajin, Deir-ez-Zor governorate, Syria: As of December 7, clashes between the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), with heavy support by U.S.-led coalition airstrikes, and ISIS combatants continued near Hajin, in eastern Deir-ez-Zor governorate. On December 7, Government of Syria-affiliated SANA news agency reported that the U.S.-led coalition airstrikes destroyed the Hajin National Hospital, which resulted in the death of numerous civilians. On December 10, the SDF released a statement announcing they had secured significant advances along Hajin and Upper Baguz frontlines, and secured the Hajin National Hospital in central Hajin town; in apparent response to the SANA report, the SDF claimed that the hospital was destroyed when ISIS combatants detonated IEDs in the hospital prior to their withdrawal. Separately, significant SDF reinforcements have since reportedly arrived from Menbij in northern Aleppo to support the U.S.-led counter-ISIS ‘Jazeera Storm’ Operation in Deir-ez-Zor governorate.

Analysis: It is unclear how the Hajin National Hospital was destroyed. According to Operation Inherent Resolve press releases, a total of 781 airstrikes have targeted the ISIS-held Hajin since October 21; the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights has also reported that U.S.-led coalition airstrikes have resulted in the death of at least 265 civilians since November 2018. Notably, there are approximately 84,238 individuals currently residing in the ISIS-controlled areas surrounding Hajin according to UN and local NGO partners; in addition to heavy levels of conflict, the area has also faced siege conditions since early September 2018. With the arrival of significant SDF reinforcements to the front lines, and heavy U.S. aerial support, it is likely that the SDF will secure the remaining ISIS-held pockets in Deir-ez-Zor in the near- to medium-term. As in all densely populated areas succumbing to siege conditions, such as eastern Aleppo city or Eastern Ghouta, the humanitarian needs, deprivation, and casualties stemming from the Hajin offensive are likely to be immense.

Assassinations and IEDs in Afrin

Afrin District, Northern Aleppo, Syria: On December 10, the YPG claimed responsibility for two IED explosions in Bulbul subdistrict in Afrin, and has claimed responsibility for several other assassination attempts targeting Turkish-backed armed opposition combatants in the area in the past two weeks. A second IED killed several Turkish-backed armed opposition combatants in Baia village, also in the vicinity of Afrin; this IED was attributed to the YPG by local sources. Notably, two additional, yet unattributed, IEDs also targeted combatants from Faylaq Al-Sham and Sultan Murad, two prominent Turkish-backed armed opposition groups in Afrin, throughout the past week.

Analysis: IED attacks, clashes, and assassinations in Afrin are frequent; while Kurd-Arab tensions in Afrin are extremely high, Turkish-backed armed opposition infighting is also common. Although the Government of Turkey took control of Afrin district following Operation Olive Branch in March 2018, YPG forces continue to maintain sleeper cells in the area and regularly launch reprisal attacks against Turkish-backed groups. However, not every IED or assassination in Afrin should be attributed to the YPG, as Turkish-backed armed groups regularly engage in clashes with one another, generally over control of the local war economy or appropriated housing. Therefore, the precarious security situation in Afrin is unlikely to improve for the foreseeable future.

As-Sweida Tensions

As-Sweida governorate, Southern Syria: On December 6, several armed men in Shahba village, As-Sweida governorate, expelled a Russian Military Police unit patrolling the area. Though the exact motivation behind the expulsion is unclear, it is reportedly related to recent Russian Military Police attempts to restructure and centralize armed group formations in As-Sweida and increase the frequency of conscription campaigns in the governorate. Russian Military Police have recently convened several meetings with local Druze armed groups in As-Sweida governorate, to include the Shouyoukh Al-Karama. Reportedly, the Russian Military Police have been in negotiations with Druze armed groups in order to create more formal structures. Of note, the Shouyoukh Al-Karama is a Druze armed group and social movement that is not necessarily opposed to the Government of Syria politically, but is very much against the conscription and deployment of Druze individuals outside of As-Sweida governorate.

Analysis: Tensions between elements of the Druze community and Russian Military Police likely stem from a series of incidents in July 2018. In late-July, ISIS kidnapped numerous Druze women and children in an attack across numerous communities in As-Sweida. Immediately following the kidnappings, Maher Al-Assad, the leader of the of the 4th Division (and brother of President Al-Assad) proposed, in a Russian facilitated meeting with Druze community representatives, that all military-aged Druze males adhere to conscription policies and join the Syrian Arab Army’s 1st Corps; in return, the Syrian Arab Army would defeat ISIS in the area and free the Druze hostages. Several Druze community representatives were open to these terms; however, no official agreements were implemented. On November 8, Druze hostages were rescued by Government of Syria military forces; since that time, the Government of Syria has exerted pressure on the Druze community to increase conscription numbers, despite continued local protests. Considering the role Russia played in facilitating these local negotiations, and its function more broadly as both a guarantor of local agreements and a supporter of the Syrian State, it is not surprising that Russia has attempted to centralize and formalize Druze militias. Yet by doing so, Russia appears to have encountered it appears to have earned the ire of the Druze community of As-Sweida. More broadly speaking, it is unlikely that the Government of Syria will actually take any serious steps to conscript or exert further central control over the Druze community, given their unique geopolitical position, and so it is unclear why Russia has chosen to do so.

NDF/Governor of Hama Disputes

Qamhana, Hama Governorate, Syria: On December 9, Mohamad Al Hazouri, the Governor of Hama governorate, entered Qamhana village accompanied by police forces, in order to confiscate smuggled goods in the village, which reportedly included Turkish goods channeled through opposition-controlled areas in northwestern Syria. His entrance was reportedly prevented by local inhabitants of Qamhana as well as the head of the Qamhana Military Committee, the primary NDF coordination body in Qamhana. Notably, local sources report that traders in Qamhana provide local NDF militias with both financial kickbacks and a portion of the smuggled products in return for facilitation of smuggling and protection.

Analysis: The fact that local residents and their associated militias can prevent a governor from entering a community is an indication of the growing role and power of the myriad armed actors in Syria; it also highlights that this growing power comes at the expense of Syria’s bureaucratic and administrative governance bodies. The disaggregated and highly localized nature of the Government of Syria’s aligned militants further exacerbates these fissures. Not only does this incident demonstrate the limited power the Government of Syria’s regional representatives, appointees, and other public employees, it also highlights the Government of Syria’s current inability to fully control its forces within a clear command and control structure. For more information on these dynamics, Khedder Khaddour recently discussed some the challenges faced by the Government of Syria when controlling its diffuse militias in a recent article.

Syria 2019 Budget Approved

Damascus, Syria: On December 6, Syrian President Bashar Assad issued the 2019 Syrian National Budget, following Syrian Parliamentary approval in October 2018. The 2019 budget is totaled at 3.88 trillion SYP ($7.8 billion USD), an increase of 19.8% from the 2018 Syrian budget. The 2019 budget allocates 811 billion SYP ($1.6 billion USD) for ‘social support,’ which is further allocated as follows: 361 billion SYP ($727 million USD) for flour subsidies, 430 billion SYP ($866 million USD) for gas and fuel subsidies, 10 billion SYP ($20 million USD) for the ‘agricultural production funds’, and 10 billion SYP ($20 million USD) for social assistance. The 2019 budget also allocates 1.1 trillion SYP ($2.21 billion USD) for investment, and a total of $50 billion SYP ($100 million USD) for reconstruction and job opportunities. Yet, the 2019 budget did not allocate any funding for public sector wage increases, nor did the budget allocate funding to areas outside of direct Government of Syria control, namely Idleb governorate, Hasakeh governorate, SDF-controlled Deir-ez-Zor governorate on the east bank of the Euphrates River, rural Hama and western rural Aleppo. It is also important to note that the budget indicated Government of Syria will only begin to pay accumulated debt beginning in 2034.

Analysis: In large part, the expansionary Syrian budget is an expression of the inflationary pressure facing the Syrian Lira. According to the Government of Syria, the 2019 budget of 3.882 trillion SYP is equal to $8.92 billion (USD). However, the Government of Syria claims that the SYP/USD exchange rate is 435 SYP/USD, while the de-facto rate in most of Government-held is 496 SYP/USD, as of December 12. It is also worth noting that the exchange rate is constantly depreciating; by example, the October 2018 informal exchange rate was 465 SYP/USD. Therefore, the more realistic 2019 budget is closer to $7.8 billion USD, and this number will certainly decrease as the SYP/USD exchange continues to depreciate.

While the 2019 budget has been hailed as the largest since the start of the conflict, it actually reflects the Government of Syria’s deep financial constraints. For instance, the budget did not allocate any increase in public sector wages, which have already been drastically impacted by the depreciating SYP exchange rate; the importance of public sector wages is illustrated by Jihad Yazigi, who calculates that nearly 90% of Syrians living in Government of Syria-held areas had some form of state employment in 2016. Furthermore, the approximately $100 million USD allocated to reconstruction is dwarfed by the estimated $200-$400 billion USD cost of Syria’s reconstruction – although it is clear that the 2019 budget does not cover the reconstruction of areas outside of Government of Syria control. Most critically, the meager allocation for reconstruction funding necessitates foreign investment in reconstruction projects, which will only solidify Syria’s allies political and economic influence over the country, especially considering the delayed debt repayment plan. Notably, the Governments of Russia and Iran have both invested in infrastructure and natural resource production, and their economic influence will likely increase dramatically in Syria’s internal affairs and foreign policy.

HTS Withdraws from Morek Offices

Morek, Northern Hama Governorate, Syria: On December 7, Hay’at Tahrir Al-Sham-affiliated combatants reportedly withdrew from offices at the Morek crossing point in northern Hama to unknown destinations in Idleb governorate. The withdrawal of Hay’at Tahrir Al-Sham from Morek was concurrent with the reported deployment of Iranian combatants and proxy groups in the vicinity of Morek, along the nearby highway linking Hama city to Muharda in western rural Hama. Notably, continuous media reports have indicated Iran’s armed presence in western rural Hama in areas close to the disarmament zone for approximately the past two months. However, on December 9 Government of Syria military sources indicated to Syrian media outlets that a Government of Syria offensive on opposition-controlled northwestern Syria is to occur in the near-term, and that the offensive will eventually lead to the separation of northwestern Syria into five separate pockets, each of which to be reconciled individually

Analysis: Morek is one of the most vital and profitable cross-line points in northwestern Syria, and Hay’at Tahrir Al-Sham would be unlikely to abandon it without cause. However, the specific reason behind Hay’at Tahrir Al-Sham’s evacuation from the Morek crossing remains unclear. Hay’at Tahrir Al-Sham’s withdrawal could be regarded as indication that Hay’at Tahrir Al-Sham has succumbed to diplomatic pressure from the Government of Turkey, and is taking steps to follow the terms of the disarmament zone agreement. However, in light of reported Iranian military deployments, as well as weekly indications of increased Government of Syria military deployments, the withdrawal of Hay’at Tahrir Al-Sham could equally be registered as anticipation for an impending Government of Syria offensive. Public statements following the Astana 11 talks, held on November 28 and 29, reiterated that the governments of Turkey and Russia remain committed to the disarmament zone agreement; however, the potential Government of Syria offensive cannot be discounted and is indeed increasingly likely, considering the recent reports of Government of Syria military deployments.

Salvation Government Reshuffling

Bab Elhawa, Idleb Governorate, Northwestern Syria: On December 10, the Salvation Government Constitution Drafting Assembly convened a general conference at Bab Elhawa in northern Idleb governorate to approve the new Salvation Government ministerial appointments and to appoint Fawwaz Hilal as its new Prime Minister. Local sources indicated that Hilal, as well as most of the newly appointed ministers, are known for their close affiliation with Hay’at Tahrir Al-Sham. The general conference also reduced of the number of Salvation Government ministries by two, merging the Ministries of Economy and Agriculture and the Ministries of Housing and Reconstruction with Local Administration and Services. It is important to note that one of the reasons given for the reshuffling of the Salvation Government ministries was that the Salvation Government’s Prime Minister, Mohamad Al-Sheikh, had resigned; Mohamad Al-Sheikh has previously submitted two resignation letters that were rejected over the past year.

Analysis: According to local sources, Mohamad Al-Sheikh and several other Salvation Government ministers have been dissatisfied with Hay’at Tahrir Al-Sham’s inability to fulfill its financial pledges to the Salvation Government since its creation in November 2017. Indeed, the Salvation Government does suffer from funding shortages, which has reportedly impacted local administration and service provision, according to local sources. As such, Hay’at Tahrir Al-Sham has most likely chosen to implement the changes in the Salvation Government for two reasons; first, in an attempt to ‘refresh’ the image, reputation, and mandate of the Salvation Government by effectively creating a new government; and second, by merging ministries with existing means of revenue-generation to allow for greater flexibility in the aggregation and allocation of funding.

Assassinations of Reconciled Commanders

Da’el and Mzeireb, Dar’a Governorate, Southern Syria: On December 9, Mashour Kanakri, the Head of the Da’el Reconciliation Committee, western Dar’a Governorate, was assassinated in Da’el; those responsible for the Kanakri’s assassination are unknown. Notably, Kanakri was a key figure in the reconciliation of armed opposition groups in Da’el; Kanakri had previously led the Southern Front’s Liwa’ Moujahidi Horan, reconciled with the Government of Russia during the southern Syria offensive in June 2018, and gone on to join the Government of Syria’s Military Security Branch. An anonymous statement was circulated on social media December 10, accusing the ‘Popular Resistance’ in Dar’a governorate of responsibility; however, on the same day, the Popular Resistance denied their responsibility for the assassination. On December 11, Yousef Muhamad Hashish, a second reconciled armed opposition commander, was also assassinated in Mzeireb. Following his reconciliation in June 2018, Hashish also joined the Government of Syria Military Security Branch. Of note, the ‘Popular Resistance’ was reportedly formed on November 15, 2018 and is believed to be comprised of armed opposition group members in Dar’a governorate who refused to evacuate to northwestern Syria in July 2018 following the conclusion of the Government of Syria’s southern Syria offensive.

Analysis: These assassinations speak to the unstable socio-political and security environment in recently reconciled communities, as well as the specific challenges facing reconciled armed opposition combatants in southern Syria. Instability in the region is unlikely to resolve itself in the near term nd similar dynamics will likely continue in all reconciled areas for the foreseeable future. Although no actor has claimed responsibility for the assassinations, detentions and assassinations of reconciled former opposition commanders are common in post-reconciled areas, particularly in southern Syria. Local sources reported that Mashhour Kanakari had close ties with the head of the Military Security Branch in Dar’a governorate, Louay Ali; however, they also noted that Kanakri was closely linked to Russian reconciliation efforts in southern Syria. Furthermore, it is unclear what specific affiliations and relationships Yousef Hashish maintained. There are certainly tensions between commanders who reconciled under the aegis of the Government of Russia and commanders who were more closely linked to Government of Syria reconciliation efforts; consequently, it is as likely that Kanakri was assassinated by disgruntled former armed opposition groups as by Government of Syria forces.

The Wartime and Post-Conflict Syria project (WPCS) is funded by the European Union and implemented through a partnership between the European University Institute (Middle East Directions Programme) and the Center for Operational Analysis and Research (COAR). WPCS will provide operational and strategic analysis to policymakers and programmers concerning prospects, challenges, trends, and policy options with respect to a conflict and post-conflict Syria. WPCS also aims to stimulate new approaches and policy responses to the Syrian conflict through a regular dialogue between researchers, policymakers and donors, and implementers, as well as to build a new network of Syrian researchers that will contribute to research informing international policy and practice related to their country.

The content compiled and presented by COAR is by no means exhaustive and does not reflect COAR’s formal position, political or otherwise, on the aforementioned topics. The information, assessments, and analysis provided by COAR are only to inform humanitarian and development programs and policy. While this publication was produced with the financial support of the European Union, its contents are the sole responsibility of COAR Global LTD, and do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Union.