Syria Update

13 June to 19 June, 2019

The Syria Update is divided into two sections. The first section provides an in-depth analysis of key issues and dynamics related to wartime and post-conflict Syria. The second section provides a comprehensive whole of Syria review, detailing events and incidents, and analysis of their respective significance.

The following is a brief synopsis of the in-depth analysis section this week:

The U.S. Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) designated sixteen individuals and entities associated with what it described as “an international network benefiting the Assad regime” on June 11. The principal targets of these sanctions are assets under the direct or indirect control of Syrian oligarch Samer Foz, and will impact important businesses in key sectors of the Syrian economy, including oil, food, transport, and trade. Questions will again be asked as to the value and purpose of the sanctions; but they are notable for the fact that Foz has now been targeted by the U.S. government, placing his other, wide-ranging business interests under the spotlight. Of most importance to the aid community will be Foz’s status as a major stakeholder in Al-Baraka Bank Syria (ABBS). ABBS has not been targeted in the recent round of sanctions, but if it were designated by OFAC, the move could have major implications for the aid response undertaken by both international and national organizations. Most INGOs are required to use ABBS as a condition of registration in Syria, and national aid actors that use the bank, such as the Government of Syria-linked Syrian Arab Red Crescent (SARC), are now concerned about potential asset freezes. The implications for the response are potentially significant and immediately obvious: SARC, for instance, is a major implementer of ground-level programming on behalf of both the Syrian government and international organizations alike. Were an asset freeze on ABBS to inhibit SARC’s operations, the aid response is likely to experience significant disruption.

The following is a brief synopsis of the Whole of Syria Review:

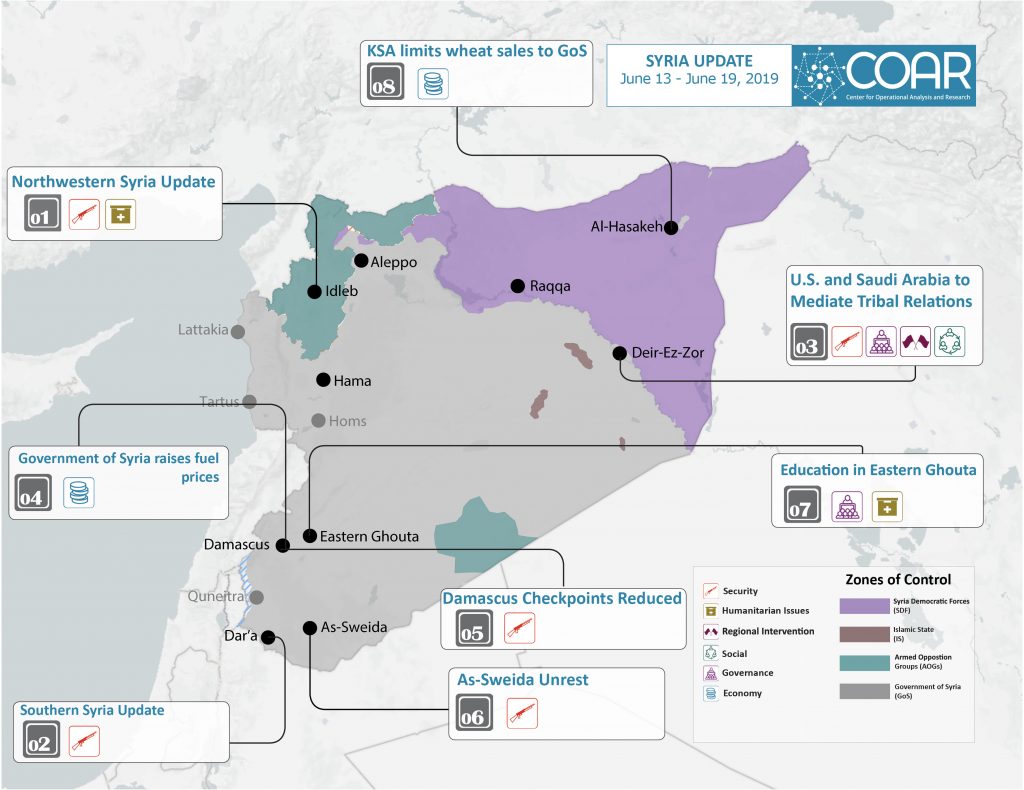

- Turkish and Syrian forces clashed in the most serious escalation between the parties since the beginning of the northwestern offensive; the incident highlights the possibility that Russia will look to bring the Syrian and Turkish governments to the table in an effort to prevent further conflict.

- Violence has continued across Dar’a Governorate; the Government of Syria is expected to persist with its hitherto confrontational approach to controlling local unrest.

- U.S. and Saudi officials engaged tribal leaders in northeastern Syria, while the Kurdish Self-Administration established new military councils in Tal Abyad and Ain Al Arab; both initiatives aim to improve Kurdish-Arab relations but come in the context of continued mistrust.

- Prices of unsubsidized fuel were raised by the Syrian Ministry of Internal Trade and Consumer Protection, but pricing remains beyond the full control of the central authorities.

- Eight checkpoints were reportedly dismantled on the periphery of Damascus, reportedly as part of a checkpoint reconfiguration plan that had been delayed due to security concerns in the capital and nearby areas.

- Tit-for-tat kidnappings were reported in As-Sweida city; though tensions produced by these events are expected to be resolved by local religious figures, their mediation is only likely to temporarily alleviate civilian concerns over the mounting interventions of government security forces.

- Schools in Eastern Ghouta were prevented from holding examinations; students are being forced to travel to other locations via checkpoints, giving rise to concern that the Government of Syria seeks to monitor future generations in post-reconciled communities.

- The Kurdish affecting crop harvests across Al-Hasakeh continue, with Government of Syria figures disputing

media accounts about the extent to which land and farmers have been negatively affected.

‘Samer Foz’ Sanctions

In Depth Analysis

On June 11, the U.S. Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) designated sixteen individuals and entities associated with what it described as “an international network benefiting the Assad regime.” The principal targets of these sanctions are assets under the direct or indirect control of Syrian oligarch Samer Foz, who is accused by OFAC of “supporting the murderous Assad regime and building luxury developments on land stolen from those fleeing his brutality.” The sanctions go much further than real estate, however. OFAC has also designated trading, transport, banking, oil, media, and commodity companies run by Foz and his siblings; the effects of these measures will be felt across key sectors of the Syrian economy.

Given their wide-ranging effects, observers will again ask questions as to the ethics of sanctions in conflict-affected contexts. Analysts might also speculate about their efficacy, particularly given that Foz can likely limit his exposure to international financial mechanisms by operating within Syria’s internal economic ecosystems. Others will assume the sanctions have as much to do with U.S. policy on Iran as with Syria: not only is Foz reportedly linked to Tehran, but OFAC also designated dozens of Iranian petrochemical companies last week amid tensions in the Strait of Hormuz. These are valid perspectives that demand consideration. But, for the aid community, their implications are dwarfed by the prospect that sanctions against Foz will be extended to banking services in which he is a major stakeholder.

Samer Foz has emerged as one of Syria’s most prominent business figures almost overnight. A Sunni lawyer from Lattakia, Foz inherited a leading role in the Aman Holding Group (AHG) from its main shareholder and founder, his father, Zahir. Established in 1988, AHG’s pre-war business interests were relatively modest, centering mainly on the distribution of grain, building materials, and aggregates in Syria’s northwest. The company expanded somewhat after securing contracts to import Turkish cement, in 2010, but this deal did not fundamentally alter AHG’s operations and does not explain the massive diversification of AHG’s portfolio since 2015. In only four years, Samer Foz has worked via AHG, its subsidiaries, and a series of new and family-linked entities to invest in or wholly acquire business in foodstuffs, banking, petroleum, airlines, and hotels, as well as flour mills, iron-smelting facilities, and automotive, pharmaceutical, and sugar-processing factories.

Few other business figures have risen to such prominence so quickly without links to the highest echelons of the Syrian government. It is these alleged connections that the OFAC sanctions scrutinize—and not without justification, given Foz’s well-publicized involvement in the Marota City real estate project, which is cited in the OFAC release. Foz, however, is not only a lynchpin in the delivery of the regime’s post-conflict economic agenda. Shortly before the European Union issued restrictive measures against a number of Syrian government-affiliated entities and individuals in January 2019, Foz became a major stakeholder in the two largest banks in Syria, the Syria International Islamic Bank (SIIB) and Al-Baraka Bank Syria (ABBS). Critically, ABBS accounts for a significant proportion of funds held and processed on behalf of major national and international aid organizations in Syria, making the bank an indispensable part of the Damascus-based humanitarian and development response.

SIIB has been sanctioned by OFAC since 2012, and it largely handles transactions on behalf of relatively small local organizations. However, INGOs, government-linked aid organizations, and smaller local organizations alike use ABBS. Use of ABBS was reportedly a requirement of registration with the Syrian authorities for both DRC and NRC, and likely for many other international agencies. The UN (and its Damascus-based staff) similarly uses ABBS, in part because it is linked to Gulf-based companies, which makes it one of the few institutions in Syria capable of handling regional transactions. Notably, ABBS was not specifically sanctioned in the recent round of Department of the Treasury designations. However, it was mentioned in OFAC’s sanctions release on Samer Foz, and has therefore raised fears that it will be sanctioned in the future. If ABBS were to be sanctioned, international agencies could appeal to OFAC for licenses to continue their Syria-based operations; however, the work of Syrian NGOs required to use ABBS would likely be severely disrupted.

The government-affiliated SARC and Syria Trust are two actors that would likely be deeply affected by potential sanctions on ABBS, as both reportedly have the large majority of their accounts in ABBS. Given that national NGOs linked to the Syrian government are major ground-level partners for international aid actors—not to mention the main vehicles for the delivery of aid and relief in government-held areas—sanctions targeting ABBS could effectively freeze the assets under the control of organizations undertaking the bulk of project implementation in Syria. The potential impact of sanctions against ABBS cannot be overstated: if the bank is designated and its connections to the international financial system effectively severed, much of the aid response could face a critical capacity shortfall, placing an even greater burden on the already challenging Syria response.

Whole of Syria Review

1. Northwestern Syria Update

Idleb, Hama, and Aleppo governorates, Syria: On June 13, the Russian Reconciliation Center announced that Russia and Turkey had brokered a ceasefire between Government of Syria forces and the National Liberation Front (NLF) in northwestern Syria. Notably, the NLF denied it had been informed of any such agreement. Shortly after news of the ceasefire broke, the Government of Syria targeted several areas in western rural Hama Governorate, including a medical clinic near the 10th Turkish observation point, in Shir Mghar. Three Turkish soldiers were injured in this incident. On June 14, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan stated in a press conference that Turkey will not remain silent and “will do what is necessary” should another attack occur in the vicinity of Turkish observation points in future. Indeed, on June 16, shelling by Government of Syria forces on another Turkish observation point, in Murak, was immediately followed by retaliatory Turkish fire on a Government of Syria checkpoint in Tal Barzan. Turkish Special Forces Command units were subsequently sent to Hatay. Following this escalation, Syrian Minister of Foreign Affairs Walid Muallem stated in a press conference that the Government of Syria does not intend to clash with Turkish forces in the area. Meanwhile, between June 16 and June 18, a decrease in the intensity of aerial bombardment, airstrikes, and shelling was observed on frontlines in Kafr Hud and Tayr Jamlah. Attacks have since reportedly resumed, and, on June 18, the Fateh Moubin Operations Room launched another phase of its ongoing counteroffensive against Syrian government forces in the same area. The Fateh Moubin Operations Room is comprised of the NLF, Hay’at Tahrir Al-Sham, and Jaish Izza.

Analysis: Direct confrontation between the Syrian and Turkish governments in northwestern Syria, specifically the incident in which Turkish soldiers were injured, is the most serious escalation between the parties since the beginning of the Syrian government-led offensive on northwestern Syria. The Turkish response so far has been firm and likely sufficient to prompt the intervention of the Russian government, both to resume negotiations with its Turkish counterpart and to prevent an escalation between Syrian and Turkish forces. What is clear, however, is that the situation in the northwest increasingly appears to be reaching a point at which Russian, Syrian, and Turkish interests will converge and compete on active frontlines rather than in the conference room alone. Some form of agreement thus becomes more probable, but so, too, does the prospect of further incidents between the various parties resulting in escalation. Should discussion produce a formal agreement, its content is currently hard to predict, especially as Turkey has demonstrated little interest in surrendering northern rural Hama to Government of Syria forces. Uncertainty surrounding the future of Tal Refaat likely plays into Turkish thinking in this regard, but, again, the issue of Kurdish-controlled areas like Tal Refaat is far from being concluded. In the meantime, the Government of Syria’s apparent disregard for last week’s reported ceasefire demonstrates that it intends to pursue its objectives to secure the M5 highway and Jisr Al-Shugour. Further displacement and a growing civilian death toll is, therefore, highly likely.

2. Southern Syria Update

Dar’a Governorate, Syria: Explosions, assassinations, and detentions have continued across Dar’a Governorate over the past week. On June 12, media outlets and local sources reported on artillery fire against a Government of Syria Air Force Intelligence checkpoint in which several were killed and injured. On June 16, local sources reported an explosion at the Hrak subdistrict municipal headquarters; no deaths or injuries were reported in this incident. These local sources noted that the Government of Syria had rehabilitated the building and intends to use it as a base to police the city. Also, on June 15, opposition affiliates from As-Sanamayn detained three Government of Syria combatants on the Damascus-Dar’a highway in response to the imprisonment of three individuals over the past month. This prompted Government of Syria forces to detain two former opposition commanders, on the road linking Tasil to Bakkar, in western rural Dar’a, and conduct a detention campaign in Tasil. Notably, local sources report that government forces prohibit governorate residents from organizing funerals for combatants who have died during the current military offensive in northwestern Syria. As highlighted in previous COAR Syria Updates, communities in Dar’a strongly oppose the deployment of reconciled fighters from Dar’a on the frontlines in Hama Governorate. Indeed, some have defected from government forces to avoid deployment to this location.

Analysis: The Government of Syria has yet to extend its arrangement with the Dar’a negotiation committee, even though the existing reconciliation agreement has now expired. That said, this agreement has so far failed to bring about the smooth introduction of government political and military structures. To a great extent, this failure is likely due to the ongoing government-led offensive in northwestern Syria, which has diverted much of the government’s attention, although it is also symptomatic of the increasingly bold activities of local opposition groups. Local reports further note that the growing role and presence of Iran-affiliated militias has weakened the capacity of the Syrian government to control the situation, as these militias function beyond the command of the Syrian military authorities. Unable to address the situation, and needing to maintain order along its borders with Israel and Jordan, the Government of Syria has resorted to taking a confrontational approach toward restive local communities. A conciliatory approach from the Government of Syria is improbable over the near to medium term, meaning the local security situation is likely to become more volatile.

3. U.S. and Saudi Arabia to Mediate Tribal Relations

Deir-ez-Zor Governorate: On June 13, the deputy assistant secretary for House affairs in the U.S. State Department’s Bureau of Legislative Affairs, Joel Rubin; the chief adviser to the international coalition forces for fighting IS in Syria, William Robak; and Saudi state minister for Gulf affairs, Thamer Sabhan, visited Omar oil field in Deir-ez-Zor Governorate. The officials held a closed meeting with commanders of the Kurdish Self-Administration’s (KSA) Executive Council, as well as a meeting with local tribal leaders and notables. Sabhan reportedly declared Saudi Arabia’s willingness to assist in the rehabilitation of communities, provided that tribes maintain good relationships with the KSA and refrain from deepening relations with the Turkish and Qatari governments. Local sources noted that Robak visited Ein Issa; during this visit, he reportedly reiterated U.S. support for the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) and discussed the prospect of suing ISIS combatants in international court. On June 16, media sources indicated that the KSA had announced a new military council in Tal Abyad and Ein El Arab. This council reportedly intends to enhance the capacity for self-defense in local communities and to increase community participation in local governance decision-making. Local sources add that the new councils intend to demonstrate the independence of local Kurdish governance processes from the PYD and the KSA’s central leadership in Al-Hasakeh and Quamishli. In addition, local sources report that the KSA has also announced the establishment of an investigative committee to fight corruption in military councils in Self-Administration-controlled areas.

Analysis: Attempts by the KSA and the SDF to enhance their reputation in areas under their control are unlikely to shift the widespread public perception that they are instruments of an exclusively Kurdish national project. They have been frequently accused of sidelining local notables throughout the course of the Syrian conflict, meaning local Arab populations are likely to be suspicious of the initiatives described above. The intervention of Saudi Arabia may smooth local tensions given that many locals are linked, by virtue of extended tribal formations, to both Saudi Arabia and the Gulf. However, it is important to remember that the political positions of tribes are hard to predict and often contingent on material gain. Saudi Arabia’s ability to shift tribal political affiliations will therefore rest largely on its willingness to invest in local improvements that better the lot of local tribal populations. In this regard, it is notable that Saudi Arabia stepped in to financially support the SDF in August 2018 following reductions in U.S. funding. Yet, even if such efforts are effectively pursued by the U.S. and Saudi Arabia, the extent to which these actors can ease deep-seated Arab-Kurdish tensions remains questionable.

4. Government of Syria raises fuel prices

Damascus, Syria: On June 15, the Government of Syria’s Ministry of Internal Trade and Consumer Protection issued a decree stipulating an increase in the price of unsubsidized fuel suitable for most private vehicle use. Prices for unsubsidized fuel have subsequently increased from SYP 375 to 425 per liter. Premium quality fuel prices decreased from SYP 600 to 550. Subsidized fuel prices remain the same. Upon issuing the decree, Minister of Trade Atef Al-Nadaf reportedly stated that the price of unsubsidized fuel would be reviewed and changed on a monthly basis, in accordance with the global market.

Analysis: Fuel price changes will necessarily affect practically all forms of national production and increase the cost of living, particularly in government-held areas. Prior to the war, the Government of Syria subsidized all fuel. However, restricted access to foreign oil imports, the loss of oilfields to its rivals, and much diminished national production has placed subsidy initiatives under considerable strain. As frequently reported in previous COAR Syria Updates, strategies so far adopted by the Government of Syria to mitigate the fuel crisis have been largely unsuccessful. The situation has worsened in the past week after dozens of Iranian petrochemical companies were sanctioned by OFAC on June 11, not to mention OFAC’s similar designation of two Lebanon-based oil trading companies owned by Samer Foz on June 13. For the time being, fuel price regulation remains outside the full control of central authorities, increasing the prevalence of black-market rates, trading, and monopolization by private actors.

5. Damascus Checkpoints Reduced

Damascus, Syria: On June 18, it was reported that the Government of Syria had dismantled eight checkpoints in recent months, each of which was located on the periphery of Damascus city. Reports on the matter cited Rural Damascus Governor Alaa Ibrahim stating that plans to streamline checkpoint numbers have been under consideration for some time, but have been delayed for security reasons. These plans also reportedly aim to reduce the number of checkpoints on key roads linking Damascus with nearby areas. No information on these areas under consideration is currently available.

Analysis: It must be noted that there are few sources reporting on this development, which, if true, would mark a small step towards the desecuritization of Damascus and its neighboring areas. Moreover, given the limited information, there are multiple ways in which plans to reduce checkpoints could be interpreted. Last week, the Syria Update described the removal of several checkpoints under the control of Iran- and Iraq-affiliated militia in Damascus, as well as a reduction in the number of foreign troops in the city. Reported plans to reduce the number of checkpoints could be linked to the government’s progress on its political-security objectives in Rural Damascus Governorate. Certainly, there are still numerous security-based restrictions in place in locations such as Eastern Ghouta and southern Damascus, but both areas have been under government control for well over a year now, and detentions and arrests have declined over this time. The extent of the checkpoint plan remains to be seen, but, should a pattern emerge, it will likely indicate the Government of Syria’s security priorities in reconciled areas on Damascus’s periphery.

6. As-Sweida Unrest

As-Sweida city, As-Sweida Governorate, Syria: Local media sources and social media describe a growing state of alert in As-Sweida city following a series of detentions allegedly undertaken by both local factions and Government of Syria forces. On June 17, media sources reported that local factions had accused Government of Syria Military Security of kidnapping Mohamad Shihabeddine, a local activist known for his opposition to the Syrian government. Military Security has reportedly denied its involvement in the incident. In response, the local group to which Shihabeddine is affiliated, Shouyoukh Al-Karama, clashed with government forces and detained several government-affiliated combatants. In addition, two Air Force Intelligence generals were kidnapped on the As-Sweida-Damascus highway. The identity of those responsible for this latter incident remains unknown, and it is unclear whether this incident is related to those mentioned above.

Analysis: Kidnappings, detentions, and occasional clashes have increased in frequency in As-Sweida Governorate in recent months, and these incidents are likely to add to tensions between the resident population and Government of Syria security forces. For the time being, the Government of Syria will likely appeal to local religious leaders—namely, Shouyoukh Al-Aqel—to prevent an escalation. However, this is only likely to secure temporary reconciliation between belligerents. As-Sweida residents are generally hostile to attempts by the Government of Syria to strengthen its military and political authority, and efforts to do so have commonly been rebuffed. But the detention of As-Sweida locals by government-linked forces indicates that government-affiliated security actors are willing to forcefully pursue their objectives in the area, meaning further such incidents are probable.

7. Education in Eastern Ghouta

Eastern Ghouta, Rural Damascus: On June 15, media sources reported that the Government of Syria’s Ministry of Education had refused to open schools in Eastern Ghouta as testing centers for students, citing security concerns. Students in central parts of Eastern Ghouta were obliged to travel to alternative testing centers in Jaramana, requiring their transit through multiple checkpoints and security screening procedures. Examinations have thus been delayed, and there is reportedly concern among student populations over the prospect of detention at checkpoints. Teachers in Eastern Ghouta claim that schools in the area are capable of holding the examinations and that the closure of schools during the examination period was a punitive measure. Sources reporting on this development note that security approval is required to open testing centers.

Analysis: Since securing control of Eastern Ghouta, the Government of Syria has made little effort to rehabilitate communities, let alone to a standard commensurate with the expectations of local civilians. The continuation of this situation, in addition to the persistence of restrictions on the free movement of people, indicates that the government retains major post-reconciliation political and security objectives in the area. Although targeting schools, as the teachers claim it is doing, may not appear to immediately fulfil these objectives, the measure could be linked to the government’s interest in monitoring Eastern Ghouta’s population, specifically its future generations. Other reconciled areas with a previously pro-opposition population may therefore witness the application of similar strategies.

8. KSA limits wheat sales to GoS

Raqqa, Deir-ez-Zor, Al-Hasakeh Governorate, Syria: On June 12, media sources cited Salman Barado, Head of the region’s economy and agricultural board, as stating that the KSA will ban the transfer of wheat to Government of Syria-controlled areas. Badran Jia Kurd, a Kurdish official, indicated that the decision aims at securing a reserve of wheat for two years for local consumption, and should not be regarded as a “political decision to impose siege on Damascus.” Of note, Barado specified that local producers will be permitted to trade with government-held areas, and the restriction applies only to larger traders and state workers. This year the Government of Syria has set a higher price for the purchase of wheat from farmers than that assigned by KSA – a decision that Jian Kurd framed as an attempt to cause a schism between the administration and local farmers. Meanwhile, fires on agricultural land across northeastern Syria have continued. On June 16, the Self-Administration reportedly stated that 50 hectares of such land had caught fire in Ein El Arab and an estimated 40 percent of agricultural lands had been destroyed prior to the harvest period. The Ministry of Agriculture stated that the amount of land affected by the fires since they began, in late May, is 50,268 hectares. In this release, the ministry stated that it considered the loss of land to be small relative to the total amount of cultivated land in the country.

Analysis: The decision of the KSA to limit the supply of large amounts of wheat and grain to Government of Syria-held areas is expected to increase the pressure on the government to secure alternative supplies. Indeed, the Syrian government reportedly bought as much as 40% of the entire wheat crop produced in KSA-administered areas in 2018. Presently, however, the Government of Syria is subject to an ever tightening sanctions regime which inhibits its ability to import essential goods. Though no restrictions are in place on the Syrian government’s import of wheat, banking sanctions and asset freezes make it more difficult to do so. A Memorandum of Understanding is in place with the Russian government for the import wheat from Crimea, a deal which is expected to deliver around 1.5 million tonnes over its lifetime. But, combined with the degradation of northeastern Syria’s agricultural lands, both as a result of poor maintenance and recent local fires, the bread subsidies to which the Syrian government is committed will place an ever increasing strain on public finances.

The Wartime and Post-Conflict Syria project (WPCS) is funded by the European Union and implemented through a partnership between the European University Institute (Middle East Directions Programme) and the Center for Operational Analysis and Research (COAR). WPCS will provide operational and strategic analysis to policymakers and programmers concerning prospects, challenges, trends, and policy options with respect to a conflict and post-conflict Syria. WPCS also aims to stimulate new approaches and policy responses to the Syrian conflict through a regular dialogue between researchers, policymakers and donors, and implementers, as well as to build a new network of Syrian researchers that will contribute to research informing international policy and practice related to their country.

The content compiled and presented by COAR is by no means exhaustive and does not reflect COAR’s formal position, political or otherwise, on the aforementioned topics. The information, assessments, and analysis provided by COAR are only to inform humanitarian and development programs and policy. While this publication was produced with the financial support of the European Union, its contents are the sole responsibility of COAR Global LTD, and do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Union.