Syria Update

30 March 2020

Table Of Contents

Download PDF Version

Beyond the health sector: COVID-19’s impact on Syria’s economy and detainees

In Depth Analysis

Following weeks of half-measure responses to the COVID-19 pandemic, authorities in every region of Syria have rapidly tightened restrictions to lessen the anticipated burden on the country’s fractured and exhausted health care systems. The situation continues to develop rapidly, as the first confirmed COVID-19 death has been reported, and additional suspected cases emerge by the day. Thus far, much of the international Syria response has focused on Syria’s medical infrastructure, in particular its overall capacity to handle the looming crisis. Early indicators are troubling. Most notably, of the estimated 325 intensive-care unit beds and respirators in Syria, 203 are located in the Government of Syria strongholds of Damascus, Lattakia, and Tartous governorates. Dar’a governorate has three such beds. Deir-ez-Zor has none.

Syria’s political geography will factor in the COVID-19 crisis. Without doubt, even ‘useful Syria’ — the Government’s priority areas loosely defined as the M5 corridor and the predominantly Alawi coast — will likely struggle to meet emerging needs. Northeast and northwest Syria will face even greater challenges, including large-scale displacement, crowded camps, shattered infrastructure, long-standing developmental neglect, and limited health system capacity (see: Syria Update 23 March). However, when compared to Government-held areas, these regions also have a greater presence of local civil society organizations, which may be among the best-placed entities to meet urgent response needs. Identifying local actors capable of bringing capacity online both in the near term, and on a longer timescale as the crisis develops, will likely be foremost challenges as the Syria response seeks ways to address COVID-19 in Syria.

However, it is also important to note that — as witnessed elsewhere in the world — the COVID-19 crisis will also have a considerable impact in Syria outside the health sector. Already, the crisis has had a notable impact in two areas: first, on the fragile Syrian economy, and second, on the potential for the release of some of the estimated 130,000 detainees in Government of Syria detention.

Economic Impact

On 24 March, Syrian state media announced that state employee salaries are to be paid out in incremental tranches via ATMs, in an attempt to reduce payday crowding to contain the spread of the coronavirus. The scope of the measure’s implementation is not yet clear; however, it has the potential to delay the salary payments of large portions of the Syrian population. In terms of household economics, the timing could not be worse. On 27 March, the value of the Syrian pound fell to an all-time low against the dollar. In parallel, market prices for basic commodities continue to shoot upward — selling at premiums ranging from 20 to 40 percent. Additionally, media sources report that large numbers of military servicemen and officers are expected to be decommissioned. Meanwhile, the state’s failure to introduce direct relief measures or impose a rent moratorium leaves many already vulnerable Syrians in even greater jeopardy, particularly in the wake of the forced closure of commercial enterprises and other restrictions on income-generating activities.

Without doubt, Syria’s poor have been hit hardest. More than four-fifths of the population is below the poverty line, and protective masks, sanitizers, disinfectants, and medications for underlying maladies are already out of reach for much of the Syrian population — if they are available at all. Stockpiling of essential commodities has been possible only for the relatively wealthy. Moreover, state rationing is now itself a risk to the neediest Syrians, who are often forced to wait in hours-long queues to collect rationed cooking gas, fuel, and other subsidized goods. As of this writing, it is not clear what mechanisms will be implemented to prevent distribution points from becoming sites of viral outbreak. To date, attempts to decentralize the distribution of bread through community focal points have failed, and bread rations have already dwindled in Government areas.

Amnesty

The crisis may also affect Syria’s detainees. On 22 March President Bashar al-Assad announced Legislative Decree No. 6, a general amnesty for convicted criminals and military deserters. In practical terms, the amnesty differs little from previous decrees. The measure has two main effects. First, it reduces prison sentences and criminal penalties for a wide range of crimes committed since 2011. Second, it lifts the penalty for military desertion — granting a grace period of three months for deserters inside the country, and six months for those who are currently abroad.

More notable than the contents of the decree is its timing. In the past, the Government of Syria has announced amnesties to coincide with major national events. For instance, Al-Assad issued a wide-reaching amnesty in 2014 following his re-election to the presidency. More recently, the last general amnesty in late 2019 was widely interpreted as a measure to boost military recruitment ahead of the Government’s military offensive in the northwest (see: Syria Update 12-17 September 2019). As such, it is possible that the decree may be part and parcel of a wider Government of Syria strategy to contain the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic by reducing prison populations. There are good reasons to view this possibility with caution, however. The amnesty is likely to exclude detainees held under ‘anti-terror’ laws. Moreover, there is little precedent for the release of detainees on a large scale, despite the existence of numerous legal pathways to do so. According to the Syrian Network for Human Rights, the Government of Syria has declared 17 legal amnesties since the onset of the popular uprising in 2011; nonetheless, the watchdog organization reports that as many as 130,000 detainees remain in Government detention. As such, if detainees are released in significant numbers under the latest amnesty, it should be seen as a sign that the Government of Syria has been left with no choice but to treat the COVID-19 crisis seriously.

Whole of Syria Review

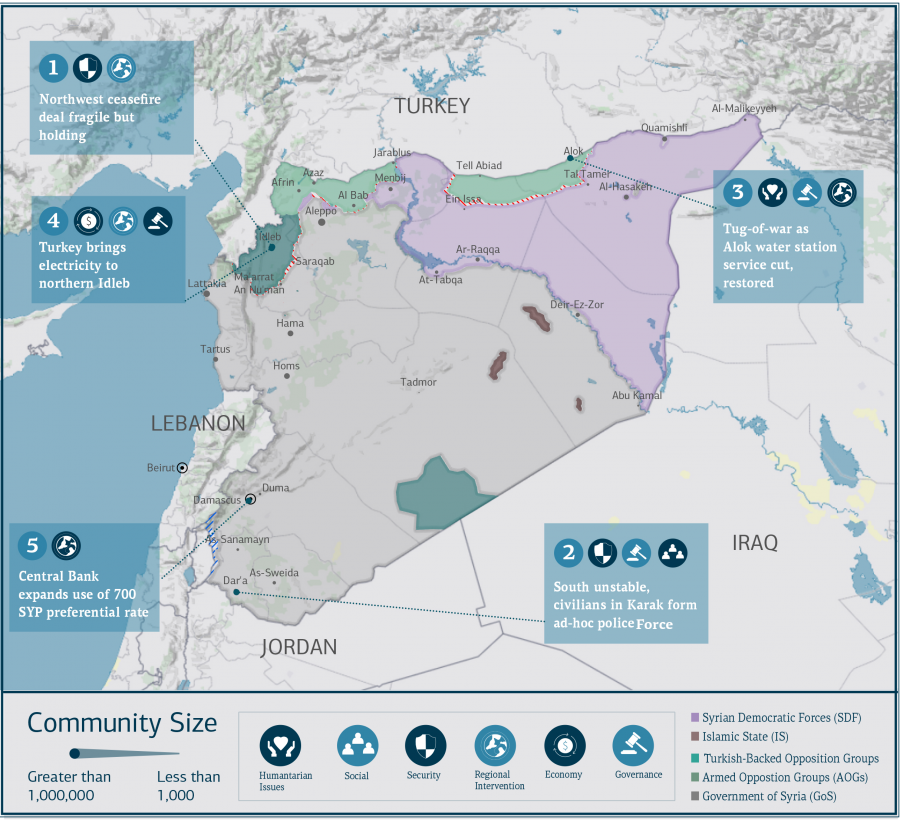

1. Northwest ceasefire deal fragile but holding

Idleb Governorate: On 25 March, media sources reported that Russian Defense Minister Sergey Shoigu made a surprise visit to Damascus to deliver the Government of Syria a clear message concerning Idleb: Moscow will not tolerate any breach of the 5 March ceasefire by Government forces. The reported visit followed several weeks of mounting regional pressure due to the as-yet piecemeal implementation of the joint Turkish-Russian ceasefire plan. To date, the greatest source of friction has been the inability of Russia and Turkey to conduct full, uninterrupted joint military patrols of the M4 highway. Patrols have been stymied by repeated attacks carried out — according to local sources — by members of Hay’at Tahrir Al-Sham and, potentially, Hurras Al Deen. Relatedly, on 26 March, local media reported that Turkish forces have established another observation point along the western end of the zone demarcated for M4 patrols, near Jisr-Ash-Shughur.

Patrols in danger

If reports are accurate, Shoigu’s visit to Damascus will reduce the near-term likelihood that the Government of Syria will resume military operations to open the M4 to commercial traffic. At first blush, this is a welcome development in the wake of rising threats by the Government of Syria, which maintains that it has been left with no choice but to open the road itself. In terms of reducing tensions, it is additionally promising that Russia has publicly downplayed Turkey’s culpability for the failure of joint patrols to take place along the full extent of the planned M4 security corridor. In fact, this failure is the direct result of Turkey’s inability to rein in local extremist groups. Notably, Russia’s deference reciprocates Turkey’s own abnegation of Russian responsibility for the killing of at least 33 Turkish soldiers in a single attack during the northwest Syria offensive in February (see: Syria Update 2 March).

Overall, these developments may be a signal that, for the time being, both Russia and Turkey see the Idleb agreement as well-worth salvaging, despite the intransigence of the local actors that each is ostensibly responsible for bringing into compliance. However, in the longer term, additional threats to the deal may be difficult to contain. The terms of commercial access to the M4 have not yet been resolved. More importantly, it remains to be seen how COVID-19 will impact the highly vulnerable populations of northern Idleb. There is a possibility that a viral epidemic among the displaced populations in northwest Syria will be a rallying cry for armed actors who remain committed to upending the ceasefire arrangement. Finally, there remains a possibility that the Government of Syria itself will see the pandemic as opening a window of opportunity to launch military activities to open the M4 itself.

2. South unstable, civilians in Karak form ad-hoc police force

Dar’a governorate: According to local sources, on 25 March at least 40 residents of eastern Karak established the ‘Popular Civil Movement’, an ad-hoc local police force aimed at stabilizing the security environment in the community. According to a statement released by the group, it will establish multiple checkpoints in Karak and dedicate four hotlines for locals to report security incidents or suspected individuals. Local sources indicated that the group has received some financial support from local businessmen but is currently not affiliated with any armed actors in Dar’a governorate.

Meanwhile, the general security situation across southern Syria remains fluid. Kidnappings and targeted killings continue to be reported on a consistent basis, and clashes between Government of Syria forces and armed opposition combatants also continue. On 18 March, local sources reported that opposition-affiliated combatants and Government of Syria forces clashed on the Jlein-Sheikh Saed road in western rural Dar’a, prompting Government forces to shell the area and the outskirts of Tafas. The clash reportedly killed eight civilians and injured six others. Multiple families displaced from the area to Tal Shhab and the Yarmouk Basin, due to fear of further escalation.

Back to square one

The formation of new local security forces in Karak is a reflection of the security challenges that continue to plague southern Syria. The long-term viability and ultimate efficiency of the establishment are difficult to gauge. It is possible that the Government of Syria and other local security actors will view the local police force as an inherent threat, and thus may seek to nip it in the bud. However, it is also possible that the group’s apparent transparency, base of popular local support, and potentially positive impact will grant it the cover needed to carry out a collective good in securing the community.

The apparent need for such a group is evidenced by the ongoing confrontations between opposition-linked combatants and Government of Syria forces elsewhere in southern Syria. Following the rapid assault of As-Sanamayn in February, the community’s swift reconciliation ignited a chain reaction of similar reconciliation negotiations in communities across southern Syria (see: Syria Update 2 March). Despite their initial promise, these negotiations appear to have faltered. As a result, escalation and an outbreak of attacks on a wider basis remain a distinct possibility, as Government forces and opposition-linked combatants are likely to find reason to turn up the heat and pressure the other for the foreseeable future.

3. Tug-of-war as Alok water station service cut, restored

Alok, Al-Hasakeh: On 27 March, service was restored at the Alok water station as a result of Russian mediation, thus ending a service outage imposed by Turkish forces from 21-26 March. Turkey and Russia reportedly conducted a joint patrol in the area following the resumption of service. Notably, the Alok water station has been a frequent target of Turkish forces. Since the launch of Operation Peace Spring in October 2019, water service at Alok has repeatedly been cut-off by Turkish forces, apparently in a bid to gain leverage over the Self Administration by drying up water service to the northeast Syria communities that are reliant upon Alok. Relatedly, local sources indicate that Russia has offered to lend technical support to the Government of Syria to dig 30 new wells in Hemmeh, west of Hasakeh city, potentially shielding the area against further water shutoffs. Relatedly, on 25 March, the Self Administration also announced its intention to dig new wells; however, it is unclear if this refers to the same initiative announced by Russia.

Deus ex Russia?

Alok water station has been a frequent site of contest between Turkey and Self Administration. What is novel is Russia’s apparently increased willingness to step-in as a guarantor of the Self Administration. Previously, Russia led negotiations with Turkish forces to ensure the uninterrupted supply of water to Al-Hasakeh, in return for a steady flow of electricity to Ras Al Ain, which is under Turkey’s control in the Peace Spring area (see: Syria Update 4-10 December 2019). The evident break-down of the water-for-electricity agreement may help to explain Russia’s continuing efforts to curry favor with the Syrian Democratic Forces. That relationship may be a source of significant leverage vis-à-vis Turkey in the northeast and elsewhere in Syria — and it may be of strategic value in fostering detente between the Self Administration and the Government of Syria. To that end, local reports indicate that Russia has established a permanent base in Al-Hasakeh city, which may be a further source of entrenched presence in the northeast on multiple fronts: military, service, and governance. That is a long-term consideration. In the near term, the issue of greatest concern remains the water supply to Al-Hasakeh. With access to water being among the keys to fighting the spread of COVID-19, that issue is more urgent now than ever.

4. Turkey brings electricity to northern Idleb

Idleb Governorate: On 24 March, the Salvation Government’s General Electricity Establishment reached an agreement with a private Turkish company to bring electricity to Idleb city and its surroundings. According to local sources, work is already underway to link the areas to the Turkish electric grid, and A’zaz has already been supplied with electricity. The grid, once completed, should supply electricity to Harim, and Al Bab as well. Local sources indicated that the power is being supplied from power plants in Turkey and being channeled into Syria. Reportedly, the project is expected to take approximately three months before all the regions specified under the electricity deal will come fully online.

Turkish power, entrenched

The expansive electricity project in northern Idleb is another signal that Turkey has no intention of giving up on Idleb any time soon (or, if it does, to exact a heavy price). Notably, this project follows the extension of Turkish cellular phone networks into the same area earlier this month (see: Syria Update 23 March). That move was seen as an indicator of Turkey’s intention to tighten its grip on northern Idleb through the expansion of service networks, administrative entities, and security coverage, much as it has done in northern Aleppo and northeast Syria. In terms of technical complexity, capital investment, and actual infrastructure, the electrical grid is likely Turkey’s most considerable non-military investment in northern Idleb to date. Thus far, the Government of Syria has had little choice but to accept these gambits. However, the situation in northwest Syria is uniquely volatile. For now, Russia has insisted that the terms of the ceasefire not be violated. The current public health emergency presented by COVID-19 may force the Government to abide by that diktat for the near term.

5. Central Bank expands use of 700 SYP preferential rate

Damascus: On 26 March, the Central Bank of Syria announced that the 700 SYP/USD ‘preferential’ conversion rate would be expanded for use in all transactions inside Syria. The decision carved out an exception for two vital import entities — Syria for Trade and the General Directorate of External Trade — which will continue to purchase imported goods at a rate of 438 to artificially deflate the price of imported goods. Notably, this follows an earlier decision in which the Central Bank set a preferential rate of 700 for international and UN agencies only. Meanwhile, the real exchange rate of the SYP continued to deteriorate, reportedly reaching an unprecedented rate of 1,220 SYP/USD on 27 March.

Keeping liquidity in the market

Faced with continuing depreciation of the SYP and the shutdown of markets due to COVID-19, the Central Bank’s decision to universalize the preferential conversion rate likely aims to ensure the continuity of imports and liquidity in the market. This decision continues the bank’s earlier efforts to facilitate the flow of foreign currency and imports, embodied by its 6 February decision to adopt the 700 SYP/USD rate for remittances transferred via international exchange agencies, while introducing an expanded list of items to be imported at the same rate (see: Syria Update 17 February). In practice, the latest measure will likely mitigate some of the impacts of more recent punitive measures intended to control the money supply by penalizing the use of foreign currencies (see: Syria Update 27 January). While predominantly aimed at centralizing foreign currency under the auspices of the Central Bank, these measures have also impinged upon money transfers and introduced friction to the import process, thereby decreasing liquidity and driving up prices, while creating shortages of key imports. Setting the universal conversion rate at 700 SYP/USD may prompt a short-lived increase in money transfers to the country, but its efficacy in controlling the prices of imported goods is dubious.

Key Readings

The Open Source Annex highlights key media reports, research, and primary documents that are not examined in the Syria Update. For a continuously updated collection of such records, searchable by geography, theme, and conflict actor, and curated to meet the needs of decision-makers, please see COAR’s comprehensive online search platform, Alexandrina, at the link below.

Note: These records are solely the responsibility of their creators. COAR does not necessarily endorse — or confirm — the viewpoints expressed by these sources.

COVID-19 Pandemic: Syria’s Response and Healthcare Capacity

What Does it Say? Among a wealth of preliminary findings concerning the outbreak of the novel coronavirus, the authors posit that Syria’s health system capacity will be exceeded when the total number of COVID-19 cases reaches 6,500 in the country.

Reading Between the Lines: The article is the best overview of Syria’s experience with COVID-19 to date, and it lays out in a clear — and alarming way — the limitations of Syria’s health care capacity to deal with the crisis.

Source: London School of Economics

Language: English

Date: 25 March 2020

What Does it Say? The site is a tool that visually represents Lebanese corporate registry data, which can be searched by company, individual, and family names.

Reading Between the Lines: The dynamic chart offers a window onto the intertwined business networks between Lebanon and Syria.

Source: Shin Mim Lam

Language: Arabic

Date: No date

MENA coronavirus update: The region faces an unprecedented crisis

What Does it Say? The novel coronavirus is rapidly spreading throughout the Middle East, where it is projected to have uniquely devastating humanitarian and economic ramifications.

Reading Between the Lines: The current pandemic has revealed the high degree of systemic fragility across the Middle East, which has resulted from ongoing wars, poverty, and economic crises.

Source: Middle East Institute

Language: English

Date: 23 March 2020

COVID-19 and Conflict: Seven Trends to Watch

What Does it Say? While COVID-19 has already had crushing humanitarian and economic ramifications, it is not yet clear whether it will help tamp down tensions for the foreseeable future or sow the seeds of further conflict.

Reading Between the Lines: The economic fallout of the coronavirus will be considerable, yet the response may foster greater global cooperation. While many needed responses are outside the remit of ‘quick-fix’ solutions, sanctions relief would be one means of making a profound life-saving impact.

Source: International Crisis Group

Language: English

Date: 24 March 2020

Lebanese Hezbollah’s Experience in Syria

What Does it Say? At the onset of the Syria conflict, Hezbollah’s presence was limited to Syria-Lebanon border regions. However, it has since been drawn into a more robust presence, notably throughout the predominantly Shia areas of southern Syria and Damascus, where economic interests have added to its influence in the region.

Reading Between the Lines: The economic opportunities afforded by the lawless nature of Syria have become a considerable driver of conflict, and continue to empower non-state actors. Drug networks, in particular, have been transformed into a key source of revenue to fund conflict activities, which have now become a means in and of themselves.

Source: European University Institute

Language: English

Date: 13 March 2020

What Does it Say? The author contends that although China has continued its nominal political support for the Government of Syria, both from the sidelines and in the UN Security Council, this has been limited by the potential for clashes with American Interests.

Reading Between the Lines: China is keen on cementing its signature foreign policy: the Belt and Road Initiative, which envisions a sweeping trade route connecting China to the Persian Gulf, the Arabian, Red Sea, and the Mediterranean basin. China is engaged in a delicate balancing act to make this happen, and there is good reason to doubt China’s willingness to wade into the political thicket in Syria to make this project happen.

Source: Chatham House

Language: English

Date: March 2020

Deir ez-Zor residents protest rule by Syrian Kurdish group

What Does it Say? Civilians in SDF-controlled areas are increasingly vocal over the lack of services and the repressive policies implemented by the SDF.

Reading Between the Lines: Rather than using oil revenues to fund basic services, the SDF has been accused of funding military ventures and further recruitment. These governance missteps may doom outlying areas of northeast Syria to a vicious cycle of localized violence and repressive policies to contain dissatisfaction.

Source: Al Monitor

Language: English

Date: 20 March 2020

Syria war: The myth of Western inaction in Idlib

What Does it Say? The author contends that despite the widespread belief that Western powers have been totally absent from northwest Syria, these governments do, in fact, bear partial responsibility for the current state of affairs, due to differing priorities, strategic errors, and a lack of interest.

Reading Between the Lines: At the onset of the Syria conflict in 2011, many Western governments quietly advocated for war to bring down the entrenched ruling class in Syria. While much of the blame does lie with the Government of Syria, Western powers are, in many ways, partially responsible for the growth and empowerment of extremist groups in Syria.

Source: Middle East Eye

Language: English

Date: 20 March 2020

The Wartime and Post-Conflict Syria project (WPCS) is funded by the European Union and implemented through a partnership between the European University Institute (Middle East Directions Programme) and the Center for Operational Analysis and Research (COAR). WPCS will provide operational and strategic analysis to policymakers and programmers concerning prospects, challenges, trends, and policy options with respect to a conflict and post-conflict Syria. WPCS also aims to stimulate new approaches and policy responses to the Syrian conflict through a regular dialogue between researchers, policymakers and donors, and implementers, as well as to build a new network of Syrian researchers that will contribute to research informing international policy and practice related to their country.