Syria Update

15 June 2020

Table Of Contents

Download PDF Version

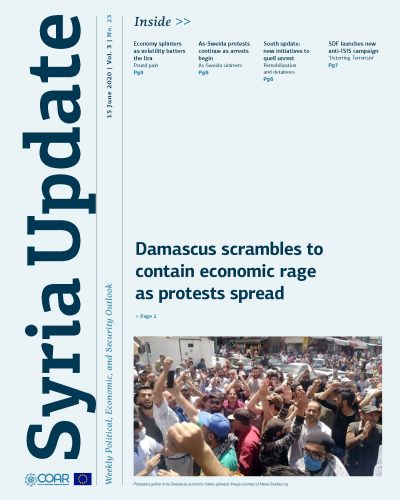

Damascus scrambles to contain economic rage as protests spread

In Depth Analysis

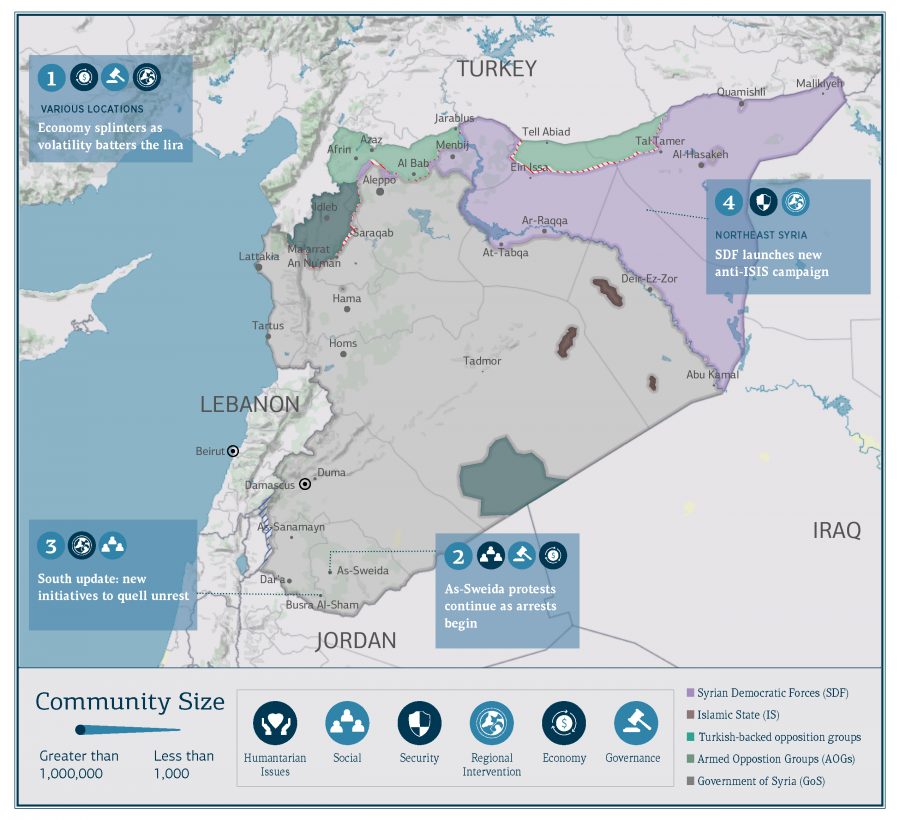

On 11 June, Syrian President Bashar Al-Assad dismissed Prime Minister Imad Khamis and announced that Hussein Arnous, Syria’s minister of water resources, will succeed Khamis as interim prime minister. While no formal explanation for the move was given, the firing is likely intended to meet the intense public pressure that has built up over the widespread economic protests now taking place across Government- and opposition-held Syria. Thus far, the most notable epicenter of demonstrations has been As-Sweida, where protesters have launched a series of demonstrations demanding the ouster of Bashar Al-Assad as well as material improvements, due to the state’s inept mishandling of the economic crisis and the Syrian pound’s rapid depreciation to record lows (see: Syria Update 8 June). Further demonstrations over dismal economic conditions have taken place elsewhere, including Dar’a, Rural Damascus, Homs, and in opposition-held Idleb.

It is crucial to note that the underlying drivers of the intense public anger are intractable and cannot be solved by cosmetic changes. Khamis had long been a target of popular dissent, but his sacking is a superficial gesture that will not alter the fact that the Government of Syria likely lacks the tools needed to repair the structural defects that hamper the national economy (see: Syria Update 26 May). As a result, the dismal conditions that are now pervasive across Syria can be expected to worsen unless outside intervention occurs, thus fueling popular dissatisfaction and further protest.

Hail Caesar?

Many Syrian activists and analysts have noted that the popular rage currently directed at Damascus resembles the opening stages of the Syrian uprising in March 2011. Certainly, similarities between the current context and 2011 do exist. Worryingly, in terms of economic destitution, conditions are now far more dire than at any time in Syria’s modern history. As a result, there is growing discourse within Western policy circles and inside Syria itself that immiseration will fuel the domestic popular resentment needed to unseat Bashar Al-Assad. At the center of these discussions lie the Caesar sanctions, which are slated to enter force this week. In effect, proponents of the Caesar sanctions argue that increased economic pressure on the Al-Assad regime can be used as a wedge to demand political or humanitarian concessions. There is also the implicit understanding that further economic and material deprivation of the Syrian population would lead to a renewed domestic protest movement against the Al-Assad regime. Variously, proponents of the sanctions argue that Russia, Iran, or various regime insiders may be willing to sacrifice Al-Assad in response to the suffering of the Syrian population.

This is a dubious proposition. Although the precise impact of the sanctions has been debated, Syrian activists, Western analysts, and policymakers have consistently and almost universally underestimated Al-Assad’s staying power. In this respect, historical perspective is instructive. As the armed opposition gained momentum in Syria, the conviction that Al-Assad would step down in the face of strident resistance became the bedrock logic underlying the international community’s approach to the Syria crisis. To a large extent, Western political and military strategy in Syria was designed to accelerate the regime’s downfall. Consequently, the humanitarian and development response was largely oriented toward preventing the worst humanitarian effects of state collapse while simultaneously building up alternate civil, administrative, and governmental entities through initiatives such as the ‘Day After’ project. However, between 2015 and 2018, the Government of Syria’s battlefield victories changed the landscape in Syria, and the international response has struggled to adapt by reconciling its political hopes and strategic objectives with the reality of the conflict in 2020.

Now, the confluence of widespread economic protests and new sanctions has brought discussion of Al-Assad’s fate to the fore once again. However, it is important to keep the protests in proper perspective. Although growing in geographic scope, the protests have been relatively small in scale. Additionally, much has changed in Syria and the region since 2011, and on a fundamental level, it is unlikely that demonstrators are now either willing or able to retrace the steps that converted the incipient popular protest movement into an effective armed opposition almost a decade ago. In this respect, three realities must be borne in mind.

- First, the Syrian opposition has changed. Despite continuing political support for the opposition on the international level, inside Syria, the opposition is now isolated, and it will likely remain cut off from material support. Pockets of localized armed insurgency do exist, particularly in southern Syria, while opposition sentiments persist throughout the country. However, on the whole, the Syrian opposition lacks the economic, political, and military tools required to mount a credible armed challenge to the Government of Syria.

- Second, the region has changed. Material and logistical support by regional actors was instrumental in the considerable territorial successes achieved by opposition forces. Jordan and Turkey served as important staging grounds for support to the Syrian opposition. Monetary contributions from the Gulf were also critical to military, political, and civil society initiatives in areas outside Government of Syria control. However, Russia’s military intervention in late 2015, marked a paradigm shift in the Syria conflict. By slowly reclaiming territory through a divide-and-conquer strategy that was enabled by Russia, the Government of Syria successfully dismantled the armed opposition and has relegated its most effective actors to a Turkish-controlled enclave in northern Syria. With the exception of Turkey, regional actors are now unlikely to risk antagonizing the Government of Syria by providing support to any opposition. Jordan has re-opened its border with Syria, and discussions have taken place over regularizing important cross-border commercial trade. Likewise, multiple Gulf states have their signalled willingness to normalize relations with Damascus. Although the impending Caesar sanctions will derail regional hopes of a reconstruction windfall, Gulf actors are unlikely to risk alienating Damascus in support of a nascent anti-Government movement.

- Third, the Syrian state is not the regime, and the collapse of the Syrian state would not necessarily trigger the collapse of the regime. The ‘Syrian regime’ is difficult to precisely define, but it can be understood as the innermost circle of the Syrian political, security, and business elite which has at its center Syrian President Bashar Al-Assad. Although this structure is deeply interwoven within the Syrian state apparatus, the regime and the state are not synonymous. The regime has proven durable, and the collapse of the state due to economic contraction, currency depreciation, political isolation, and sanctions would not necessarily bring down the regime with it. It is critically important to note that it may be possible for the regime to survive the collapse of the Syrian state itself.

These realities suggest that the Syrian population will have extremely limited means of challenging the Government of Syria. In turn, this calls into question the underlying logic of efforts to isolate or coerce the Syrian regime. As a result, theSyrian population now faces a menacing array of challenges that will likely remain irrespective of the fate of Bashar Al-Assad. The Syrian state is marked by deep economic instability. Returns are effectively frozen. Food insecurity is rising, and famine has been noted as a distinct possibility. Should these conditions persist, they are likely to fuel a cycle of violence, displacement, and migration that will have knock-on effects not only in Government-held Syria, but also in neighboring territories and internationally.

Whole of Syria Review

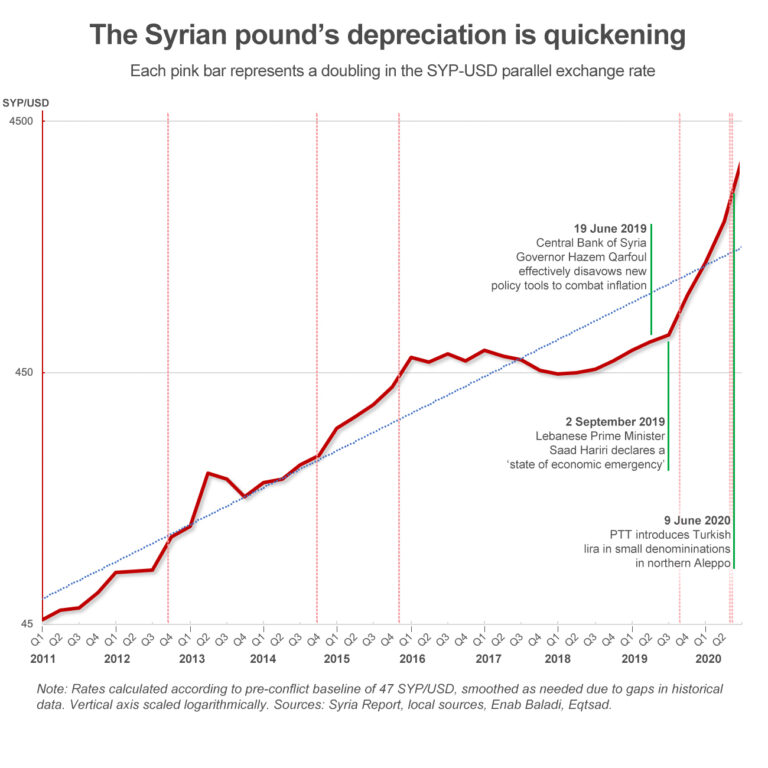

1. Economy splinters as volatility batters the lira

Various Locations: As a result of the most radical economic volatility in Syria’s modern history, the national economy has begun to splinter into regional enclaves. As a result of the Sryian pound’s depreciation, administrative officials in Turkish-controlled areas of northwest Syria have begun to introduce Turkish lira in small denominations in a bid to restore stability by ditching the Syrian pound altogether. On 9 June, local media reported that the local council in Mare’, in northern Aleppo, called for the use of Turkish lira for small-to-medium commercial transactions, while U.S. dollars would remain in use as a peg to fix prices for administrative-level actions such as wages and crop prices.

Currency crunch

Syria is not yet in technical hyperinflation, but public confidence in the Syrian pound is in tatters. The pound has charted a steady decline throughout the conflict, but the speed and scale of the latest slump in parallel market values have shredded confidence in the currency — as well as consumer purchasing power. Reports are now rampant that market prices are updated on a rolling basis, and it has been widely reported that many traders have simply refused to conduct business due to volatility. These effects have been particularly impactful because the majority of Syrians are public-sector employees whose fixed incomes have remained virtually flat throughout the conflict. For instance, a public-sector PhD-holder earns 57,495 SYP per month (approx. $23), and inflation has now crossed a threshold beyond which even top-tier salary earners have little real purchasing power.

The phased introduction of small-denomination Turkish currency into northern Aleppo will likely bring welcome relief from volatility. This is especially true if the currency does achieve widespread circulation for daily transactions, as seemingly intended. However, doing so would signal a further erosion of the Government of Syria’s claim to legitimacy in the area, and it would be a milestone in cementing Turkish influence in an area that is already tightly interwoven with corresponding Turkish provinces. The impact of Syria’s economic volatility has been immense, and throughout Syria, the obliteration of livelihoods will likely be a further driver of conflict, military recruitment, international drug smuggling, and — reportedly — organ trafficking (see: Syria Update 8 June).

2. As-Sweida protests continue as arrests begin

Sweida, As-Sweida governorate: On 10 June, the Government of Syria reportedly compelled state employees and college students in As-Sweida to attend a public rally in support of President Bashar Al-Assad, according to a leaked recording in which a high-ranking Ba’ath party official threatens severe punishment against individuals who do not participate. Of note, protests in As-Sweida began earlier this month against the backdrop of the Syrian pound’s rapid depreciation, and have since expanded to other locations in the country. Demonstrators have remained in the streets in As-Sweida to demand the release of Raed Al-Khateeb, a prominent local journalist who was arrested in a Political Security branch raid in Burj Enji in Sweida. Reportedly, Al-Khateeb’s release is being negotiated by local notables.

Protests escalate with a familiar call: Bashar must go

Together, the escalating tone of public demonstrations in As-Sweida and the state’s overbearing response signal a deepening political intensity to unrest in the region. In the past, such protests have sought attention for a broad but often strategically apolitical set of issues, primarily related to living conditions. Now, protesters have explicitly called for the ouster of Al-Assad, as well as an improvement to security conditions, an end to endemic corruption, and the withdrawal of Iranian militias and Russian troops from Syria. Similar protests have kicked off elsewhere in Syria, but the Government has not met these challenges sitting down. The arrest of Al-Khateeb is a reminder that the Government is willing to take decisive action to resist the political challenges made against it. The forced attendance at a pro-Government counter-demonstration is not necessarily a new phenomenon, but it does show the lengths to which Government forces will go to manufacture consent as public criticisms mount. Though demonstrations in As-Sweida have remained relatively small, they can be expected to increase in size and gain momentum, given the Government’s limited capacity to address growing hardships or stabilize the Syrian pound in the long term. The events are also a signal of how the Government may respond elsewhere in Syria as protests continue.

3. South update: new initiatives to quell unrest

Busra Al-Sham, Dar’a governorate: On 7 June, local media sources reported the 5th Corps conducted a large meeting in Busra Al-Sham with communal representatives from eastern and western Dar’a governorate to discuss the recruitment of former opposition fighters and others for the 5th Corps. Reportedly, recruits are slated to undergo a 15-day training program before joining armed formations tasked with enforcing security in their communities. Should the scheme be implemented as planned, the 5th Corps 8th Brigade will establish a field office for local recruitment. Relatedly, on 7 June, Russian forces established a center at the White Rose Hotel in Dar’a to provide information about detainees held in Government of Syria prisons. Those seeking information must provide a copy of the missing person’s ID, a picture of the prisoner, and information about the place and date of detention.

Twin initiatives to wind down tensions

Following weeks of pitched unrest in Dar’a and a massive show of force by the Government of Syria, twin enterprises to de-escalate tensions in the community have emerged in the form of military remobilization and a nascent initiative to locate detainees. Both activities address sources of significant discontent that remain drivers of instability. Yet questions remain. Russia’s position vis-a-vis the 5th Corps recruitment process is not clear, particularly given its backing for the 4th Division, which is also promoting recruitment in the area under its own aegis. Local sources indicate that the 5th Corps’ bid may represent an attempt by former Quwat Shabab Al-Sunna commander Ahmed Odeh to maintain leverage in response to reports that Russia is considering establishing a consolidated formation of former opposition fighters. The rumored formation will reportedly be called the First Corps and could compete for influence, but its status is speculative. The detainee initiative is equally difficult to predict. One member of the Dar’a central committee was quoted saying that the committee has submitted lists containing the names of prisoners to Russian representatives and the Government of Syria on multiple occasions for more than two years. To date, details on the initiative remain scarce, and there is little clarity concerning the mechanism to release detainees.

4. SDF launches new anti-ISIS campaign

Northeast Syria: On 4 June, Syrian Democratic Forces announced the opening phase of a sweeping counter-ISIS campaign in coordination with Iraqi government forces, the Kurdish Peshmerga, and the U.S.-led international coalition. The area targeted by the SDF stretches across southern rural Al-Hasakeh governorate to Baghouz in eastern Deir-ez-Zor governorate and across the Syria-Iraq border. The first phase of the campaign reportedly ended on 10 June, with the SDF conducting raids on 65 locations and arresting 110 individuals suspected of links to ISIS. Additionally, the SDF stated that it had seized a large number of weapons, including pistols, silencers, and homemade explosives in the campaign. Meanwhile, on 10 June, local security forces at Al-Hol camp reportedly began a new phase of identifying foreign female detainees at the camp with suspected links to ISIS.

‘Deterring Terrorism’ campaign

While ISIS has been eliminated as a territorial entity, its ideology remains difficult to uproot. In this respect, several key takeaways are important to note. First, local sources indicate that the ‘Deterring Terrorism’ campaign comes as a direct result of the gradual increase in ISIS activity in the area. Second, local sources also indicate that the campaign reportedly targeted not only ISIS-affiliated suspects but is also believed to have singled out political antagonists of the SDF, including individuals affiliated with the Government of Syria or formal opposition factions. While difficult to verify, the existence of such beliefs is likely to deepen the sense of alienation such actors already feel toward the SDF and the Self Administration more generally. Third, although anti-ISIS activities are a cornerstone of the SDF’s overall security portfolio, it is novel for such a campaign to focus on southern Al-Hasakeh governorate. It is axiomatic that such campaigns have been effective vehicles for degrading ISIS capacity holistically, yet they are unlikely to be a coup de grace. Challenges to the legitimacy of the SDF and Self Administration will continue to provide ideological fodder to the group’s activities. Likewise, ineffective coordination among security actors operating in Iraq and Syria’s rural borderlands will also be a boon to the group. To this end, U.S. special envoy to counter ISIS, James Jeffrey, has stated that coordination challenges between the Peshmerga and Iraqi security — in particular, the Popular Mobilization Forces — have led to gaps in which ISIS activity has continued unchecked. This suggests that without a broader cooperation framework, reducing regional ISIS activities to zero will be extremely challenging, if not impossible.

Key Readings

The Open Source Annex highlights key media reports, research, and primary documents that are not examined in the Syria Update. For a continuously updated collection of such records, searchable by geography, theme, and conflict actor, and curated to meet the needs of decision-makers, please see COAR’s comprehensive online search platform, Alexandrina, at the link below.

Note: These records are solely the responsibility of their creators. COAR does not necessarily endorse — or confirm — the viewpoints expressed by these sources.

Will More Syria Sanctions Hurt The Very Civilians They Aim To Protect?

What Does it Say? The authors give a thoroughgoing account of the impact of the U.S. Caesar sanctions, which are set to go into effect this week with the aim of pressuring the Government of Syria into making significant political concessions.

Reading Between the Lines: The sanctions are hotly debated, but there is broad agreement that they will likely increase the hardship facing the very civilians they are meant to protect.

Source: War on the Rocks

Language: English

Date: 10 June 2020

What Does it Say? In the past week, rare protests against President Bashar Al-Assad in the Druze-majority As-Sweida have continued and spread across Syria.

Reading Between the Lines: Calls to capitalize on Syria’s economic unrest as a wedge to unseat Bashar Al-Assad are likely to mount as the turmoil grows.

Source: The Syrian Observer

Language: English

Date: 14 January 2020

Syria Timeline: Since the Uprising Against Assad

What Does it Say? An interactive timeline detailing the major events of the Syrian conflict from 2011 to present.

Reading Between the Lines: With useful annotations, the timeline is among the most comprehensive and detailed resources charting the escalation, expansion, and evolution of the conflict.

Source: United States Institute of Peace

Language: English

Date: 04 June 2020

This global pandemic could transform humanitarianism forever. Here’s how

What Does it Say? The COVID-19 pandemic has raised many questions about how it will change humanitarianism.

Reading Between the Lines: There is no doubt that humanitarianism in all its aspects will undergo significant reforms as a result of the pandemic’s aftermath.

Source: Asharq Al-Awsat

Language: Arabic

Date: 9 June 2020

Turkey decides to purchase cereal crops in the areas of Tal Abyad and Ras Al-Ain

What Does it Say? Turkey has vowed to purchase the entire grain crop of Tel Abiad and Ras Al-Ain in northern Syria.

Reading Between the Lines: Turkey’s decision to purchase grains grown in the Peace Spring area is a further reminder of its ambition to exercise greater administrative and economic control over northern Syria.

Source: Enab Baladi

Language: Arabic

Date: 10 June 2020

The Future of Northeastern Syria: In Conversation with SDF Commander-in-Chief Mazloum Abdi

What Does it Say? The article offers a wide-ranging look at the view of the SDF commander.

Reading Between the Lines: Among other topics, the piece covers the SDF’s awkward position vis-a-vis the political opposition and Damascus, which refuses to budge on the issue of formal recognition.

Source: The Washington Institute

Language: English

Date: 10 January 2020

What Does it Say? The podcast assesses the rapidly deteriorating economy of Syria,where 85 percent of the population already lives in poverty.

Reading Between the Lines: The Caesar sanctions which are set to take into effect this week will likely worsen these conditions, which are likely to become a further driver of instability.

Source: Middle East Institute

Language: English

Date: June 2020

The Wartime and Post-Conflict Syria project (WPCS) is funded by the European Union and implemented through a partnership between the European University Institute (Middle East Directions Programme) and the Center for Operational Analysis and Research (COAR). WPCS will provide operational and strategic analysis to policymakers and programmers concerning prospects, challenges, trends, and policy options with respect to a conflict and post-conflict Syria. WPCS also aims to stimulate new approaches and policy responses to the Syrian conflict through a regular dialogue between researchers, policymakers and donors, and implementers, as well as to build a new network of Syrian researchers that will contribute to research informing international policy and practice related to their country.