Syria Update

5 October 2020

Draft budget: The Syrian state continues to shrink

In Depth Analysis

On 28 September, the High Council of Economic and Social Planning approved the draft 2021 general budget submitted by Prime Minister Hussain Arnous. At around 8.5 trillion SYP, it represents a 113 percent nominal increase from 2020’s budget (see: Syria Update 27 November – 3 December 2019). However, in dollar terms, the budget has withered to $3.86 billion, down more than 10 percent from last year. But that tells only part of the story. Significant files are excluded from the budget, which is better seen as a reflection of the state’s ambitions than its abilities. In effect, the budget is a public relations tool, and it shows how the Syria state is attempting to stretch its diminishing resources to cover growing needs.

Paper tiger: How big is the budget, really?

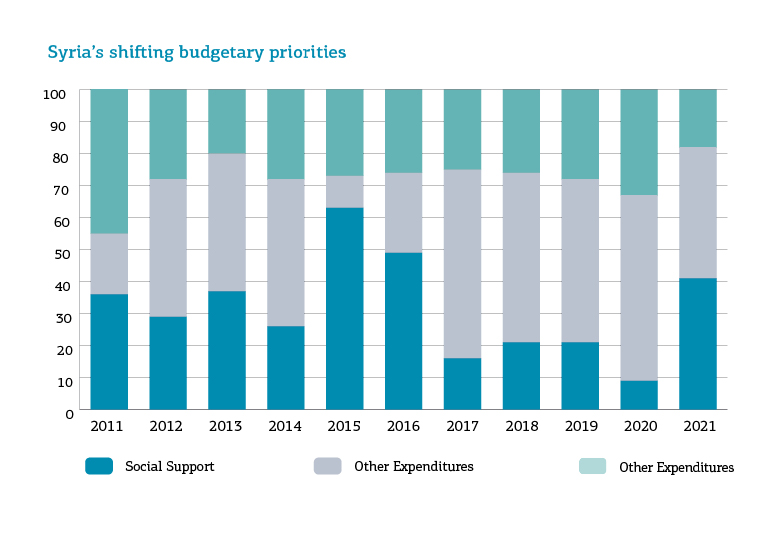

At the Central Bank of Syria’s generous pegged conversion rate, the budget amounts to $6.8 billion, yet that fiction has little bearing on reality. Damascus can mask its own shrinking fiscal capacity through conversionary legerdemain, but the nominal re-allocation of diminishing state resources is revealing. As the productive economy, national industry, and service sector crumble, the state is concentrating a greater share of its limited resources on basic social support. For instance, the budget sets aside a mere 100 billion SYP ($45 million) for state-owned enterprises and allocates only 40 billion SYP ($18 million) to targeted sectors, including agriculture, tourism, and industry. Three crucial files are absent from the draft budget altogether. Among them are the electricity sector and the state’s reconstruction fund, which were promised 711 billion SYP and 50 billion SYP in 2020. The third and most important is military spending, which disappeared from state budgets years ago.

In parallel, the state has pledged to plow more than 41 percent of its total budget into basic support to the immiserated populace. At 3.5 trillion SYP ($1.59 billion), social support constitutes the largest line item in the budget, and it is by far the biggest mover from 2020, when it soaked up only 360 billion pounds. Social support includes 2.7 trillion SYP to subsidize oil products, 700 billion SYP to subsidize wheat and flour, and 50 billion SYP for the Agricultural Support Fund. This significant expansion in the social support allocation aligns with the pledges of the government headed by recently appointed Prime Minister Hussein Arnous, which has emphasized the state’s commitment to improve the livelihoods of Syrians, prioritizing basic goods subsidies, and curbing unemployment — heady tasks that are seen as the government’s chief mandate (see: Syria Update 15 June).

The disappearing Syrian state

The budget announcement was accompanied by governmental pledges to prioritize social support and small and medium industrial and agricultural projects. On paper, the pledges mark a significant jump from 2020 (moving from $500 million to $1.59 billion). However, the proposal has been met with justified skepticism. State revenues have plummeted at least 80 percent since 2011, due to diminished tax collection, the partitioning of the oil and gas sector, and a significant drop in exports of all kinds amid extensive destruction. These conditions are locked in by Syria’s isolation, the depth of Lebanon’s financial crisis, and the toxic aura created by sanctions, which also complicate the aid environment.

The Syrian government is likely to resort to three approaches to fund its spending plans. Firstly, printing more money. This measure may cover nominal cash gaps, but it will also fuel inflation, stunt livelihoods, and further erode the state’s capacity to fund vital imports. Secondly, Damascus may turn to its allies Russia and Iran. In-kind support such as the Iranian credit line is one notable example. However, Russia has been slow to deliver on its promise of wheat aid, and concessions in key sectors such as energy, telecommunications, and natural resources are the likely price to pay for this support. Thirdly, it is also possible that local business elites will be compelled to support the state directly. Direct dollar deposits with the Central Bank of Syria may bring some stability, reinforcing the pact that binds war economy elites to the state apparatus (see: Syria Update 25 September – 1 October 2019). Over the past year, Damascus has targeted several tycoons and frozen or confiscated their assets, including Rami Makhlouf, Sa’eb Nahhas, and Hani Azouz.

Smoke and mirrors?

Despite the picture that emerges from published figures, drawing firm conclusions from the Syrian state budget is a fraught exercise. The Government of Syria is constitutionally opaque. The absence of military spending means that any published budget should be seen more as a public relations exercise than a roadmap for austerity governance. Moreover, since 2012 Damascus has not published budget reconciliation reports at the end of the fiscal year, making it impossible to calculate surpluses, or more likely, deficits. Additionally, the state’s budgetary capacity is bracketed by the reality that the value of the Syrian pound will likely retreat throughout the fiscal year. In effect, the budget will begin to shrivel from the moment it is published, and the state’s capacity to course-correct has never been more limited.

Should the government fail to make good on its pledges, social support will likely face the ax, just as funding to vital enterprises and industries has. In the latter cases, the central state’s withdrawal from a once tightly managed national economy has forced the populace into a greater reliance on the meager assistance that is among the sole pillars in the edifice of a crumbling state. Austerity may force further changes to the subsidy schemes for basic goods such as fuel and bread, which are already in crisis. The expansion in the social support plan with no credit to cover it is a risk that may backfire and leave Syrians to confront this misery on their own. There is good reason to doubt the Government of Syria can deliver on its promises. For international aid actors, this should be a clear signal of the need to plug the resulting gaps, although doing so will require coordinated action, clear communications, and a willingness to actually deploy the leverage that has been gained as Damascus has been laid low.

Whole of Syria Review

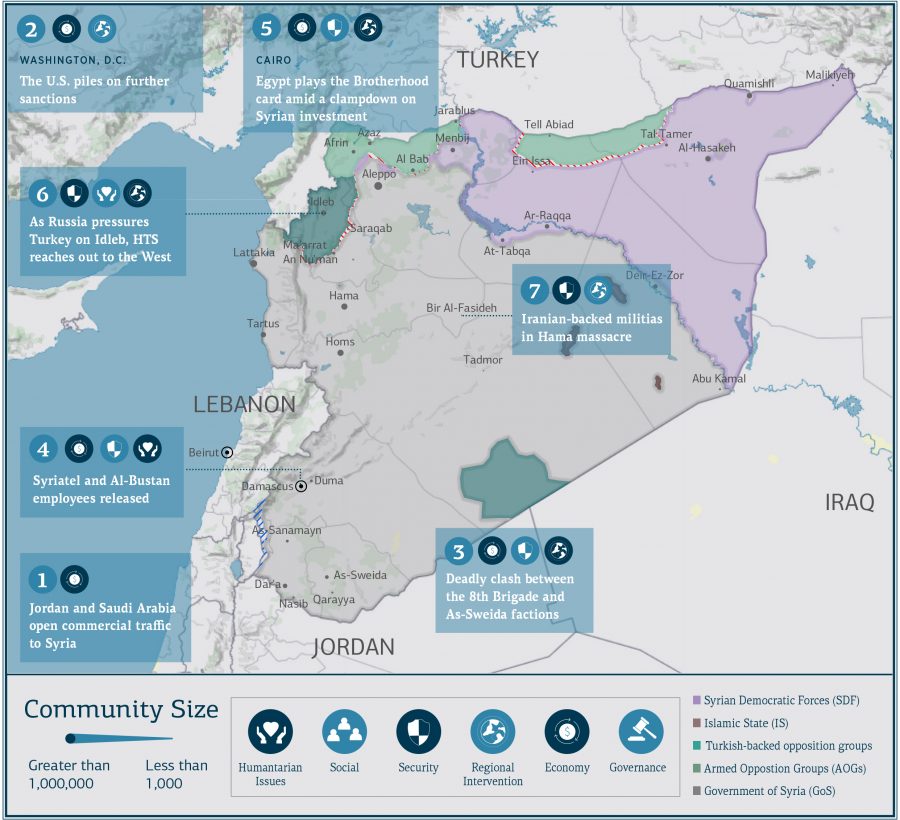

1. Jordan and Saudi Arabia open commercial traffic to Syria

Nasib border crossing: Jordan has reopened its commercial crossing with Syria at Nasib following its closure due to the COVID-19 pandemic, media sources reported on 28 September. Jordanian officials stated that the crossings were closed due to the risk of infection to Jordanian border officials. Relatedly, on 29 September, Syrian media reported that Saudi Arabia will allow Syrian trucks to transit through Saudi territory en route to other Gulf states after years of closing that throughway. Since the kingdom reopened its borders to Syrian commercial traffic, trucks have reportedly transited through Jordan on a daily basis.

A lifeline on life support

Syria’s commercial access to Jordanian markets is a lifeline, but the Gulf is a bigger prize yet. Particularly in the south, Syria’s farmers are highly reliant upon the ability to export agricultural produce to high-value markets in Jordan, although trade to the Gulf is potentially more lucrative and an augur of greater commercial cooperation to come. It is also notable because Jordan and Syria have repeatedly stumbled during commercial integration talks due to trade barriers, protectionism, and anti-competitive practices (see: Syria Update 13 January), in addition to COVID-19. Curiously, while local sources have confirmed that Jordanian borders are officially open for commercial traffic, only trucks transiting through Jordan to the Arab Gulf and Iraq have been allowed to pass through. As of writing, it is expected that trucks destined for the Jordanian market will be permitted passage in early October.

The Nasib crossing is a lynchpin of regional trade (see: Syria Update 18-24 October 2018). In 2020, Syria imported $940 million in goods through Nasib, and Syrian producers exported goods valued at $700 million. The peripheral consequences of the crossing’s closure in 2015 have been severe for other regional actors, too, including Turkey and Lebanon. While far-flung regional trade through Nasib will be slow to rebound, Syria’s agriculturalists are clamoring for an export market underpinned by stable foreign currency. Nasib’s opening will bring them much needed relief — if it stays open.

2. The U.S. piles on further sanctions

Washington, D.C.: On 30 September, the U.S. Treasury published new sanctions targeting multiple Syrian government institutions and actors, as well as a prominent Aleppo businessman. Among those sanctioned are:

- Hazem Qarfoul. Qarfoul is the governor of the Central Bank of Syria (CBS). The Treasury sanctioned Qarfoul for his role in ensuring the continued fiscal solvency of the Syrian state, including an attempt to pressure elite businessmen to deposit hard currency with the CBS (see: Syria Update 25 September – 1 October 2019).

- Khoder Ali Taher. Taher is an Alawite war profiteer who reportedly manages some of the economic files held by the 4th Division, the elite military unit commanded by Maher Al-Assad, the brother of president Bashar Al-Assad. Taher dominated crossline smuggling between opposition and Government areas, and he is a highly divisive figure within nominally pro-government circles. Taher has an especially acrimonious relationship with Aleppo’s business community, which have publicly accused him of racketeering. Of the 13 entities sanctioned under the latest U.S. order, 11 are linked to Taher.

- Syrian Ministry of Tourism. Also sanctioned is a private tour company affiliated with the ministry.

- Major General Milad Jedid. Jedid is an Alawite commander of the 5th Corps. He was reportedly targeted over the breakdown of ceasefire agreements.

- Hussam Louka. Louka is currently head of the Security Committee in Dar’a, although he continues to hold multiple positions within the Syrian security apparatus. He is most notable for suspected complicity in the bombing of Wa’er neighborhood in Homs city.

Starving the beast — or the populace?

The sanctions designations concentrate on enablers (Qarfoul), middlemen (Taher), and revenue sources (tourism ministry) of Damascus. Collectively, they evince a continuation of Washington’s deliberate efforts to erode the financial basis of the Syrian regime. As with past sanctions designations, the latest additions are designed to neutralize the Al-Assad regime’s financing appendages in hopes of starving the inner circle itself. For instance, Qarfoul’s role at CBS primarily revolves around his efforts to impose a semblance of fiscal stability amidst an unavoidable crash landing. Taher’s extensive business interests are believed to be a source of direct financing to the state itself. These interests include telecommunications, construction, and a private security firm, and they have been safeguarded by the uppermost echelons of the Syrian regime, despite the virulent protests of prominent Aleppo business elites who are also supporters of Damascus.

However, the designation of Jedid may prove to be the most consequential of the sanctions. There is ambiguity concerning his being listed. Jedid was a Republican Guard commander until joining the 5th Corps, a military formation supported by Russia. It has been speculated that the measure is a direct challenge to Russia and may signal a new American pressure tactic by outlawing the 5th Corps. Certainly, like Louka’s designation, the targeting of Jedid suggests that Washington has not given up on using maximum financial pressure to re-litigate the armed battles of long-past stages of the Syria conflict.

Looking ahead, U.S. sanctions in Syria are designed to punish and deter. Their capacity to meaningfully punish the Syrian regime and its enablers is dubious, given the regime’s tight grip over the illicit war economies that are turbocharged by the freefall of the licit domestic economy. Deterrence is an easier target to hit. Sanctions that graze Russian interests in Syria are a signal to Moscow. However, they also risk making outlaws of the former opposition fighters who have remobilized with the 5th Corps primarily because it offers stable livelihoods and protection against the Syrian government’s abuses (see: The Syrian economy at war: Armed group mobilization as livelihood and protection strategy).

3. Deadly clash between the 8th Brigade and As-Sweida factions

Qarayya, As-Sweida governorate: On 30 September, local and media sources reported that clashes took place in Al-Qaraya in southwestern As-Sweida between the Druze Men of Dignity (“Rijal Al-Karamah”) and the 8th Brigade of the Russian-backed 5th Corps. Local sources indicated that 13 people were killed and more than 50 were injured, amid heavy artillery use. Clashes ensued when the Druze factions launched an attack on 5th Corps positions in Qarayya, citing Russia’s failure to force the 5th Corps to withdraw from the territory, a grievance that has festered among communities in the western As-Sweida countryside. After intense fighting, the 8th Brigade forces succeeded in repelling the assault. Local sources indicated that Druze religious leaders held Russia responsible for the clashes and have called for a meeting with the Russian Foreign Ministry to find a solution.

Eastward ho

The 8th Brigade’s eastward expansion into the predominantly Druze territory in the western As-Sweida countryside has fostered rising antipathy between As-Sweida and Russia and its local proxy force, the 5th Corps. Alongside livelihood needs, the 8th Brigade’s encroachment was among the drivers of Iran-linked mobilization with the National Defense Forces by Sweidawis, a notable departure from the community’s long-standing tendency toward restraint and strategic distance from outside conflict actors (see: The Syrian economy at war: Armed group mobilization as livelihood and protection strategy). Russia may have refused to meet As-Sweida’s demands as punishment over the community’s independent streak, its recent coziness toward Iran and Hezbollah, and the anti-government protests that culminated in the ouster of Prime Minister Imad Khamis in June. Russia’s direct command and control over the 5th Corps is also far from absolute, as seen in anti-government protests by the 8th Brigade this summer. Altogether, the events highlight the increasingly blurry lines that separate various factions and political-military movements in southern Syria. To date, Russia’s capacity to mediate in As-Sweida has fallen short of its ambitions. The event suggests that this is likely to remain the case for the foreseeable future, and more clashes can be expected until the territorial dispute is resolved.

4. Syriatel and Al-Bustan employees released

Damascus: On 25 September, media sources reported that the Government of Syria had released dozens of Syrians working in companies and entities affiliated to business titan Rami Makhlouf. Following five months of detention, 41 Syriatel employees, 57 Al-Bustan Foundation staff, and 58 army and security officers were released, while up to 12 remained imprisoned. Of note, this mass release was not addressed in the latest of Makhlouf’s posts to his personal Facebook page, which came after months of idleness. Rather than speak to the well-being of the newly released individuals, Makhlouf renewed his denunciation of the state figures who seized his companies, describing them as “mercenaries and traitors,” while warning that such “injustice will not go unnoticed.” However, Makhlouf did call attention to the targeting of his humanitarian initiatives, warning of the drastic impact such actions have on the “loyal communities” that have defended the government over many years during the conflict.

Collateral damage of the ruling elite’s dispute

To date, none of the detainees has been formally prosecuted, and the Government of Syria has not issued any official statement explaining the mass arrests — or the sudden release of dozens of the detainees. If anything, the arrests show the danger implicit in being caught in the crossfire of a dispute between Syria’s ruling elites, and they illustrate the degree to which the state and security apparatuses are employed to resolve personal disputes among Syria’s most privileged. Makhlouf previously accused the Government of Syria of arresting his employees to intimidate him in an effort to drive him to abandon his business interests and pay back taxes allegedly owed by Syriatel. Now, the release of the employees followed a series of decisive actions taken by the Government of Syria to jettison Makhlouf and effectively wrest control of both Syriatel and Al-Bustan from the tycoon. The state forced a restructuring of Syriatel and expelled numerous officials, including former executive manager Majeda Saqer, who was replaced by Mureed Attasi, rebranded Al-Bustan Foundation as Al-Areen Charity Institute, and raised up Makhlouf’s brother Ehab, who was granted a number of his brother’s terminated contracts, including a deal to take over Syria’s lucrative duty-free operations. This might be one of the last episodes of the most prominent rift within the Syrian ruling clan for decades. However, its economic and social consequences are still far from a decisive conclusion.

5. Egypt plays the Brotherhood card amid a clampdown on Syrian investment

Cairo, Egypt: Amid rising tensions and the outbreak of some anti-government protests, the Egyptian government is reportedly seeking to tighten its control on Syrian investments in the country. An August memorandum by the Minister of Local Development, General Mahmoud Sha’arawi, circulated to other government ministries, accused the Syrian community of “inexplicable” financial gains during the past eight years and pointed the finger at Qatar and the outlawed Muslim Brotherhood for secretly financing the operations. The memorandum requires all new commercial licensees to obtain prior security clearances. Subsequent reports have also added that Egyptian banks have been instructed to monitor Syrian bank accounts for sudden increases in value.

Considering that Syrian businesses must already receive security clearances from the Interior Ministry to procure licenses, whether from the Egyptian Investment Authority or from the Ministry of Manpower, it has been suggested that the main impact of the decision is in its underlying political messaging.

Good for the economy, even better scapegoats for the state

The restrictions on Syrian businesses are a win-win for Cairo. In a hugely unpopular move, the Egyptian government recently announced its plans to regularize the status of millions of informal housing units. The plan imposes a compulsory “regularization” fine on millions of already-struggling Egyptians under the threat of demolition, which has followed years of unpopular austerity policies and tax raises. With the outbreak of local protests in September, Syrians are emerging as convenient scapegoats for the country’s economic difficulties. Most small Syrian businesses are already unable to gain commercial licenses, and the decision may, therefore, be seen as an attempt to pressure unlicensed business owners to regularize their commercial activities. Others believe that the new proposals will primarily seek to target large Syrian enterprises, as part of the cash-strapped state’s efforts to extract (or in this case, extort) as much capital as possible.

As part of Egypt’s attempt to lead a regional confrontation against Turkey, the new decision may likewise signal a crackdown on members of the Syrian diaspora, and it implicitly links them to the Turkish-backed opposition. Targeting the Syrian diaspora would also ameliorate the frustrations of aggrieved Egyptian business people who have seen their market share dwindle due to Syrian economic successes. Thirty thousand Syrian businesspeople and investors are estimated to be present in the country, and Syrians have invested an estimated $800 million into the Egyptian economy (although precise figures are elusive, considering that many businesses are informal or registered under an Egyptian citizen’s name). However, the Syrian Businessmen’s Association, which represents Syrian commercial interests in the country, puts the number at $23 billion. In effect, the crackdown on business in Egypt is a reminder that although regional affairs likely do influence decision-making vis-a-vis the Syrian diaspora, all politics remains local.

6. As Russia pressures Turkey on Idleb, HTS reaches out to the West

Idleb governorate: Local speculation has erupted over the future of the Idleb ceasefire amid Russian media reports claiming that Russia and Turkey are negotiating a territorial exchange between the Turkish-backed Syrian opposition and the Russian-backed Syrian government. Russian media has reported that Turkey is negotiating for a withdrawal of Syrian government forces from the Syrian Democratic Forces-held areas of Tel Rifaat and Menbij, which have long been a target of both Turkey and the armed opposition, to pave the way for a Turkish-rebel offensive. The reports come against a backdrop of Russian pressure for the withdrawal of Turkish observation points stranded in recaptured government-held territory in southern Idleb and the withdrawal of heavy weapons from remaining rebel-held areas in the south of the province. Russian airstrikes in Idleb have also escalated in recent weeks.

All eyes on Idleb, no sign of a land swap — yet

Russian-Turkish territorial exchanges do have a long precedent in Syria, but there is little hard evidence that the powers are now on the verge of such a deal. The land swaps have generally followed a pattern of Russian acquiescence to Turkish military operations in exchange for Turkey’s facilitation of strategic territorial gains for the Syrian government (see: ‘Land Swaps’: Russian-Turkish Territorial Exchanges in Northern Syria). Seemingly more likely than a land swap is the possibility of a breakdown in the Idleb ceasefire. Turkish sources have not confirmed the Russian media reports, and Ankara is understood to be reluctant to agree to any further exchanges. Altogether, the current accommodation is more fragile than at any point since it was cemented in March. Turkish Foreign Minister Mevlut Cavusoglu has stated that talks with Russia over Idleb’s fate have been “unproductive” and Cavusoglu warned the ceasefire is on the brink of collapse. In parallel, Turkey has reportedly refused to withdraw its stranded observation points, and has since dispatched large military convoys to Idleb, while mobilizing the Syrian National Army (SNA) in preparation for any flare-up in armed activities.

New tests to an old balancing act

If or when Idleb sees the return of large-scale military operations, one of the critical aspects of the region’s stability will be the perennial issue of Hay’at Tahrir Al-Sham (HTS). The group has adopted a hardline stance opposing any land swap, fearing that territorial losses in the south may facilitate attempts in the future (including by Turkey and the SNA) to eliminate the group if Turkey’s calculations change.

Nonetheless, in recent months, HTS leadership has reached out to Western countries in a bid for normalization. The most notable effort to whitewash the group’s image was a rare interview of HTS leader Abu Muhammad Al-Jolani with the International Crisis Group earlier this year. Al-Jolani struck a strong conciliatory line and admitted mistakes by the group. He also ruled out the possibility that HTS would be instrumentalized against the West and touted its efforts against ISIS cells and resistance to Huras Al-Din, including by forcing the latter to pledge not to launch an “external Jihad” from Syria. Al-Jolani further pledged that the operations of Western NGOs would not be interfered with and that the group was ready to reconcile with NGOs that faced problems with HTS in the past. HTS officials have also continued to call for Western humanitarian support in coordination with the Salvation Government, and even against the Al-Assad regime.

All told, HTS appears to be making efforts to prove its value to Turkey and the West. Following a policy of containment vis-a-vis hardline groups in Idleb, notably the Al-Qaeda-linked Huras al-Din. This high wire act entails particular risks for the group. The most obvious is the risk of failure to rebrand and shed its radical label. Although Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov has adopted a softer tone regarding HTS, this hasn’t been mirrored in Western capitals (see: Syria Update 28 September). There are also risks to the group locally. Outreach to the West has provoked heavy condemnations from inner circles (although conspicuously, Al-Qaeda’s central leadership has been largely silent). HTS has been accused of handing territory back to the Al-Assad regime, protecting Russian patrols, tyrannical governance, arbitrary arrest of muhajerin (“immigrants” — including a French fighter designated by the U.S. as a “global terrorist,” a British aid worker and a U.S. journalist), and even of possibly coordinating with U.S. airstrikes targeting Huras al-Din fighters.

Already, local discontent with HTS and its affiliated Salvation Government is high, with communities under the group’s rule feeling squeezed by heavy taxation. These have only added to the stresses brought about by continued complaints of misgovernance and potential increased U.S. strikes on Idleb under a Biden administration. In the meantime, HTS is likely to continue to present itself to the international community as a de facto governance reality, along the lines of Hamas and Hezbollah. The group’s long-term aim may be to frame itself as the sole actor capable of stabilizing the humanitarian crisis in the northwest by providing strong governance and services and preventing further migration flows. As with the other groups, HTS is attempting to assure the West that while its domestic messaging may be unfriendly to the U.S., it is taking active steps to prove that it is not a threat.

7. Iranian-backed militias in Hama massacre

Bir Al-Fasideh, Hama governorate: Iranian-backed militias reportedly killed 15 civilians, mostly bedouin shepherds, in a massacre in the rural Hama village of Bir Al-Fasideh, according to media reports. In recent months, dozens of civilians have reportedly been killed in the countrysides of Hama, Homs, Aleppo, Deir-ez-Zor, and Ar-Raqqa. The attacks reportedly increased in frequency following the killing of Iranian General Qassem Soleimani in a U.S. airstrike in January. Some of the killings have been knife attacks, a known militia practice. The Syrian government has typically blamed ISIS cells for such attacks, despite its claims the areas have been “liberated” from the group.

Out of sight, out of mind

Over the past few months, several attacks on rural shepherds have taken place in the eastern countryside of Hama. Some of the attacks have concerned competition over resources, demonstrated by livestock theft, this has not always been the case. In July, militiamen reportedly slaughtered hundreds of cattle without stealing anything, in addition to burning homes and vehicles. On at least one occasion, such attacks prompted locals to defend themselves and fire back.

Iranian-backed militias are not monoliths, composed of fighters from Syria, Iraq, Iran, Lebanon, and as far afield as Afghanistan and Pakistan. While Lebanese fighters (Hezbollah) have — generally — demonstrated discipline and restraint over acts of vengeance in reconquered areas, Iraqi militias are dogged by a reputation for sectarian violence. Such attacks have played out most frequently in areas recaptured from ISIS, where locals are often deemed ISIS sympathizers and legitimate targets. In that vein, the attacks may be considered part of a punitive response to the suspected smuggling of ISIS fighters by local bedouin in the area. The repetition of attacks targeting Sunni Arab tribes in desert areas is proof apparent that the state is unwilling or unable to reign in its allied militias, particularly when attacks strike communities whose loyalty Damascus continues to question. Ironically, if the situation continues to fester, it raises the possibility of a renewed tribal resistance to Damascus.

Key Readings

The Open Source Annex highlights key media reports, research, and primary documents that are not examined in the Syria Update. For a continuously updated collection of such records, searchable by geography, theme, and conflict actor, and curated to meet the needs of decision-makers, please see COAR’s comprehensive online search platform, Alexandrina, at the link below.

Note: These records are solely the responsibility of their creators. COAR does not necessarily endorse — or confirm — the viewpoints expressed by these sources.

U.S. and European Sanctions on Syria

What Does It Say? The report breaks down the totality of international sanctions targeting Damascus and lays out a calibrated template for progressive sanctions relief that could be offered in exchange for concessions by the Syrian regime.

Reading Between the Lines: Among many Western policy-makers, the prevailing orthodoxy concerning sanctions remains binary. However, as a policy tool, sanctions are rendered inert unless they can be deployed — and relaxed — as leverage for outcomes that are realistically achievable.

Source: Carter Center

Language: English

Date: September 2020

How does the Assad regime create and benefit from the deteriorating living conditions in Syria?

What Does It Say? The economic crisis in Syria continues to worsen, while government measures have so far allowed the black market to prosper. As a result, those closest to the regime are benefitting the most.

Reading Between the Lines: Likely, the Government of Syria is purposefully creating space for influential power-brokers loyal to it. Business elites can take over some functions of the ailing state, but neither private charitable initiatives nor humanitarian aid can adequately cover the gaps voided by the withdrawal of the state.

Source: Syria Direct

Language: English

Date: 24 September 2020

Five years after the Russian military intervention

What Does It Say? The study breaks down the impact and trajectory of Russia’s direct military intervention in Syria, five years on.

Reading Between the Lines: Russia’s military intervention is arguably the decisive turning point of the conflict. Russia’s Syria policy is a contrast to the West’s approach, and it offers a showpiece of decisive military support to a regional adversary — whatever the costs.

Source: Al Jumhuriya

Language: Arabic

Date: 30 September 2020

EU draws up options for boots on the ground in Libya

What Does It Say? If a ceasefire is declared in Libya, the EU will deploy military observers.

Reading Between the Lines: A direct EU presence in Libya could form a buffer between Turkey and Russia, but it would be a band-aid solution to a crisis that has festered up from below as a result of the collapse of Syria.

Source: Politico

Language: English

Date: 1 October 2020

Kanaker, besieged, receives the sympathy of Dar’a, and is awaiting the Tuesday deadline

What Does It Say? Following unrest and clashes in Kanaker, the Syrian government and local notables agreed to a deadline for the surrender of individuals wanted by the government in exchange for lifting the siege on the community.

Reading Between the Lines: Should the situation fail to resolve itself, it is likely that the siege will continue and Kanaker may face renewed pressure from Damascus, which has a strong incentive to make an example of the community.

Source: Al Modon

Language: Arabic

Date: 27 September 2020

How the Syrian Regime is Signaling its Openness to Peace Talks

What Does It Say? The analysis contends that some regime insiders are holding out peace with Israel as a possible off-ramp to end Syria’s pariah status.

Reading Between the Lines: There is precedent (Egypt) for regional peace deals with Israel as part of a stick-and-carrot approach to bring Arab regimes in from the cold. Syria desperately needs to end its international isolation. However, normalization with Israel would likely be only one step toward legitimating Damascus in the eyes of Washington — and further, potentially thornier, impediments remain.

Source: Center for Global Policy

Language: English

Date: 28 September 2020

Three educational curricula in northeastern Syria

What Does It Say? The Self-Administration has announced that it will be teaching three different curricula in areas under its control, one of which was approved by UNICEF.

Reading Between the Lines: Having three different curricula may be the solution to placate diverging ideologies within the ethnically diverse Self-Administration. However, there is a risk that unapproved curricula place students on a pathway that locks them out of access to the Syrian mainline university and employment pipeline in the future.

Source: Asharq Al-Awsat

Language: Arabic

Date: 28 September 2020

A new reading of the transformations in the Syrian tribal map

What Does It Say? Arab tribes in Syria were famously divided in their loyalties over the course of the conflict.

Reading Between the Lines: A tribe’s loyalty mainly depended on the benefits its members received from the government or other outside actors, furthering an age-old patronage system.

Source: Arab-Turkey

Language: Arabic

Date: 27 September 2020

The “Southern Deal” after two years … A worrying example for “Future Syria”

What Does It Say? The Government of Syria forces returned to southern Syria approximately two years ago, bringing the area back under central control, but failing to restore peace and stability with it.

Reading Between the Lines: Although the government has authority over the south, a question mark hovers over the strength of its control. In reality, the situation is complicated by daily clashes and assassinations, which have driven the area into a division of power in which Russia is now a strong hand in the area.

Source: Asharq Al-Awsat

Language: Arabic

Date: 29 September 2020

Challenges for peace in Syria without East Euphrates

What Does It Say? The area east of the Euphrates River is a major battleground in the conflict, containing much of Syria’s resource wealth.

Reading Between the Lines: Any peace deal over Syria will need to address the area, although the combination of regional power plays and international intervention will make such a solution exceedingly tricky

Source: IMPACT

Language: English

Date: September 2020

The Wartime and Post-Conflict Syria project (WPCS) is funded by the European Union and implemented through a partnership between the European University Institute (Middle East Directions Programme) and the Center for Operational Analysis and Research (COAR). WPCS will provide operational and strategic analysis to policymakers and programmers concerning prospects, challenges, trends, and policy options with respect to a conflict and post-conflict Syria. WPCS also aims to stimulate new approaches and policy responses to the Syrian conflict through a regular dialogue between researchers, policymakers and donors, and implementers, as well as to build a new network of Syrian researchers that will contribute to research informing international policy and practice related to their country.