In-Depth Analysis

Series of Strikes Show Pressures Building on Northwest Syria Aid Response

A series of attacks in northwest Syria in late March has been among the most notable conflict incidents in the region since the Turkish-Russian ceasefire agreement halted major military operations in the region more than one year ago (see: Syria Update 9 March 2020). On 21 March, media sources reported that Government of Syria forces — the Syrian Arab Army’s 46th Regiment — had targeted the surgical hospital in Al-Atareb, western Aleppo Governorate, with mortar shells. Between six and eight people were reported killed; 15 more were injured, among whom were five health care workers. The hospital itself, which was supported by the Syrian-American Medical Society (SAMS), was rendered inoperative. Relatedly, on the same day, media sources reported that Russian warplanes had targeted a cement factory and a gas plant near Sarmada and cargo vehicles in a customs yard near the Bab al-Hawa border crossing with Turkey, causing large fires and extensive damage. Qah town, near the Atma camp on the border with Turkey, was also targeted in a surface-to-surface missile attack that killed at least one person. Government forces continued to target opposition-held areas throughout the week, while opposition forces responded with mortar fire.

The attacks are some of the most notable to take place in northwest Syria — or, indeed, anywhere in the country — in the past 12 months. This fact is itself a striking demonstration of the extent to which the conflict has slowed amidst the stalemate that has descended upon Syria since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. That said, the incidents are even more important as an indicator of the tensions that continue to threaten stability in northwest Syria as well as the aid response itself. The attacks crippled infrastructure that is vital to the normal economic functionality of opposition-held areas, and they are harbingers of future humanitarian access issues in northwest Syria.

Limited attacks, large impact

Attacks by Russia or the Government of Syria targeting infrastructure in northwest Syria have been recurrent since 2018, when the region became the focal point of the Syrian Government’s major military operations. The parties have repeatedly breached the ceasefire laid down by the Turkish-Russian agreement in March 2020. Sometimes, the pretext given for such attacks has been the fact that attempts by opposition and rebel forces to block or sabotage Turkish-Russian patrols of the M5 Highway have gone unchecked. At other times, little if any justification has been provided. The latest incidents do not necessarily signal an impending large-scale military operation in northwestern Syria, but they do suggest that the region’s instability will persist. There are some who see the attacks as a deliberate effort to upend the economy and basic functionality of opposition-held areas. There is a belief that targeting such sites is part of a resource-denial campaign carried out to impose hardship on opposition areas. This narrative has gained traction amidst the economic turmoil that is now ravaging Government-held portions of Syria (see: Syria Update 15 March 2021).

At the same time, many Syrian opposition members and Western analysts have interpreted the latest string of attacks as a warning shot aimed at the international community and its continuing support to opposition-held northwest Syria. That the targeted hospital was evidently listed among the so-called “deconfliction” sites meant that its coordinates had been shared with parties to the conflict, leaving no ambiguity over its location and its use as a hospital. An attack on a site that had been so listed demonstrates the failure to protect humanitarian infrastructure in Syria. It is, implicitly, a signal of Western impotence to steer the course of military dimensions in the ongoing Syria conflict.

More importantly, the targeting also coincides with a Russian-led effort to open three new crossings between opposition-held territory and Government areas in northwest Syria. On 24 March, the Russian Defense Ministry announced the opening of three humanitarian crossings made possible by coordination between Russia and Turkey. Together with the attacks, the initiative has been read as a precursor to a widely expected Russian plan to contest the renewal of the cross-border aid authorisation at the UN Security Council in July. Currently, the resolution allows for UN cross-border aid convoys to enter northern Syria via Bab al-Hawa, the final remnant of the once expansive cross-border aid delivery mechanism in Syria. Many analysts and aid response actors fear that Moscow will wield its veto power over the renewal merely to force the capitulation of opposition areas, or with greater direction, as leverage. To what end, precisely, is unclear.

More than meets the eye

There is considerable ambiguity around the new crossing points, however. On 25 March, Turkish officials denied they had coordinated with Russia to initiate the crossings. Turkey has significant reason to support for the re-authorisation of the cross-border mechanism. From the perspective of Ankara, the collapse of the cross-border system would create pressure on its southern border. A wave of Syrian cross-border migration would likely follow, and Turkey itself would likely be forced to take on a more direct role in administering aid. While many observers have fixated on Russia’s aversion to the cross-border mechanism, they have often ignored Turkey’s capacity to cooperate with Russia on pragmatic issues of mutual self-interest in Syria. The cross-border system’s fate may well be determined by the state of Turko-Russian relations at the time the vote comes up, in July.

There are also local concerns that raise important questions for international aid actors. Media sources indicated that the local community in opposition-held Idleb has refused to allow the new, Russian-brokered crossings to open. Such communities have little incentive to welcome the introduction of a mechanism they fear is a political ploy that will ultimately be used to cut them off from the UN cross-border system, which is more transparent and expansive than an alternative controlled via Damascus. Throughout the conflict, fears such as these have combined with the geographic partitioning of the aid response to amplify zero-sum deliberations among Syrians. Regrettably, aid impartiality has been damaged as Syria’s social fabric has frayed. Not entirely without cause, Syrians sometimes view aid delivery to other areas with deep suspicion or even animosity. Some view economic hardship or the potential interruption of aid to areas held by actors with whom they differ ideologically as being justified by differences of viewpoint and the legacy of the conflict.

It is easy to dismiss the Russian crossing initiative as a push to bring greater volumes of aid under the purview of Damascus. Certainly, that is a plausible reading of the events. However, it is also worth contemplating how aid can reach Syria in a way that fosters social cohesion, rather than deepening existing divisions.

Whole of Syria Review

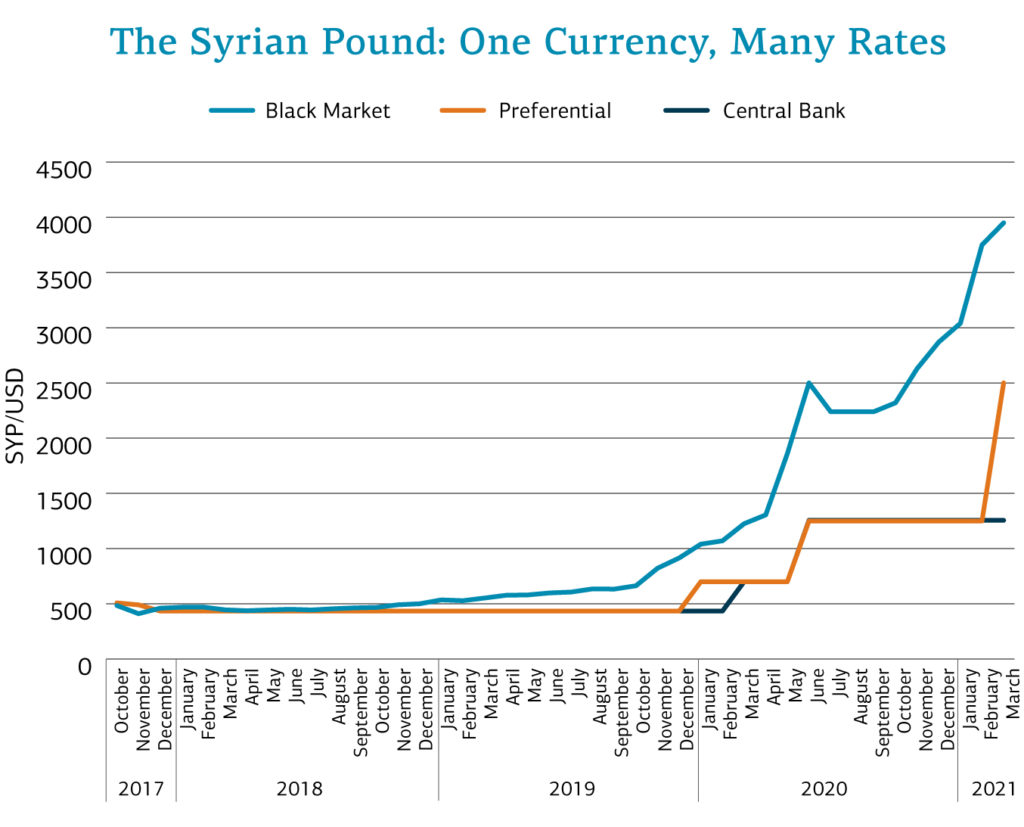

USD Conversion Rate Doubled Amid Tightening Fiscal Situation

Cell phone import suspended while money transfers face additional restrictions

Damascus: On 22 March, the Central Bank of Syria reportedly raised the so-called preferential exchange rate for international organizations and diplomatic institutions from 1,250 SYP/1 USD to 2,500 SYP. While the Central Bank had not officially announced the decision as of writing, it has confirmed this information in statements to multiple media sources, while noting that the official exchange rate will remain at 1,256 SYP/1 USD. On 23 March, the Ministry of Economy and Foreign Trade suspended the import of cell phones into Syria until further notice. On the same day, the Syrian Telecommunication and Post Regulatory Authority ceased the activation of cell phones brought into Syria by individuals from abroad for six months. Previously, individuals were able to pay a customs surcharge to activate personally imported devices for use on Syrian telecoms networks. The decision has been justified as a means to “give the priority to imports goods more essential for people’s needs”.

Holding on to the remnants

As the Syrian pound hits historic lows amid yawning swings in value (see: Syria Update 22 March 2021), the Government of Syria has introduced new economic measures to attract foreign currency from abroad and halt the drain of foreign currency drain from the country. Modifying the preferential exchange rate is, ostensibly, an incentive to attract money from abroad. The change will have an impact on aid activities, but it will not allay concerns among donors that money flowing into Syria loses a considerable portion of its value due to the wide spread between conversion rates. Given current trajectories, this gap will only widen over time (see: figure 1).

Banning the import of luxury items such as cellphones — and, well before that, cars (in May 2011) — is a step that likely aims to preserve precious foreign currency reserves needed for strategic imports of basic goods. Furthermore, the Government has followed a heavy-handed approach to the money transfer sector, including shutting down hawala offices and arresting people transferring money on the black market or using foreign currencies in their general trading activities. Media sources reported that the Government of Syria will begin imposing previously announced restrictions on moving money between governorates. The reported aim is to confine large transfers to banks, heightening the monitoring of the financial transactions of companies and individuals. However, the growing gap between official and black-market exchange rates along with the reluctance of the central bank to amend the exchange rates accordingly is increasingly pushing people toward informal channels to undertake their financial transactions and transfers. The security-forward approach of the Government has thus far failed to stop economic deterioration or deter informal financial transactions, especially given that security forces are reportedly deeply involved in black-market activities.

Source: Syria Report and Central Bank of Syria

Facing COVID-19 Surge, Lebanese Health Minister Turns to Syria for Oxygen

The deal raises eyebrows but highlights long-standing links between neighbours

Damascus: On 24 March, Lebanese Minister of Health Hamad Hasan traveled to Damascus to secure oxygen for hospitalized COVID-19 patients in Lebanon. The Lebanese Ministry of Public Health (MoPH) reported a possible shortage of oxygen in hospitals after a Turkish ship carrying oxygen to Lebanon was unable to dock due to inclement weather last week. The Health Minister secured enough oxygen to supply hospitals for three days at a rate of 25 tonnes per day. Meanwhile, two batches of oxygen were set to arrive in Lebanon starting on Monday 29 March, although their arrival was unclear as of writing.

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, both Lebanon and Syria were able to independently meet their own oxygen needs, but the increased demand for therapeutic oxygen since the pandemic has pushed Lebanon to import supplies from Turkey and Syria. While oxygen is generally available in both Syria and Lebanon, it has been pushed to an increasingly expensive private market in recent months, like many resources caught up in the economic crises roiling both countries.

Political stunt or a stopgap solution?

The deal sparked suspicion and frustration on both sides of the border. Basic health services have been pushed increasingly out of the reach of those who lack the necessary cash or connections in both Syria and Lebanon. After the likelihood of a true oxygen shortage was brought into question, Lebanese media speculated whether the health minister’s PR-heavy trip to Syria was a politically motivated attempt to shore up perceptions of President al-Assad in Lebanon, and only secondarily to fill gaps in oxygen supplies.

Whether politically motivated or a quick fix to a much larger problem, the deal highlights the interconnected nature of politics, economics, and — more recently — crises in Syria and Lebanon. As each country becomes more isolated from the regional and international stage, such linkages are likely to deepen and become more public. To that end, the deal also highlights the difficulty, and likewise the strategic shortcomings, of assessing the ensuing crises in Lebanon or Syria as separate cases rather than dynamic and increasingly interconnected developments.

People’s Assembly Approves Law to Turn Private Cars into Taxis

The law aims to provide livelihoods and fix the transit gap

Damascus: On 23 March, media sources reported that the People’s Assembly approved a draft law for the Ministry of Public Transportation that would allow small and medium passenger vehicles to be registered for use as taxis. Reportedly, such vehicles will be allowed to carry up to 10 passengers. According to officials quoted in local reports, this decision was taken in order to ease transport between and within governorates, as well as in the countryside of various provinces.

Public transit gridlock

The traffic situation in Syria has progressively worsened, with congestion, infrastructural damage, crowding, and rising petrol prices in particular confounding public transit systems. The law may aim to kill two birds with one stone. Not only are municipal and inter-governorate public transit issues growing more problematic, but the lack of sustainable livelihoods means that Syrians are increasingly being pushed to take on supplemental income-generating activities. In other words, even Syrians with full-time jobs are being driven into the gig economy. Clearing the path for them to work as public transit drivers addresses both concerns, albeit in a worrying way. The measure prompts a chilling recollection of the career downshift seen in 1990s Iraq among skilled technicians and educated workers, who took on work as menial laborers while sanctions battered the economy. Without viable opportunities, doctors, engineers, teachers, and state employees were driven to menial labour, including as taxi drivers. Local sources note that Syrians have long used their private vehicles as a form of unlicensed quasi-public transportation, yet they risked running afoul of the authorities for doing so. The new law not only eliminates this risk, it makes ordinary Syrians responsible for filling the gaps created by the state’s inadequate support for public transit.

‘Internal’ Opposition Vies, Unsuccessfully, for Platform in Damascus

Opposition attempts to unify, tribal leaders endorse al-Assad’s candidacy

Damascus: On 23 March, Syrian opposition figures in Government-held areas announced the initiation of a political umbrella movement representing the political opposition inside Syria, called the National Democratic Front (al-Jabhat al-Wataniyyah al-Demouqratiyyah, or JOD). The entity aims to unify the Syrian opposition to achieve political transition under the terms of UN Security Council Resolution 2254, oust all foreign forces from Syria, and dismantle the Syrian security state. However, on 27 March, media sources reported that the conference to launch the platform had been called off after the Government of Syria banned the meeting.

Of note, the JOD had been announced by Hassan Abdel Azim, head of the National Coordination Committee for Democratic Change (NCC). The NCC consists of a number of political parties, such as the Democratic Arab Socialist Union, Arab Revolutionary Workers Party, Communist Labour Party, Arab Socialist Movement, and Democratic Union Party. Other parties invited to attend JOD’s inaugural conference in Damascus included the Syrian Communist Party (Political Bureau), the Kurdish Progressive Party, the Kurdish Union Party, and the Turkmen Movement, among others. It is worth noting that neither the Syrian Democratic Council (SDC) nor the National Coalition for Syrian Revolutionary and Opposition Forces (Etilaf) was included.

In the shadow of the presidential election

Events like the proposed opposition conference have not taken place in Government of Syria–controlled areas since the outbreak of the conflict. It is unclear whether the initial latitude afforded the NCC to plan the conference was due to anticipated Government acceptance of a superficial opposition prior to the upcoming presidential election, or a result of Russian protection. In either case, the preparations were fruitless, and the Government of Syria was unwilling to countenance an initiative aiming for political transition or power sharing. The efforts of the participating political parties from among the so-called “internal opposition” (as opposed to the “external opposition”, represented by Etilaf), may appear to give a boost to efforts to unify the fractious Syrian opposition. However, it is also possible to view this as a setback to efforts to build stronger links between external and internal opposition entities and the SDC, the political counterpart to the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF). These efforts have become more challenging as the rift between these actors deepens over fundamental issues such as the relationship with the Assad regime and cooperation with Russia.

It is also notable that, although the JOD attempted to decouple the initiative from Syria’s upcoming presidential election, the two events cannot be viewed in total isolation. Ahmad Asrawi, the head of the Democratic Arab Socialist Union, stressed that the planned conference bore no relation to the upcoming presidential election, as per NCC’s established stance to boycott the election. That may be true, but the Government of Syria is seemingly content to avoid political dialogue. Instead, with the election approaching, there have been more public efforts for popular mobilisation. To that end, tribal conferences have recently taken place in Deir-ez-Zor and Al-Hasakeh governorates, attended by tribal figures and Government-affiliated political and security figures, to endorse the candidacy of Bashar al-Assad in the next presidential election. There is a pervasive sense that al-Assad has not yet declared his intention to stand in the elections in order to create pressure for “spontaneous” public displays of support, lending his candidacy greater legitimacy as the inevitable response to the popular will. The opening for candidacy announcements is expected sometime between April and May. That said, there is also a possibility that the election will be postponed “due to the COVID-19 outbreak,” as Riyad Haddad, the Syrian ambassador to Russia, has indicated.

IS Prison Break in SDF-Held Deir-ez-Zor

Tunnel dug in prison bathroom; number of fugitives is contested

Sur, Deir-ez-Zor Governorate: Media sources reported that on 21 March, 11 prisoners with suspected links to Islamic State (IS) escaped from a Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) prison in the northern countryside of Deir-ez-Zor. Reportedly, the prisoners escaped by digging a tunnel through one of the prison bathrooms. Local sources confirmed that some prisoners did escape the prison; however, they reported that only five or six prisoners were involved. The SDF reportedly arrested a number of its own members for interrogation after the incident.

Prison break

Although major IS activity has decreased significantly since the group’s territorial defeat almost exactly two years ago, in March 2019, its members, affiliates, and sympathisers continue to have an active presence — in the form of sleeper cells — across the Syrian hinterlands. The escape of suspected IS members is of concern, but its salience for the aid response is more closely related to the issue of IS-linked detainees in northeast Syria. On 23 March, Human Rights Watch published a scathing indictment of the Self-Administration and foreign governments alike for their collective failure to fairly try, release, or repatriate the 43,000 foreigners, including women and children, who are suspected of IS links or were rounded up in the waning days of IS rule, and are now detained in camps and prisons in northeast Syria. The fate of these individuals is a major question on which little substantive progress has been made. The SDF has repeatedly threatened to release detainees if it does not secure greater support for its civil and administrative apparatuses. Events such as this prison break will become more probable over time, particularly if the SDF is searching for pressure points to gain international attention.

Open-Source Annex

Key Readings

Key Readings

The Open Source Annex highlights key media reports, research, and primary documents that are not examined in the Syria Update. For a continuously updated collection of such records, searchable by geography, theme, and conflict actor, and curated to meet the needs of decision-makers, please see COAR’s comprehensive online search platform, Alexandrina, at the link below..

Note: These records are solely the responsibility of their creators. COAR does not necessarily endorse — or confirm — the viewpoints expressed by these sources.

The Kin Who Count: Mapping Raqqa’s Tribal Topology

What Does it Say? The article outlines the complex tribal structure in Ar-Raqqa Governorate.

Reading Between the Lines: The complex nature of tribes in eastern Syria, including the definition of who “counts” as a tribesman, is confusing to outsiders, leading to false links between tribalism and terrorism.

Source: Operations and Policy Center

Language: English

Date: 24 March 2021

How Putin Is Starving Syria — and What Biden Can Do

What Does it Say? The article argues for the international community to pressure Russia via sanctions and UN procedural maneuvers to withhold its veto from renewal of the cross-border authorisation.

Reading Between the Lines: While there is no doubt that renewal of the authorisation is an urgent necessity for reaching northwest Syria’s 4.5 million people, keeping open the crossing will likely require a combination of positive incentives and compromise that punitive sanctions alone cannot provide.

Source: Politico

Language: English

Date: 24 March 2021

What Does it Say? The interactive timeline shows how, after 10 years of conflict, the vast majority of Syrian refugees still remain in limbo. Of the roughly 6.6 million registered refugees, only 201,000 have been resettled in other countries through the UN resettlement program.

Reading Between the Lines: Two things are clear by taking a long look at the Syrian displacement crisis. The first is the UN’s ability to influence the international community concerning refugee acceptance is minimal. The second is that the pressure to find alternate strategies to deal with refugee outflows has given rise to a costly and morally dubious international refugee bureaucracy in which truly durable solutions remain elusive.

Source: The New Humanitarian

Language: English

Date: 17 March 2021

Expanding Humanitarian Assistance to Syrians: Two Deadlines Approaching

What Does it Say? The article presents a good summary of the issues surrounding cross-border aid mechanism renewal.

Reading Between the Lines: While politicking over cross border aid is inevitable, Russia is less likely to push for the end to the cross-border aid system than many analysts assume. It is important to recall that Russia is Turkey’s partner in Syria, and the nature of that relationship will shape the outcome of the cross-border resolution. Renewal is not guaranteed, but neither is a Russian veto.

Source: The Washington Institute for Near East Policy

Language: English

Date: 23 March 2021

Death Funded by Death: Southern Syria Lost in the Drug Limbo

What Does it Say? Drug-related incidents have increased in southern Syria, giving rise to other crimes, including murders.

Reading Between the Lines: The long years of war have opened up space for drug traffickers to ply their trade in Syria, and it is ordinary citizens who pay the price — falling into despair and turning to drugs for livelihoods and as an escape.

Source: Enab Baladi

Language: English

Date: 22 March 2021

Thousands of Foreigners Unlawfully Held in NE Syria

What Does it Say? The report decries the fact that 43,000 foreigners, many of them suspected of links to IS, are reportedly still detained in Syrian camps in inhumane conditions, with no access to due process. Of these prisoners, 27,500 are children.

Reading Between the Lines: The report highlights the failure of the international community to repatriate and take responsibility for their own nationals now held in northeast Syria; meanwhile, the SDF has also deprioritised resolving the issue, at least in part due to international indifference.

Source: Human Rights Watch

Language: English

Date: 23 March 2021

The Situation in Kafariya: Interview

What Does it Say? Internally displaced people have been moving to Kafariya, a village in northern Syria, due to the low rents there. However, NGOs have largely avoided the area over fears of violating property rights.

Reading Between the Lines: The community was one of four involved in a deeply contested population transfer scheme that relocated besieged populations from four towns in different areas of Syria.

Source: Aymenn Jawad Al-Tamimi

Language: English

Date: 24 March 2021

Insecurity in Southern Syria: Tracking Daraa, Quneitra and Suwayda (January – February 2021)

What Does it Say? An article explaining the complex security situation in southern Syria over the first three months of 2021.

Reading Between the Lines: Southern Syria is an exceedingly complicated area. Reconciliation deals are constantly breached and assassinations have become the norm. Restoring the rule of law in the south will require a qualitative shift in the services, administrative, legal, and security situation. Suich a shift appears, for now, improbable.

Source: Center for Middle Eastern Studies

Language: English

Date: 25 March 2021