In-Depth Analysis

Brussels V: No Surprises as Donors Embrace Syria Status Quo

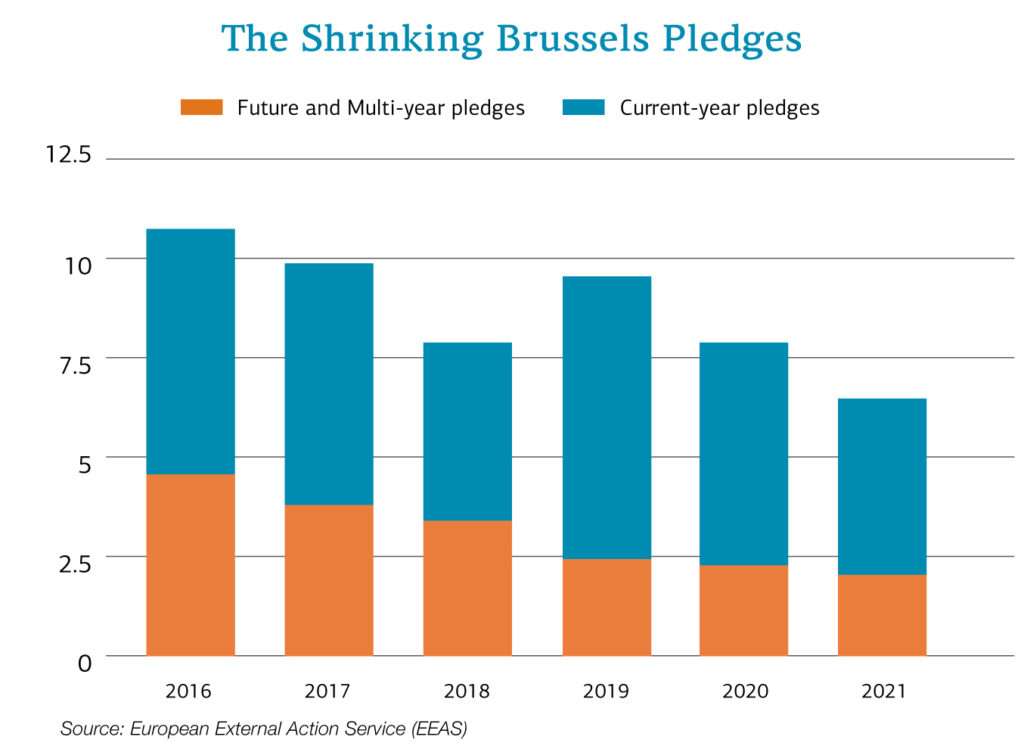

The Brussels conference came to a close on 30 March, with donor countries pledging 4.4 billion USD in funding to the Syria response in 2021, plus an additional 7 billion USD in conditional loans. A further 2.2 billion USD in funding was pledged for 2022. The pledges came several billion dollars short of the UN appeal, which sought over 10 billion USD for the Syria response, which is traditionally split among: neighbouring countries (the 3RP response), humanitarian funding inside Syria (HRP), and the ICRC Syria Crisis appeal. While the pledges were more than a billion dollars less than the amount staked in 2020, Germany made headlines by increasing its support to 2 billion USD overall, taking the lead as the top single donor in the conference.

To many involved in the Syria aid response, the Brussels conference was a disappointment, highlighting that the Syria crisis is increasingly out of sight and out of mind (see: Syria Update 15 March 2021). The reduction in funding comes as little surprise, however: donor fatigue toward Syria has only been accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic and the financial challenges it has visited upon donor governments at home. What remains to be seen is how the shrinking pool of funds available to the Syria response will be split sectorally and geographically. Important questions remain over distribution across Syria’s regions and to increasingly unstable neighbouring countries that host substantial Syrian refugee populations. Such details will be resolved at a later stage, likely in September, alongside allocations of funding designated through the UN or directly between donors and partners.

The institutionalisation of a crisis

Much like the muted diplomatic statements made earlier in March in recognition of the 10-year-anniversary of the popular uprising in Syria, the Brussels conference highlights that the international community continues to struggle to articulate realistic intermediate-term goals in Syria. For European donors, pledges came alongside opinion pieces restating political priorities that have remained largely unchanged despite evolving realities on the ground. Rhetoric and reality do not necessarily align, and critics would argue that the West’s all-or-nothing objectives in Syria are increasingly unattainable. That said, the pledges made in Brussels are no doubt significant. The conference recommits donors to aiding the Syrian people. Although pledges have shrunk, the largesse is no doubt commendable. However, the funding shortfall is also significant. There is a perverse irony in the fact that even as conflict has ebbed over the past year, Syria has veered further into crisis, with over 13 million people in need of aid inside Syria, in addition to more than 5 million Syrians in the wider region.

Regional actors also continue to vocalise their priorities as they attempt to force donors to pay greater heed to regional refugee-support needs. On 15 March, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan wrote an op-ed in which he credited Turkish military intervention with preventing a humanitarian catastrophe in northwest Syria. Erdogan averred that “restoring peace and stability in the region depends on genuine and strong Western support for Turkey.” Lebanese President Michel Aoun likewise met with the UNHCR Representative in Beirut last week. The embattled Lebanese president used the audience to reiterate the purported negative impact Syrian refugees have on Lebanon’s economy, a long-standing political talking point now being recycled to distract from the Lebanese government’s ineptitude and incapacity to halt Lebanon’s economic implosion. These are predictable calls for attention, but they are notable all the same: both Turkey and Lebanon are volatile, and both are liable to use their centrality to Western approaches to Syria as leverage for more donor support.

It is notable that the conference has seemingly transformed from a collaborative discussion platform about priority steps to achieving a more just and prosperous future for Syria to a stage for donors to double down on their political priorities. Local sources indicate that less attention has been paid to genuine cooperation between donors and civil society actors. To that end, the secondary role for civil society organisations during the so-called Day of Dialogue in Brussels shows the limitations of the aid serctor’s localisation agenda. Although donors have sought to make good on their promise to incorporate local civil society into decision-making processes, some Syrian civil society actors said they were sidelined at Brussels. Civil society groups reported receiving short notice of conference scheduling and preparatory sessions, and some claimed to be rushed to produce materials and to arrange discussions meant to inform the larger conference. In some cases, the mismatch between the expectations of local Syrian civil society and donors and policymakers risked being outright harmful. Some participants in the conference expressed frustration with the final session of the Day of Dialogue, in which former detainees were asked to share their own personal experiences in detention and discuss accountability — a growing donor interest — at a conference that is supposed to be dedicated primarily to unrelated matters concerning humanitarian funding.

Dynamics such as these have fostered fatigue at all levels: Western donors are in an unenviable position, and they are involved in a hard-fought struggle to devise impactful aid policy amid rapidly deteriorating conditions and stagnant political objectives. Grassroots civil society is faced with shrinking space for productive advocacy to move on from the status quo. Squaring different viewpoints with each camp will be critical to a more effective and impactful aid in Syria in the long term.

Whole of Syria Review

Massive ‘Humanity and Security’ Campaign Sweeps through Al-Hol Camp

Low hopes of bringing security to al-Hol

Al-Hol camp, Al-Hasakeh Governorate: On 28 March, the Asayish (the Self-Administration’s internal security service) announced the beginning of a security campaign inside al-Hol camp, which it launched to “eliminate the influence of Islamic State within the camp”. More than 5,000 personnel from the Self-Administration’s various security forces participated in the sweep of the camp, including members of the People’s Protection Units (YPG), Women’s Protection Units (YPJ), and Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF). Around 125 suspected Islamic State (IS) members or affiliates (mainly Iraqis) had been arrested by the end of the first phase of the campaign on 2 April, including religious leaders and security figures such as Abu Muhammad Al-Jamili (62), Mustafa Khalaf (18), and Ali Khlaif (19). According to Ali Hassan, spokesperson for the Asayish, small tunnels were discovered, and communication devices including mobile phones and laptops, were confiscated during the campaign, which was labeled “Humanity and Security” by security forces.

Security solutions for humanitarian and legal crises

The campaign is one of the largest security campaigns ever carried out in al-Hol. It is especially notable that, in addition to targeting sections housing non-Syrian residents, as is usual — given this demographic’s general association with security incidents — it also covered Syrian sections. Moreover, the sweep was carried out against the backdrop of a communications blackout, as internet and cell coverage of the camp were cut. Residents affected by the sweep were relocated to an interim shelter outside the camp before being sent back to their tents.

The security conditions in the camp have deteriorated sharply since the beginning of the year. According to Asayish spokesperson Hassan, more than 47 people have been killed in the camp in the first three months of 2021 — a troubling jump compared to the 40 killings in all of 2020. As the security campaign’s name suggests, there is an explicit link between security deterioration and humanitarian conditions inside the camp, particularly as some NGOs have suspended their activities in al-Hol out of concern for the safety of personnel and operational security. On 2 March, for instance, Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) announced the suspension its operations in the camp following the death of MSF personnel (see: Syria Update 8 March 2021). On 25 March, UNICEF warned of the “urgent need” to reintegrate or repatriate children stuck in al-Hol due to squalid and unsafe conditions, echoing the charge made by a UN special rapporteur that camp conditions are so dire they may constitute torture (see: Syria Update 15 February 2021).

The deteriorating security in the camp can be traced to three main factors: inhumane living conditions and a lack of basic services; the security-forward approach to dealing with the camp’s roughly 62,000 residents, of whom more than 80 percent are women and children (as of February 2021); and the deadlock with respect to repatriation and reintegration of residents. While all three prongs can be addressed in some capacity, from a donor perspective, the most pressing is repatriation. Since October 2020, there has been a modest acceleration in the release of Syrians from the camp (see: Syria Update 12 October 2020). However, the issue of foreign residents is far thornier, as most countries remain reluctant to repatriate their nationals. For instance, on 30 March, Danish media reported that the Danish government had appointed a committee to deal with 19 children in northeast Syria camps who may be eligible for repatriation to Denmark, while apparently denying the same pathway to six women with Danish citizenship (although three have reportedly been stripped of citizenship). Although domestic political pressures are intense, states must be wary of such approaches. Returning children without their mothers is likely to complicate reintegration and socialisation in their home countries. Moreover, leaving nationals in legal limbo in Syria merely transfers responsibility — in this case to the already overburdened and under-resourced Self-Administration authorities.

Anecdotally, local sources inside the camp and among former residents note that security measures imposed on the camp population compound a generalised sense of despair among residents, thus fueling grievances against the Self-Administration and aloof or disinterested foreign governments. Humanitarian, social, and legal solutions must be marshaled on several fronts to: improve humanitarian conditions inside the camp, which will mitigate vulnerability to radicalism; implement livelihood and integration programs for Syrians in their communities of origin; and, most importantly, repatriate foreign citizens, especially children and those who are not credibly accused of crimes. In cases where crimes are suspected, innovative legal approaches may be necessary. It is vital that the international community not allow al-Hol to become a legal black box where the rule of law is disregarded out of deference to parochial political interests.

Fuel Crisis Grips Damascus: GoS Blames Suez Blockage

Amid the acute fuel crisis in Syria, gasoline rations are slashed in half

Damascus: On 31 March, the Government of Syria slashed the motor vehicle fuel allocation in half, amid a crippling fuel shortage that has left many of Syria’s busiest thoroughfares all but empty of vehicle traffic. A Damascus Governorate official told local media that rations had been reduced to 20 liters every seven days for private cars, and 20 liters every four days for taxis and for vehicles traveling to Lebanon and Jordan. The reduction is said to be temporary, until the arrival of additional oil shipments. The Syrian Ministry of Oil has stated that the blockage in the Suez Canal had impeded oil supplies to Syria, leading to “the delay in the arrival of a tanker carrying oil and oil products to the country.” The ministry stated that fuel is being rationed to allow essential services — including bakeries, hospitals, water, and telecommunications — to continue operations. As a result of the interruption, long fuel station queues have returned in Damascus and its suburbs; people hoping to fill their vehicles with gasoline have to wait for long hours at petrol stations, and local sources in Government-held areas share anecdotal reports of fuel being unavailable at any price.

The Suez blockage is not the sole factor

The acute fuel shortage likely has been brought on by the interruption of marine traffic in the Suez Canal. However, attributing the crisis to this event alone would miss the larger point. Fuel crises have consumed Syrians’ daily lives regularly since spring 2019, and intermittently for much longer. In mid-March, the Syrian government raised petrol prices by more than 50 percent after the Syrian pound hit record lows on the black market. The liter cost of subsidised fuel jumped from 475 to 750 SYP (17 cents USD, at black market rates). Acute crises such as the one now gripping Syria can be linked to global events, but the Syrian Government has repeatedly increased fuel prices in recent years in response to the accelerating economic collapse brought on by 10 years of conflict, isolating sanctions, and the COVID-19 pandemic, among other factors. Meanwhile, relief from Syria’s current shortage is reportedly in sight. Tanker-tracking specialists have identified a flotilla of Iranian oil tankers bound for Syria. The current crisis demonstrates the fragility of the Syrian-Iranian oil lifeline.

Across Syria’s three regions, fuel availability and costs vary widely. In the northwest, the HTS-linked WATAD company has recently increased the price of fuel for the fourth time since November 2020, attributing the increase to the Turkish lira’s slipping value against the U.S. dollar. Therefore, fuel is generally available, but expensive. Meanwhile, and despite holding most of Syria’s oil reserves, northeast Syria is also facing a fuel shortage, as the Self-Administration reportedly cannot produce and refine enough oil and gas to meet the demand of the civilian population, which accuses officials of corruption and inequitable distribution. While fuel is often cheapest in northeast Syria, its availability is variable. Donors and aid implementers should bear in mind such regional variations when devising interventions.

COVID-19 Patients Transferred as Damascus Hospitals Reach Capacity

1 million vaccine doses to reach Syria, though distribution will be slanted

Damascus: On 30 March, media sources reported that the Government of Syria had begun transferring COVID-19 patients from Damascus city to medical facilities in Rural Damascus and Homs governorates because Damascus hospitals are full. Reportedly, hospitals are now turning suspected COVID-19 cases away, due to a lack of intake capacity.

A drop in the bucket

The transfer of patients from Damascus to hospitals in outlying areas is a worrying sign of COVID-19’s unchecked spread in Syria, as another wave of infections seemingly sweeps over the country. In part, these conditions are a predictable consequence of the Government of Syria’s decision to forgo strict enforcement of COVID-prevention protocols. Inside Syria, rumours now abound that the Government may impose restrictive measures during the upcoming Ramadan season — as it did last year, shortly after the pandemic’s initial outbreak. However, the Syrian Government finds itself in a delicate position. Not only would restrictions damage an already battered economy, but the socio-political risk is also high. To impose restrictions on an already aggrieved population is to invite potentially destabilising acts of defiance (see: Syrian Public Health after COVID-19: Entry Points and Lessons Learned from the Pandemic Response). Resistance is especially likely given Syrians’ moderate levels of knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding COVID-19. Denial on the part of authorities is also a factor. That said, the Ministry of Education has reportedly closed schools and universities due to COVID-19 cases. This may be a harbinger of further closures to come.

Syrians to get the vaccine — but access depends on location

Meanwhile, there is little more than a pinprick of light at the end of the tunnel, in terms of the pandemic’s end. The impending arrival of the first major batch of COVID-19 vaccines to Syria was reported in mid-March. According to a WHO official, Syria will receive 1 million doses of the AstraZeneca vaccine via the COVAX facility as early as late April, although this schedule is in doubt. Of the 1 million doses, 336,000 will be delivered to northwest Syria through the cross-border mechanism. A mere 90,000 doses will reach the northeast, while the vast majority of doses will be delivered to Government of Syria–held areas. This troubling imbalance in vaccine delivery confirms the worst fears raised by aid actors raised when the Ya’robiyah border crossing closed in early 2020. In response, civil society organisations in northeast Syria have banded together to warn that that vaccines will disproportionately populations of Government-held areas. A similar fate could await the northwest if the Bab al-Hawa crossing is also shuttered.

Syria has long been a place of split-screen realities. Crippling poverty has existed alongside immense fortunes built on exploitation and extraction. The pandemic has provided plenty of further examples of this dissonance. The grim indicators concerning hospital capacity and partial vaccine distribution stand in stark contrast to the news that Syrian President Bashar al-Assad and his wife, Asma, have now recovered from COVID-19, following news of their recent diagnosis.

Syrian Pound Snaps Back, Yet Relief Will Be Short Lived

Over the long term, the SYP is only likely to depreciate

Damascus: The Syrian pound (SYP) has rallied as the dollar exchange rate has dropped from 4,700 SYP/USD on 17 March to 3,400 SYP/USD as of writing, on 28 March. Government of Syria Minister of Finance Kinan Yaghi reportedly stated that the high exchange rates to which Syrians have had to become accustomed are a result of “psychological warfare managed from outside and speculation from within.”

Psychological warfare

Naturally, the most pertinent question concerning the currency’s unanticipated appreciation is the cause of this sudden fluctuation. No single, definitive answer is apparent. For its part, the Government of Syria has long claimed that speculators and manipulators are behind the collapse of the pound’s value in recent years. No doubt, psychological pressures are part of the equation. Local sources have indicated that limited money supply may have created the appearance of increased demand for the pound, although this is difficult to assess. In response to this appreciation, local sources report that sticker prices of market goods have decreased between 10-15 percent. Meanwhile, the Government of Syria has also reported that it will settle on a new approach to state salaries after the month of Ramadan. As of writing, it has given no concrete indication of what this will mean in real terms.

Russia Suspends Operation of Crossing Points in Idleb and Aleppo

Crossing points are closed again; Russia’s response is now in question

Idleb and Aleppo governorates: On 29 March, Alexander Karpov, the deputy head of the Russian Reconciliation Center for Syria, announced that Russia had suspended the operation of the three crossing points between northwest Syria and Government-held territory that were opened last week in Saraqab, Abu Zendin, and Mezanaz, due to insecurity. One day earlier, the center took aim at opposition forces for thwarting the crossings, claiming the latter had deliberately prevented civilians from leaving northwest Syria for Government areas. On 22 March, Karpov said that opposition forces had carried out at least 40 attacks on the de-escalation zone in Idleb Governorate. Naji Mustafa, a spokesperson for the National Front for Liberation, stated that, as of 30 March, no civilians had been recorded leaving via the crossing points for Government-controlled areas. It is worth noting that the Turkish government denied reaching an agreement with Russia over the operation of the three crossing points, while the Syrian Interim Government was also emphatic about its refusal to coordinate any crossings with Government of Syria-controlled areas.

Security, economic, and political calculations

Whether the suspension of crossing points is due to security conditions or the refusal of local and regional actors to cooperate, Russia has once more failed to link opposition- and Government-controlled areas. Such efforts have been a Russian priority in recent months, which some suspect is a pressure tactic against the UN cross-border system now concentrated at Bab al-Hawa. Anticipating the consequences of this latest failure may be more important than explaining its causes. In the past, Russia has followed-up such disappointments by escalating its military attacks on targets in Idleb and Aleppo, including civilian sites, such as markets and hospitals (see: Syria Update 29 March 2021). Some in the Syria-focused aid community have questioned whether Moscow’s now-abandoned plan to open the crossings was related to the renewal of the cross-border aid authorisation, which is set for a vote at the UN Security Council in July. Russia has sent clear signals that it will resist calls for expansion of the current authorisation. As the vote approaches and Russia seeks additional pressure to undermine the UN cross-border resolution, it is likely to make bolder attempts to chip away at the existing cross-border aid system. On 30 March, Russian Deputy UN Representative Dmitry Polyanskiy reiterated Russia’s long-standing position that the cross-border system infringes on Syria’s territorial integrity, calling it a “very gray scheme.” Further attempts to open crossings that link opposition- and Government-held areas are likely, even though Russia will likely seek to present opposition factions as the greatest impediment to successful cross-line aid delivery.

Dar’a: 4th Division Expands Southern Presence, Insecurity Increases

Quneitra also sees instability; As-Sweida diaspora bids for autonomy

Mzeireb, Dar’a Governorate: On 28 March, local and media sources reported that the 4th Division had sent military reinforcement to western Dar’a Governorate. Local sources indicated that the reinforcements included military vehicles and personnel carriers, and they bolstered military positions recently taken over by the 4th Division between Yadudeh and Mzeireb, near Tafas, and on the road between Dar’a city and the western Dar’a countryside (see: Syria Update 15 February 2021).

Capitalising on chaos

All parties present in southern Syria continue to vie for greater influence, but it is the 4th Division that has seemingly enjoyed the greatest success in recent months, particularly in western Dar’a. The 4th Division has capitalised on the repeated targeting of its forces and the presence of unreconciled former opposition commanders as a pretext for its continued expansion. The Central Committee — a negotiations platform created to bridge opposition areas and central authorities — continues to maintain a parallel line of communications with the 4th Division, Russian forces, and Government of Syria security forces in an effort to prevent tensions from breaking out into major clashes or further sieges. Nonetheless, insecurity runs deep. In March, Dar’a recorded the killing of more than 60 people, many as a result of assassinations.

Fluid security conditions in the south are not limited to Dar’a. In neighbouring Quneitra Governorate, media sources reported on 27 March that Military Security personnel, 4th Division fighters, and local militias had been targeted in several security incidents. On top of the already fragile relationship between the Syrian Government and reconciled communities in Quneitra, tensions persist over local influence and rumours about the growth of an IS presence — a concern that is shared across governorate lines in southern Syria (see: Syria Update 22 March 2021). Meanwhile, in As-Sweida Governorate, the community’s independent streak continues to cause friction with Damascus. Media sources indicated that some in the diaspora have advocated for the formalisation of self-rule in the area, albeit with little overt support on the ground. Local armed groups reportedly blocked the attempt to form a military faction as the nucleus of a self-protection and self-administration project in Sweida. Despite the lack of uptake locally, such efforts reflect the region’s fiercely independent streak, and they portend continued instability for the foreseeable future. They are, moreover, notable as indicators of the pressures inside Syria to cede greater local control to the community level. As the quality of state service provision weakens, pressures such as these will grow.

Open-Source Annex

Key Readings

Key Readings

The Open Source Annex highlights key media reports, research, and primary documents that are not examined in the Syria Update. For a continuously updated collection of such records, searchable by geography, theme, and conflict actor, and curated to meet the needs of decision-makers, please see COAR’s comprehensive online search platform, Alexandrina, at the link below..

Note: These records are solely the responsibility of their creators. COAR does not necessarily endorse — or confirm — the viewpoints expressed by these sources.

What Does It Say? The article details how cryptocurrencies are used to funding armed groups in Idleb. Although the U.S. has linked several to terror-financing operations, local actors continue to find ways to side-step these impediments.

Reading Between the Lines: Transferring monetary value without the encumbrance of physically moving money is a chief concern that is — ironically — shared by armed groups and aid actors alike. Armed group financing is particularly thorny, but the impact of sanctions increases the pressure to find safe haven in secure digital tools.

What Does It Say? An examination of how Syria has dealt with the COVID-19 pandemic.

Reading Between the Lines: Syria’s health infrastructure has been heavily damaged by the conflict; moreover, many health practitioners have left the country and those remaining have limited access to proper protective gear, medical supplies, and treatments.

What Does It Say? Hama Governorate will be experimenting with a new system to distribute bread: each person will receive 10 packages of bread per month.

Reading Between the Lines: Hama is among the areas of Syria that has seen protests over bread distribution. The struggle to supply Syrians with bread — a staple food item — sustainably, has been among the chief causes of popular unrest in recent months.

What Does It Say? A new study has reignited the call to change the way sanctions in Syria work.

Reading Between the Lines: Syria is perhaps the most visible manifestation of the increasing debate over the use (and abuse) of sanctions and whether they can be made more effective, targeted, or ‘smart’.

What Does It Say? The letter by Syrian organisations implores Bashar al-Assad to engage in meaningful dialogue with the West in order to end sanctions on the country.

Reading Between the Lines: The Government of Syria has made very clear that their views and those of the West differ widely; it is unlikely that they will come to an agreement any time soon. The Assad regime continues to privilege its own survival (the nominal cause of sanctions) over the well-being of the civilian population.

What Does It Say? The report details how some are taking advantage of Syria’s outdated HLP system to swindle people out of their homes and property.

Reading Between the Lines: HLP issues are a chief concern of the Syria response, but as the article makes clear, abuse of the system is not limited to state officials. Individuals, too, can take advantage while dispossessing fellow Syrians.

What Does It Say? The article details how Self-Administration officials have faced threats and assassination attempts in Deir-ez-Zor.

Reading Between the Lines: SDF-held Deir-ez-Zor has been among the hotspots of conflict and instability in northeast Syria, with Arab tribes largely unhappy with the way the SDF conducts itself. Stabilising these communities will depend on greater local buy-in, which is likely impossible without stronger efforts to combat corruption and resource mismanagement.