In-Depth Analysis

On 12 June, local and media sources reported that at least 22 people were killed and 50 injured in a two-part rocket attack in Afrin city, northern Aleppo Governorate. The first salvo targeted residential neighbourhoods and was followed by an attack on Shifa’a Hospital, which had received many of the victims of the first barrage. Among the reported casualties were at least three healthcare workers. The hospital, which is supported by the Syrian-American Medical Society (SAMS), has since been taken out of service. Turkish Armed Forces accused the Kurdish People’s Protection Units (YPG) and Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) of carrying out the attack and, in response, on 13 June, shelled three sites they claimed belonged to the groups in the Kurdish-held area of Tel Refaat, roughly 10 km east of Afrin.

At the time of writing, it is not clear who carried out the attack — one of the deadliest in northwest Syria in recent memory. The incident follows the partial destruction of another SAMS-administered hospital in March, as a result of Government of Syria shelling (see: Syria Update 29 March 2021). Assessing who is behind the incident is complicated by the fact that the Syrian Government and Russia have a military presence in neighbouring Tel Refaat. Both parties have ample incentive to destabilise Turkish-controlled population centres, and have done so in the past (see: Syria Update 20 July 2020). Meanwhile, nearby Nubul and Zahra are strongholds of Iran-linked forces, which are also antagonistic toward Turkey. That said, the dominant actor in the area is the YPG, which is effectively a Syrian corollary of the PKK. The Turkish government has asserted that the incident was the work of the YPG and PKK, to which it refers interchangeably, and often in reference to the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF). The Syrian opposition has also pinned blame on the PKK and the YPG’s political wing. Both the SDF and YPG have denied culpability for and condemned the hospital attack.

This land is my land

Afrin looms large in the collective consciousness of Syrian Kurds and Turkey alike. During the reign of Hafez al-Assad, the area was used as a launchpad for PKK attacks against Turkey. More recently, much of the predominantly Kurdish local population of Afrin was displaced as the YPG retreated from the area following Turkey’s Operation Olive Branch in early 2018. Since then, the demographic changes, expropriation, and abuses that have followed Afrin’s capture by Turkish-backed Syrian opposition groups have been a source of gnawing frustration for Syrian Kurds, and the episode is believed to be a motivating factor in car bombs and other attacks likely carried out by PKK or YPG cells in communities under Turkish control in northern Aleppo. Although a causal link is unclear, the Afrin hospital attack has been followed by reported clashes between Turkish-backed armed forces in northeast Syria, at frontlines between the SDF and Turkish-backed armed groups. Meanwhile, on 15 June, the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights reported a car bomb detonation in Kafr Jannah, in rural Afrin, killing at least one person and wounding four.

Meanwhile, in Idleb

The Shifa’a Hospital attack is a sign of rising tensions across northwest Syria. That said, it is not necessarily evidence of a major flare-up in Turkish-Kurdish violence in northern Syria, nor is it a clear signal that the Russian-Turkish ceasefire agreement for neighbouring Idleb is in jeopardy — yet (see: Syria Update 9 March 2020). Since early June, in the wake of Syria’s presidential election, military attacks in northwest Syria have escalated in intensity and widened in geographic scope. In Idleb, coordinated aerial bombardment by Russia and shelling by Government of Syria forces aim to destabilise Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham’s positions near the all-important M4 highway, particularly in Jabal al-Zawiyah (see: Syria Update 14 June 2021). Whether Moscow and Damascus will escalate their attacks and mount a concerted campaign to recapture the areas — as some analysts have suggested — remains to be seen. The large-scale ground preparations that would be needed to sustain such an offensive have yet to be observed. For the time being, civilians near the frontlines can be expected to displace in greater numbers if the shelling continues, but a more sustained effort does not yet appear to be on the cards.

Whole of Syria Review

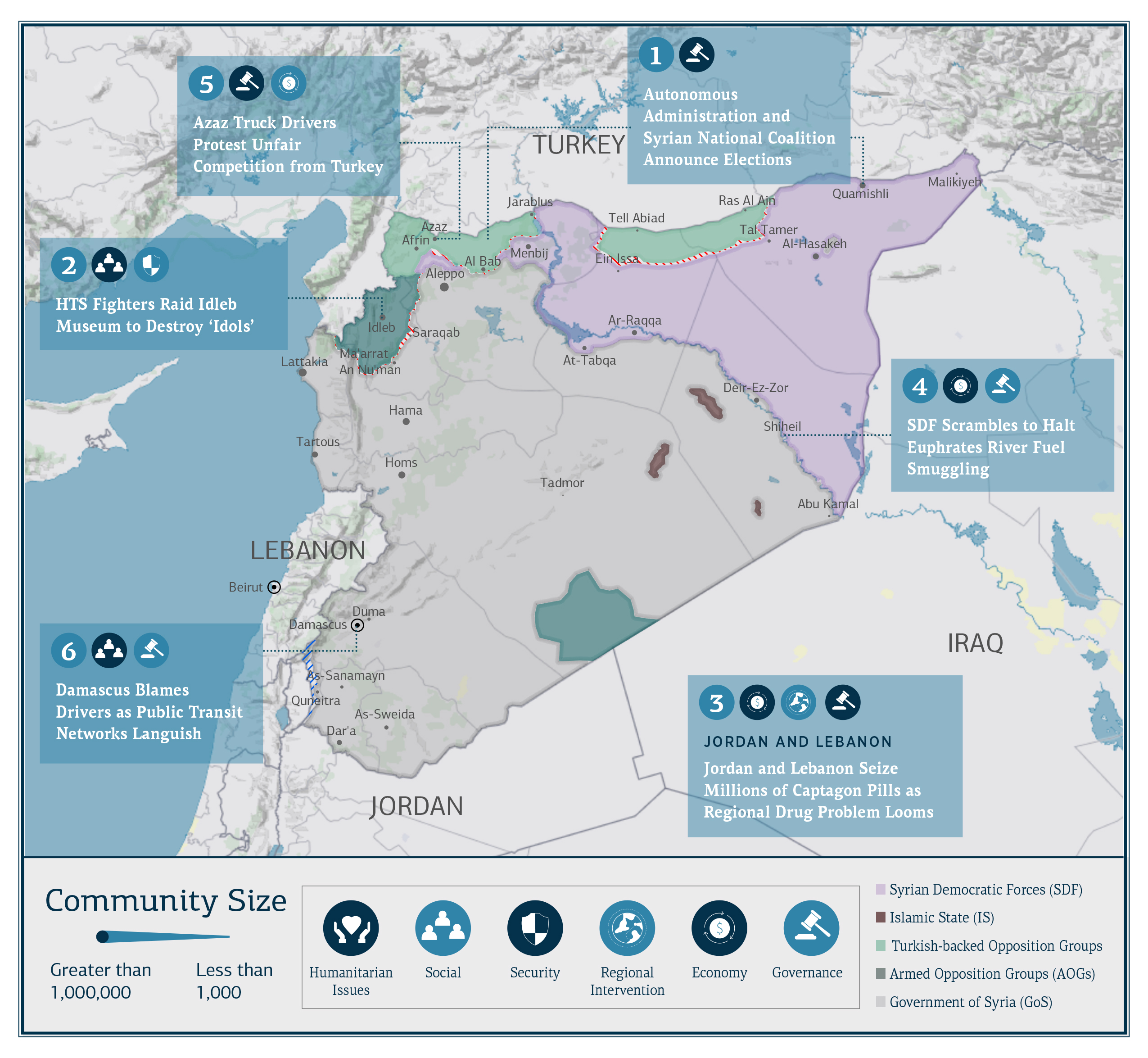

Autonomous Administration and Syrian National Coalition Announce Elections

Quamishli and Northern Rural Aleppo: On 12 June, the Presidency of the Executive Council of the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria announced that it would start preparations to conduct an election later this year. Earlier, on 2 June, Naser al-Hariri, the President of the Syrian National Coalition (Etilaf) announced that it will carry out an election in northwest Syria on 11-12 July, adding that he will not be among the candidates. Al-Hariri said that the election will be run inside Syria, conditions permitting, and called on civil society organisations, media outlets, and country representatives to participate. Whether the voting will be limited to members of the commission is not clear. Previously, local populations have not voted directly.

The ballot and the bullet

The announcements come shortly after the Government of Syria conducted a presidential election that has been widely rejected as a sham (see: Syria Update 31 May 2021). In view of Bashar al-Assad’s dubious re-election, the Autonomous Administration and the Etilaf are likely driven by a desire to showcase functioning democratic systems that are more transparent, inclusive, and representative than their counterparts in Damascus. While the bar has been set low, their own quasi-democratic experiments will face challenges. Both regional governing bodies are more desperate than ever to conduct local elections, not only to delegitimise al-Assad’s rule, but also to recover their own local legitimacy.

In northeast Syria, no election has yet been conducted across all three cantons of the Autonomous Administration’s control. The newly implemented commune system is the keystone of the Autonomous Administration’s political project, and it stipulates the direct election of members of local communes, People’s Municipalities (i.e. local councils), and the Democratic People’s Congress. In the past, various security, logistical, and political challenges have prevented region-wide elections, including a boycott by the Kurdish National Council and the security threats of IS and Turkey. In democratic terms, the Autonomous Administration faces a number of obstacles, including unprecedented popular challenges to its political legitimacy (especially among Arab-majority communities), the dire economic situation, accusations of corruption, deadly crackdowns over forced conscription (see: Syria Update 7 June 2021), and the growing independence of Arab tribes at the local level (see: Northeast Syria Social Tensions and Stability Monitoring: April Update). Holding a local election can hit two birds with one stone: restoring its local legitimacy, and sending the message to the international community that the region remains Syria’s ‘Island of Democracy’. However, it also risks putting a democratic veneer on a system that is fundamentally anti-democratic; if meaningful change and popular representation are elusive, popular pressures may intensify.

In northwest Syria, the relatively sound model of democracy implemented by local councils within opposition-controlled areas came to an end with the establishment of the Salvation Government in Idleb, the Turkish-led military operations in northern Syria, and the Syrian Government’s reclamation of swathes of territory in southern Idleb and elsewhere. Meanwhile, top positions in political opposition bodies such as the Etilaf, the Interim Government, and the High Negotiations Committee (HNC) have been closely held by a small number of figures since the onset of the uprising. Consequently, both the Etilaf and the HNC have faced popular rebuke on social media, much of which has harshly criticised leaders Naser al-Hariri and Anas al-Abdeh for maintaining an iron grip on the two bodies. A grassroots alternative remains highly improbable.

HTS Fighters Raid Idleb Museum to Destroy ‘Idols’

Idleb city, Idleb Governorate: On 11 June, an Uzbek faction of Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) stormed the Idleb National Museum, where they destroyed statues and threatened the staff, according to local media. The Syrian Network for Human Rights condemned the “barbaric action,” specifying that the seven relief carvings had been destroyed because the foreign fighters considered them “idols.” This was not the first time the museum has been targeted. Prior to their withdrawal from Idleb in 2015, Government of Syria forces were accused of looting the museum’s most valuable pieces. Following their withdrawal, Government forces bombed the museum, causing severe damage to the building and to many of the remaining artefacts. The HTS-affiliated Salvation Government reopened the Idleb Museum in August 2018 under the supervision of local antiquities specialists.

Cultural misappropriation

The incident draws attention to the plight of Syria’s cultural heritage, which remains an overlooked casualty of the conflict and will — someday — be an important factor in the country’s post-conflict recovery. Artefacts and historical sites throughout Syria have been destroyed, damaged, and systematically looted and trafficked. The cultural impact of such loss is inestimable, and should be a matter of concern for foreign donors seeking to promote stabilisation, inter-communal reconciliation, and a sense of Syrian national identity. Nearly every community in Syria lays claim to a site of cultural significance, including historic cemeteries, religious shrines, unique artefacts, and museums that were, even in better times, poorly funded. Although such sites are seldom recognised as a priority by aid implementers or donors, they can nonetheless serve as anchors counteracting the destabilising effects of displacement and the destruction of other aspects of local culture. As in the case of the Government forces’ destruction of cemeteries (see: Syria Update 1 March 2021), the loss of cultural heritage may reinforce the sense that communities have been irreparably changed by the conflict. For minority populations in particular, such loss is a physical demonstration that they are no longer welcome. Finding novel ways to repair such damage will be essential to ensuring that Syrians can remain in their changing communities, and that IDPs and refugees have something familiar to return to.

Jordan and Lebanon Seize Millions of Captagon Pills as Regional Drug Problem Looms

Jordan and Lebanon: On 16 June, Jordanian anti-narcotics officers announced the discovery of 300,000 narcotic pills concealed in a produce shipment, according to a Jordanian media report. The drugs were discovered during inspection of a cargo vehicle that entered Jordan from “a neighbouring country,” almost certainly Syria, and were destined for an unnamed country, likely in the Arab Gulf. Meanwhile, on 18 June, authorities in Beirut discovered “millions” of Captagon pills concealed in commercial shipments that Caretaker Interior Minister Mohamed Fahmi said were bound for Saudi Arabia, according to Lebanese media. Just days earlier, Lebanese media reported that 250,000 Captagon tablets were seized in a rare drug bust at Beirut Rafic Hariri International Airport. The shipment was also bound for Saudi Arabia, and was being smuggled by Syrian and Lebanese traffickers.

Riding high on its own supply

Harmful blowback from the Middle Eastern Captagon trade is mounting. It is increasingly apparent that the drug trade poses a risk to legitimate economic activity, creating yet another burden for struggling producers, exporters, and transit workers in Syria and its neighbouring states, including Lebanon — which now faces export restrictions in Saudi Arabia. Although regional counter-narcotics forces are increasingly on alert, they can do little more than mitigate downstream consequences.

To a large extent, the flourishing regional drug trade is a direct product of the Syria crisis (see: The Syrian Economy at War: Captagon, Hashish, and the Syrian Narco-State); with few economic resources at its disposal, the Assad regime and its foreign backers, including Hezbollah and regional macro-entrepreneurs, have embraced the drug trade as a means of illicit finance. While Syria is at the centre of the regional Captagon trade, growing economic desperation has increased the incentive for Hezbollah and other actors in Lebanon to fill their own coffers through narco-financing, too. Such is the law of unintended consequences. In the long term, policy-makers must grapple with the fact that the rise of such narco-enterprises is among the consequences of a strategy to financially isolate the Assad regime and its foreign backers. How the West will shore up neighbouring states that bear the costs of a wave of narcotics is less clear, but prosocial approaches, including support for drug treatment, will be important steps to ensure desperate populations are not forced to endure further harms as blowback spreads.

Meanwhile, there is no end in sight for the regional Captagon trade. Syrian state media have touted the recent appointment of a new Government of Syria representative to the UN Office on Drugs and Crime as a step toward greater counter-narcotics cooperation. This is a hollow gesture; real progress on Syria’s drug problem will come only when the regime no longer seeks to exploit the drug trade as a financial and political imperative.

SDF Scrambles to Halt Euphrates River Fuel Smuggling

Shiheil, Deir-ez-Zor Governorate: On 13 June, local media reported that smugglers operating alongside the Euphrates River in southern Deir-ez-Zor are increasingly resorting to new smuggling tactics to transport oil across the river to evade detection by the SDF, as it ramps up its anti-smuggling operations. One such method, nashalat, uses a pump hidden in a house adjacent to the river to pump oil via a pipeline to the other side. According to the report, there are around 35 pumps located along the river in rural Deir-ez-Zor, each one pumping around 300 barrels per day from the SDF-controlled side to Government of Syria-controlled areas. On both banks, security officials affiliated with the SDF, Government security forces, and Iranian militia groups facilitate and sponsor this process. Meanwhile, the Syrian Observatory for Human rights and local sources report that the SDF has been cracking down on smuggling routes for several months in east rural Deir-ez-Zor, especially Shiheil and its surrounding towns. Over the past three months, the SDF has carried out dozens of raids, detaining dozens of people, confiscating goods, and destroying boats suspected to be carrying smuggled wares (see: Northeast Syria Social Tensions and Stability Monitoring: April Update).

More than smuggling routes

The politics of fuel is a main pillar of the SDF’s governance and political agenda. Fuel trade with Damascus is an important bargaining chip for the Autonomous Administration; although daily fuel shipments run by the GoS-linked Qaterji family have officially resumed after several suspensions due to security issues and pressure on the Autonomous Administration from the US, they are insufficient to meet demand within GoS-controlled areas. Smuggling routes along the Euphrates River help offset the shortage, and offer the communities that control them an opportunity to gain considerable economic and political influence. Such was the case if Shiheil — the community’s importance as a smuggling hub and its success in securing alternate sources of support have allowed it to assert independence from controlling actors such as IS and the SDF.

However, Shiheil’s smuggling routes carry not only fuel, but also ideas (and guns). The Government of Syria has reportedly been capitalising on rising anti-SDF sentiment in northeast Syria to conduct outreach to local notables and tribal entities in Shiheil. The Government aims to deliver weapons through smuggling routes in order to increase the capacity of local cells resistant to the SDF and the US-led International Coalition. The SDF is more determined than ever before to put an end to smuggling activities in Shiheil. Squelching these activities would advance its overarching objectives, including by undermining the town’s economic independence, reducing the ‘unofficial’ fuel supply to Government-controlled areas, and cutting ties between local actors in Shiheil and the Government of Syria.

Azaz Truck Drivers Protest Unfair Competition from Turkey

Azaz, Aleppo Governorate: On 12 June, dozens of Syrian truck drivers organised a sit-in in Azaz to protest the decision by the Bab al-Salameh crossing administration in March 2019 that allows Turkish trucks to deliver goods inside Syria, undercutting local drivers. Previously (between 2011 and 2019), Turkish trucks were required to unload goods at the Bab al-Salameh crossing so that Syrian trucks could transport them to Syrian markets. In an interview with local media, one driver stated that more than 5,000 Syrian truckers have been affected by the crossing administration’s decision. Abdelhakim al-Masri, the Interim Government’s Minister of Finance, said that the law does not privilege any particular group; al-Masri suggested that traders prefer to hire Turkish drivers due to favourable logistical and financial bids.

Northern Syria’s other border battle

The trucking sector is a bellwether of the mixed impact of Turkish economic intervention in northern Syria. As with other sectors, the procedural changes at Bab al-Salameh have been beneficial to some and damaging to others. Shipping goods on a single truck from the point of origin in Turkey to a destination in Syria is clearly more cost-effective, and thus a preferred option for the majority of traders. Reduced market prices benefit consumers and potentially increase the purchasing power of cash assistance and other forms of market-based donor support. However, the changes also undercut the competitiveness of Syrian labour and enterprise; hundreds of truck drivers and freight workers risk losing their main source of income. In general, areas under Turkish influence, in particular Euphrates Shield areas, have witnessed remarkable improvements in service provision, availability of basic goods, and price stability. Obviously, for Turkey, the integration of new markets for the domestic produce is potentially enormous: Northern Syria’s population is roughly 5 percent of Turkey’s, making the region an attractive and sizable outlet for commercial goods. With Turkish influence only deepening, aid actors must consider how to support Syrian enterprises and workers in a way that capitalises on Ankara’s regional strategy without undercutting Syrians’ long-term domestic and regional needs.

Damascus Blames Drivers as Public Transit Networks Languish

Damascus: On 13 June, Amer Khalaf, a member of the Executive Office of Transport in Rural Damascus Governorate, declared that more than 40 percent of Syria’s public transit network — mainly taxis and microbuses — had been rendered inoperative. Khalaf added that the current transportation crisis in Government-held areas is not a result of chronic fuel shortages, but rather the behaviour of drivers, whom he accused of selling fuel allowances and opting for private-sector work.

The buck stops there

Syria’s public transport predicament is part of a series of ongoing crises that span Government-held areas. Khalaf’s statements follow months of rising fuel prices and recurrent shortages in early 2021. Supply-side factors, not transit drivers’ alleged unwillingness to work, have hamstrung the transportation sector. Buses and taxis have grown in importance in the last decade due to the rising cost of private transportation, the difficulty of sourcing new vehicles and parts, and the soaring cost of fuel as subsidies are gradually scaled back. Donors should be cognisant of transport-related issues, which are easily overlooked, but can play a spoiler role in aid activities that rely on beneficiary mobility.

Open-Source Annex

Key Readings

The Open Source Annex highlights key media reports, research, and primary documents that are not examined in the Syria Update. For a continuously updated collection of such records, searchable by geography, theme, and conflict actor, and curated to meet the needs of decision-makers, please see COAR’s comprehensive online search platform, Alexandrina, at the link below..

Note: These records are solely the responsibility of their creators. COAR does not necessarily endorse — or confirm — the viewpoints expressed by these sources.

New Evidence Links a Far-Right French NGO to War Crimes in Syria

What Does It Say? New evidence has surfaced that SOS Chrétiens d’Orient, a French NGO linked to France’s far-right political and military elite, secretly financed a sanctioned pro-Assad militia which killed and tortured Syrians. The piece indicates that there is now enough evidence to take the case to French court.

Reading Between The Lines: The aid provided by this French group is just one of many instances of foreign financial assistance to unsavoury actors during the Syrian conflict, and it is evidence of the pitfalls that await donors who operate without sufficient conflict-sensitivity analysis.

The Turkish Lira in Northern Syria: A Year of Circulation

What Does It Say? The report lays out the impacts of growing use of the Turkish lira in northern Syria following the crash of the Syrian pound over the last year, including more stable prices in local markets and deeper integration of the region into the Turkish economy.

Reading Between The Lines: Prices of basic goods such as bread, vegetables, and meat have been more stable than in Government of Syria-controlled areas; fuel is the exception. Aid actors can take note of these impacts to steer their market-based activities.

How the Small Town of Sarmada Became Syria’s Gateway to the World

What Does It Say? In parallel with Aleppo’s decline as Syria’s economic capital, Sarmada has emerged as a powerhouse due to its proximity to the Turkish border, and has become a major hub for commercial activities and humanitarian supply chains.

Reading Between The Lines: Sarmada’s economic significance has led to growing competition for influence over the town, although neither Turkey nor HTS has firm control over the area. This battle for control could lead to the area’s destabilisation, threatening humanitarian access and taking a toll on Idleb’s economy.

What Does It Say? Suspending cross-border aid delivery through Ya’robiyah has had a severe impact on humanitarian conditions in northeast Syria, and has made the region reliant on Damascus to authorise aid shipments. The situation in the northeast indicates that cross-line aid delivery is not a substitute for cross-border aid, and the population will clearly suffer if the cross-border mechanism is not renewed.

Reading Between The Lines: In the one and a half years since the crossing closed, only one UN road convoy has made it from Damascus to the northeast. Meanwhile, cross-line aid delivery in the northwest has been subject to various security, political, and operational restrictions.

The Syrian Government is Seizing Large Swathes of IDPs Lands in Hama and Idlib Suburbs

What Does It Say? The Syrian Government recently seized agricultural lands in parts of Hama and Idleb governorates and put them up for public auction.

Reading Between The Lines: These seizures turned hundreds of farmers into IDPs and deprived them of their livelihoods, forcing more Syrians to rely on humanitarian assistance. For Damascus, that is an ideal outcome: displacing such populations while claiming their productive agricultural properties gives the Government of Syria greater access to a land without a people, which it can exploit economically.

Investment Projects in Idleb, Challenges and Opportunities of Success

What Does It Say? A variety of small- and medium-scale investment projects, including in the trade and manufacturing sectors, have been launched in Idleb. However, expanding existing projects or opening a new enterprise presents deep challenges because of the lack of financial institutions and legal frameworks required to enable new investments.

Reading Between The Lines: Even if the investment environment improves, it is hard to imagine foreign capital from anywhere outside of Turkey flowing into Idleb so long as HTS is designated as a terrorist group.

NGOs Employees Morally and Financially Blackmailed in Syria’s Raqqa

What Does It Say? Locals are forced to endure all manner of extortion and blackmail schemes in order to secure jobs with NGOs operating in Ar-Raqqa. The Autonomous Administration’s Social Affairs and Labour Committee (SALC) seems unwilling or unable to help.

Reading Between The Lines: With the country’s ongoing economic deterioration and NGO work offering a very attractive livelihood by local standards, predatory hiring practices are unfortunately not uncommon.