Executive Summary

A comprehensive study of LGBTQ+ Syria has yet to be written. Although LGBTQ+ issues have come to the fore at various stages of the ongoing conflict, gender and sexual minorities in Syria have more often than not been ignored and actively marginalised. As a result, the impact of conflict-related violence on LGBTQ+ persons and the resulting needs of LGBTQ+ beneficiaries have been kept out of view by what one advocate has described as “walls of silence”.[1]Ayman Menem, “Voices breaking the silence: Fighting for personal freedoms and LGBTIQ rights in Syria,” Syria Untold (2020): https://syriauntold.com/2020/11/03/voices-breaking-the-silence/. This report is a preliminary attempt to rectify this oversight.[2]COAR is grateful for the input of LGBTQ+ interviewees, legal experts and advocates, NGO workers, and others who have contributed information for this report. COAR also wishes to extend special … Continue reading Among the most pervasive misconceptions this research seeks to correct is the widely held belief that LGBTQ+ issues are somehow of marginal importance in Syria. As explored below, the recognition of LGBTQ+ persons and their specific experiences of conflict is imperative not only for reasons of equality and social justice — the failure to bring these issues to attention also impedes effective donor-supported aid programming, political advocacy, and accountability.

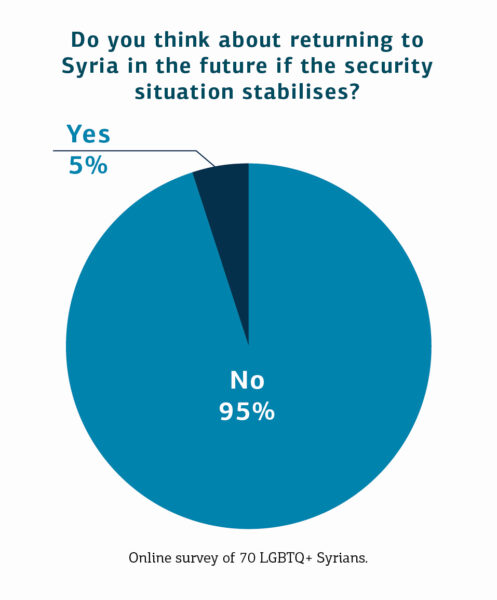

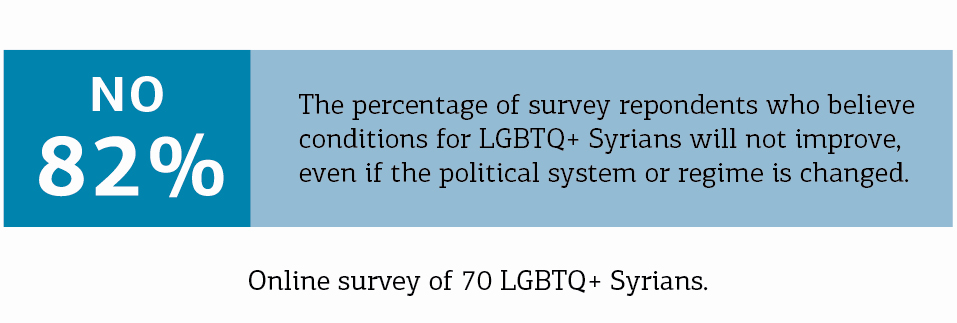

This paper provides a summary overview of LGBTQ+ issues in wartime Syria. It is based on an extensive review of relevant academic and sectoral literature, key-informant interviews (KIIs) with aid practitioners and LGBTQ+ Syrians, and the results of an online survey of 70 LGBTQ+ Syrians.[3]Sample: 70 LGBTQ+ Syrians, aged 22-36 years old, residing in Turkey, Europe, and Canada, including 50 homosexual males, 18 transgender women, 2 homosexual women. The survey was conducted in Arabic … Continue reading Treating the conflict as a critical branch point in Syria’s recent social history, the report details LGBTQ+ experiences in various zones of control and in main countries of asylum. It then documents the myriad challenges that face LGBTQ+ Syrians inside the country and abroad, including healthcare disparities, legal discrimination, social prejudice, and the unpreparedness of aid workers to meet resulting needs. Finally, it concludes with an extensive discussion of practical recommendations for donor-funded aid activities that can begin to address the needs of LGBTQ+ Syrians. It is impossible to condense the full diversity of Syrian LGBTQ+ experiences into a single report, let alone a report of this length. Ultimately, it is our hope that this research can serve as a conversation starter concerning a dimension of Syrian life that is seldom acknowledged and poorly understood.[4]Kyle Knight, “LGBT People in Emergencies — Risks and Service Gaps,” Human Rights Watch (20 May 2016): https://www.hrw.org/news/2016/05/20/lgbt-people-emergencies-risks-and-service-gaps. Only by beginning with a recognition of past and present blind spots can institutional donors and implementers alike begin to address issues of importance to LGBTQ+ Syrians, whose marginalisation in aid activities exacerbates conflict-related traumas and systemic needs.

LGBTQ+ Syrians: An Overlooked Minority Group

No reliable figures concerning the number of LGBTQ+ Syrians exist. This data gap is more difficult to overcome because social, religious, and historical factors can militate against self-identification and disclosure of LGBTQ+ identity. In the absence of reliable data and without a strong history of organised pro-LGBTQ+ political mobilisation in Syria, the assumption that LGBTQ+ individuals are a marginal subgroup has become a default position for many Syrians. That assumption has, to some extent, been adopted by practitioners working within the Syria crisis response, including analysts, donors, and aid implementers. In response to this failing, reference can be made to the work of the Humanitarian Advisory Group and Heartland Alliance International, which are among the few actors to have systematically considered LGBTQ+ issues in aid work, respectively assessing general humanitarian contexts and the case of LGBTQ+ Syrians in Lebanon. They advise that 5 percent should serve as a “conservative rule of thumb” for the prevalence of sexual and gender minorities among beneficiary populations.[5]Heartland Alliance grounds its own recommendation in the work of the Humanitarian Advisory Group. “Taking Sexual and gender minorities out of the too-hard basket,” Humanitarian Advisory Group … Continue reading

Applying this rule of thumb in the case of Syria suggests that aid actors should plan to accommodate roughly 1 million LGBTQ+ persons across all zones of control in the country, and more than a quarter-million such persons in Turkey, Lebanon, and Jordan. Interestingly, local sources and KIIs interviewed for this report almost universally dispute the validity of such a figure. They point to factors such as the fluidity of identity, or contend that Syria’s history, culture, or traditions mean that prevalence figures conceived in Europe or Asia, for instance, do not fit easily into the local context.[6]Population-level estimates of LGTBQ+ populations in other countries range from 1.5 percent to more than 10 percent. Mona Chalabi, “Gay Britain: What do the statistics say?” The Guardian (2013): … Continue reading In truth, it is next to impossible to test the accuracy of such an estimate under current conditions in Syria, but arriving at a conclusive numeric figure is not necessary to determine that aid actors have consistently failed to meet the needs of LGBTQ+ Syrians. Bringing current industry standards to bear in Syria demonstrates unambiguously that the failure to incorporate LGBTQ+ perspectives throughout contextual analysis and aid delivery has marginalised and ignored the needs of a considerable population group. Indeed, LGBTQ+ Syrians may be as numerous as ethnic or religious minority populations that are far more readily recognised within mainstream analysis and aid paradigms. That being said, LGBTQ+ status should be approached as a cross-cutting identifier that overlaps with other aspects of identity (e.g. gender, sect, ethnicity, tribe, political ideology) and serves as an important factor that shapes the experiences and needs of individuals and groups.

LGBTQ+ Experiences after 2011

The ongoing conflict has affected the visibility, collective identity, and political agenda pursued by communities of LGBTQ+ Syrians, particularly those abroad. While LGBTQ+ issues were not a mainstay concern motivating the Syrian popular uprising in 2011, there was nonetheless cautious optimism that a pro-democracy movement predicated on the expansion of individual and collective rights could improve conditions for LGBTQ+ Syrians. Following the onset of the uprising in March 2011, some activists explicitly called for the inclusion of LGBTQ+ rights in the broad palette of popular demands. In some sense, this was an inevitable result of the heavy involvement of LGBTQ+ individuals in Syria’s revolutionary political and social movements.[7]Ayman Menem, “Voices breaking the silence: Fighting for personal freedoms and LGBTIQ rights in Syria,” Syria Untold (2020): https://syriauntold.com/2020/11/03/voices-breaking-the-silence/. However, others in the LGBTQ+ movement downplayed the pro-LGBTQ+ discourse as being unrealistic in the face of a political and armed struggle against Syria’s authoritarian military establishment. To some extent, this view was validated as the Syrian uprising became increasingly militarised and the LGBTQ+ community became divided between Assad regime loyalists and the opposition.[8] Ibid.

LGBTQ+ Syrians have endured the conflict by navigating waves of violence and changing social dynamics brought on by the competing ideologies of armed actors, including some groups that were overtly hostile to LGBTQ+ individuals. The conditions that have determined social life, legal status, health care access, and other important matters for LGBTQ+ Syrians since 2011 have largely been contingent on the governing authorities, whether inside Syria or abroad. Currently, Syria is divided into three regions presided over by the Government of Syria (in central, southern, and coastal Syria), the Autonomous Administration (in the country’s northeast), and various armed opposition groups (in the northwest). Outside Syria, the main countries of interest are Turkey, Lebanon, and Jordan.[9]It should be noted that although Iraq is a border state hosting Syrian refugees, a detailed account of LGBTQ+ events there has been excluded from this report because of the comparatively small number … Continue reading

Government of Syria

Syria’s legal code and repressive political system criminalise homosexuality and outlaw most forms of LGBTQ+ activism and mobilisation (see: the section on Challenges below.) Sexual and gender identity have been distinct vulnerability criteria in Government areas, as the devolution of the rule of law has increased the power of criminal gangs and opportunistic criminal actors, leading LGBTQ+ individuals to report cases of extortion, blackmail, and kidnapping for ransom.[10]Hannah Lucinda Smith, “How Jihadists are blackmailing, torturing, and killing gay Syrians,” Vice.com (2013): https://www.vice.com/en/article/gq8b4x/gay-syrians-are-being-blackmailed-by-jihadists. LGBTQ+ identity also amplifies the risk for those who are detained or arrested by state security forces for any reason. Given that the risk of arbitrary detention is omni-present in Government-held areas, LGBTQ+ status is therefore a pronounced factor affecting personal safety and protection status. Government of Syria detention centers and prisons have routinely been identified as sites of torture and abuse, including sexual and gender-based violence and humiliation for those suspected of LGBTQ+ identity.[11]“Discrimination and Violence against Individuals Based on Their Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity,” OHCHR, UN Doc. A/HRC/29/23, 4 May 2015; Graeme Reid, “The Double Threat for Gay Men in … Continue reading The documented abuses include forced nudity, rape, and anal or vaginal “examinations” carried out by Syrian Government forces (and by armed groups), often as a tool of coercion or punishment in detention facilities.[12]Ibid. In case of arrest, contact lists, text messages, photos and videos, and other digital information can increase the risk if authorities discover or believe that a detainee is LGBTQ+. Perhaps the most visible security risk pertains to transgender persons. Acute danger arises when individuals pass through army and security service checkpoints, where they are forced to provide ID cards that often do not match their current physical appearance, which frequently leads to humiliation, verbal abuse, assault, and arbitrary arrest.[13]“They Treated Us in Monstrous Ways: Sexual Violence Against Men, Boys, and Transgender Women in the Syrian Conflict” Human Rights Watch (2020): … Continue reading

An additional consideration for LGBTQ+ individuals in Government of Syria areas is compulsory and reserve military service in the Syrian Arab Army. For some individuals, service has lasted as long as eight years due to troop shortages, defections, battle losses, and the fluctuating needs of military campaigns.[14]“Syria Military service Country of Origin Information Report” EASO (2021): https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/2021_04_EASO_COI_Report_Military_Service.pdf. Homosexual men, in particular, have faced additional pressure to leave the country due to the individualised risks that accompany forced military service.[15]“They Treated Us in Monstrous Ways: Sexual Violence Against Men, Boys, and Transgender Women in the Syrian Conflict” Human Rights Watch (2020): … Continue reading

Armed Opposition Groups

The diversity of armed opposition groups in Syria impedes any attempt to summarise the experiences of LGBTQ+ persons in opposition-held areas in detail. At times, prominent Free Syrian Army figures expressed neutral or openly supportive views of LGBTQ+ rights. However, even members of the secular opposition acknowledged social barriers to the acceptance of LGBTQ+ Syrians, and some expressed a personal tolerance for violence against LGBTQ+ people, including stoning.[16]One Free Syrian Army fighter was quoted as saying: If someone said homosexuals should be stoned to death as in Iran and Saudi Arabia, I would not object.” See: Reese Erlich, “Gays join the Syrian … Continue reading Writ large, throughout the conflict, territories held by armed insurgent groups have arguably been the most overtly hostile environments for LGBTQ+ Syrians, particularly areas held by violent extremists.[17]“Conflict-Related Sexual Violence,” Reports of the UN Secretary-General, UN Doc. S/2015/203, 23 March 2015, and UN Doc. S/2016/361, 20 April 2016; Michelle Nichols, “Gay Men Tell UN Security … Continue reading Although sweeping claims should be approached cautiously, foreign-born armed group fighters were generally more zealous and punitive in LGBTQ+ matters than Syrian combatants in the same groups.[18]Hannah Lucinda Smith, “How Jihadists are blackmailing, torturing, and killing gay Syrians,” Vice.com (2013): https://www.vice.com/en/article/gq8b4x/gay-syrians-are-being-blackmailed-by-jihadists. That being said, the frequent changes in controlling actor and armed group mergers and fragmentation have made it difficult to identify actors responsible for violations against LGBTQ+ individuals, thus hampering accountability efforts. In spite of the risks that often manifest as open hostility toward LGBTQ+ persons, opposition areas have continued to attract LGBTQ+ males in particular, given that these areas are seen as a safe refuge from Syrian Government security services, arrest, or military service. In addition, they offer a pathway to asylum in Turkey or Europe (on an open basis before January 2016 and via smuggling routes following the tightening of restrictions thereafter).

Islamic StateDuring its time as a major territorial actor, IS carried out the most public persecution of LGBTQ+ Syrians of the entire conflict. In IS-held areas of Syria and Iraq, those accused of “criminal” sexual conduct — actions the group described as sodomy, adultery, or “indecent behaviour” — were stoned or hurled from the rooftops of high-rise buildings as a form of public execution. Often, the group theatrically choreographed and recorded such events for use in online propaganda videos.[19]“Timeline of Publicized Executions for ‘Indecent Behavior’ by Islamic State Militias,” OutRight Action International (2016): www.outrightinternational.org/dontturnaway/timeline. IS often carried out its punishments on the basis of suspicion or hearsay.[20]A conviction for such “crimes” requires four male witnesses or voluntary confession, under traditional Islamic jurisprudence. Unverified anecdotal reports indicate that such conditions likely drove some gay men to join IS, whether as fighters or administrative functionaries, as a form of preemptive protection.[21]As reported by numerous key informants; Hannah Lucinda Smith, “How Jihadists are blackmailing, torturing, and killing gay Syrians,” Vice.com (2013): … Continue reading By linking homosexuality with the West, IS cast suspicion on LGBTQ+ Syrians as a whole and sought to cut them off from their communities. In addition to framing its oppressive measures as a necessity for protecting virtue and preventing vice, IS presented the executions as retribution for the Crusades launched by revanchist Christian European rulers in the medieval period. Implicitly, the group’s approach cast LGBTQ+ Syrians as traitors and collaborators promoting an alien Western agenda. The accounts of LGBTQ+ Syrians indicate that in response to these pressures, neighbours, friends, confidants, partners, former schoolmates, and even family members “sold them out” to various armed groups, including IS.[22]Dan McDougall, “It can’t get any worse than being gay in Syria today,” Sydney Morning Herald (2015): … Continue reading Such denunciations often ended in execution. IS’s willingness to wield violence publicly also had the perverse effect of making the abuses against LGBTQ+ individuals in areas controlled by the other parties appear trivial and therefore acceptable. Such abuses — and their tacit acceptance — have impeded community reconciliation and LGBTQ+ recognition, even after IS’s demise. |

Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria

Northeast Syria is the region of the country that is ostensibly most open to the recognition of LGBTQ+ rights, although in reality these are often truncated. In theory, the Autonomous Administration’s Charter of the Social Contract, the functional equivalent of a constitution, offers a rights-based model that promotes political participation, women’s rights, and civil marriage.[23]PYD Rojava, Contract of the Social Charter: . It also provides nominal guarantees of the rights of LGBTQ+ individuals. In practice, however, its promises have not been fulfilled. Article 21 of the Charter guarantees human rights as per international agreements, while Article 22 confirms the Autonomous Administration’s adoption of the International Bill of Human Rights,[24]“Fact Sheet No. 2 (Rev. 1), The International Bill of Human Rights,” United Nations (1996): https://www.ohchr.org/documents/publications/factsheet2rev.1en.pdf. the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights,[25]“International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights,” United Nations (1976): https://www.ohchr.org/en/professionalinterest/pages/cescr.aspx. and other relevant agreements, which are considered integral to the Autonomous Administration’s own legal frameworks. However, LGBTQ+ rights have not been substantively addressed, an oversight that officials have obfuscated by focusing on the prioritisation of other rights. The experiences of northeast Syria demonstrate that LGBTQ+ rights are not anathema to Syrians, yet they also furnish an important warning on the disconnect between legal progress and de facto social realities. Although the Autonomous Administration has adopted human rights charters and de-criminalised homosexuality, homosexual acts continue to be treated as an offence. Homosexuals have at times been arrested on the pretext of alleged public interest (i.e., on the basis of social customs and traditions).

Of note, IS’s deliberate brutality prompted arguably the most visible pro-LGBTQ+ incident of the conflict in Syria: the supposed formation of an LGBTQ+ armed battalion in Ar-Raqqa city in July 2017, fighting alongside the SDF against IS.[26]IRPGF, Twitter (24 July 2017): https://twitter.com/IRPGF/status/889445690656608256?s=20. The group’s social media debut was an affirming gesture of decisive action when many LGBTQ+ Syrians expressed a sense of abandonment by the global LGBTQ+ community. However, its association with the U.S.-led International Coalition has been criticised for reinforcing the image that LGBTQ+ issues are inherently linked to a Western interventionist agenda.[27]Razan Ghazzawi, “Decolonising Syria’s so-called ‘queer liberation’,” Al-Jazeera (2017): https://www.aljazeera.com/opinions/2017/8/5/decolonising-syrias-so-called-queer-liberation; Ayman … Continue reading SDF commander Mustafa Bali subsequently downplayed the apparent PR stunt: “while emphasizing our deep respect for human rights, including the rights of homosexuals, [we] deny the formation of such a battalion within the framework of our forces.[28]Hisham Arafat, “US-backed forces deny having LGBT military unit in Syria,” Kurdistan 24 (2017): https://www.kurdistan24.net/en/story/12139-US-backed-forces-deny-having-LGBT-military-unit-in-Syria. ” Above all, the initiative focused attention on the apparent disconnect between LGBTQ+ persons in Syria and abroad. Indeed, 95 percent of LGBTQ+ Syrians surveyed by COAR said they do not feel a sense of solidarity from the LGBTQ+ global community despite the ravages of the conflict.

The Syrian LGBTQ+ Community in Countries of Asylum

According to UNHCR, more than 5.6 million Syrians are formally registered as refugees. There are no reliable figures on how many LGBTQ+ Syrians have left the country, although using the 5 percent baseline as a guide, implementers may expect as many as 260,000 LGBTQ+ Syrians are registered as refugees in neighbouring major host countries alone. While many LGBTQ+ Syrians view asylum abroad as the most durable solution to their protection concerns, non-normative identities can create friction in host countries, particularly those in the Middle East, owing to religious and social stigma.

Turkey

Turkey is widely considered to be the country most open to sexual minorities in the greater Middle East region, and it is host to the largest number of Syrian refugees in the world. LGBTQ+ people in Turkey enjoy relative freedom, especially in more cosmopolitan cities such as Istanbul. However, some of these freedoms have been rolled back in recent years.

Following the influx of Syrian refugees into Turkey in the early years of the conflict, the country came to host what was arguably the first organised Syrian LGBTQ+ movements and associations, launched in large part by gay men in Istanbul (see inset: Milestones of the Syrian LGBTQ+ Movement in Turkey). Several important factors have facilitated mobilisation within the Syrian LGBTQ+ community in Turkey: Homosexuality has long been decriminalised in the country, although social stigma persists, especially in more conservative, outlying areas.[29]In 1858, Sultan Abdul Majid I decriminalised homosexuality, thus granting homosexual adults the right to engage in sexual activity without threat of legal punishment.Indeed, Turkey has a long record of receiving and granting protection status to sexual minorities from places such as Iraq and Iran; the country has increasingly acted as a crossroads for migration from Asia and Africa to Europe, which — in recent years — has coincided with a rise in the numbers of LGBTQ+ asylum seekers. Moreover, trans people are able to participate in public life relatively openly, particularly in Istanbul.[30]Erin Cunningham, “In Turkey, it’s not a crime to be gay. But LGBT activists see a rising threat.” The Washington Post … Continue reading In addition to these factors, the reception of LGBTQ+ Syrian refugees was arguably eased by long-running efforts by the Turkish government to gain entry to the European Union, which provided incentive for the recognition of LGBTQ+ rights through legal reforms consistent with EU baselines.[31]“Turkey and Montenegro: LGBT rights part of EU accession conditions,” European Parliament LGBTQI Intergroup (2011): … Continue reading

Contingent factors have also nurtured the Syrian LGBTQ+ community in Turkey, with important lessons that may inform best practices for resettlement in other contexts. Among these factors is the LGBTQ+ community’s concentration in a single metropolitan area, Istanbul, which has facilitated organising and collective action. This contrasts with the refugee experience in Europe or North America, where geographic dispersal — seen as an imperative for integration — has unintentionally impeded mobilisation on issues of LGBTQ+ solidarity. Additionally, the nature of the temporary protection system in Turkey has arguably furnished greater space for organising. With less focus on language education and limited support for integration, Turkey has, albeit inadvertently, left LGBTQ+ refugees and asylum seekers greater bandwidth to organise. Finally, local sources indicate that Turkish civil society organisations with recent experience in social advocacy and organising have also provided critical support to the emerging Syrian LGBTQ+ community in the country.

Image courtesy of Bradley Secker.

Perhaps the cultural high-water mark of the Syrian LGBTQ+ community’s overt public presence in Turkey came in 2014, with the Istanbul Gay Pride Parade. The freedoms on public display have since been rolled back, to some extent. Vague concern over security and public order has been cited in the decision to ban Pride gatherings in Istanbul, while “social sensitivities” and similar justifications have been referenced in bans on public events focused on LGBTQ+ issues in Ankara and elsewhere.[32]Emel Altay, “Syrian LGBTI refugees struggle in Turkey,” Journo (2018): https://journo.com.tr/syrian-lgbti-refugees-struggle-in-turkey; Turkey: End Ankara Ban on LGBTI Events, Human Rights Watch … Continue reading Many view this reversal as a result of the changing socio-political climate in Turkey, which coincided with the breakdown of its bid for EU membership — though additional factors are also relevant.[33]“Freedom in the World, 2021: Turkey,” Freedom House, https://freedomhouse.org/country/turkey/freedom-world/2021. Host-refugee relations for Syrians in Turkey have worsened as fiscal instability and the deterioration of the Turkish economy have brought Syrians into pitched economic competition with Turks. Media and popular incitement against Syrians in the country have followed. Paradoxically, the lax integration regime that has facilitated organising by LGBTQ+ Syrians in Turkey has undermined security and protection for those same individuals — who benefit from fewer guarantees of personal freedom and less robust support frameworks to facilitate social acceptance, particularly when set against the protections offered in Western states. Consequently, many Syrians view their status in Turkey as uncertain, contingent on shifting political fortunes that are outside their control. This is exacerbated by the fact that LGBTQ+ Syrians in Turkey, as elsewhere, encounter prejudice from other refugees as well as host communities.

Milestones of the Syrian LGBTQ+ Movement in TurkeyMawaleh Magazine: In 2013, Syrian LGBTQ+ activists living in Turkey began to publish Mawaleh magazine, the first internet periodical focused on Syrian LGBTQ+ issues. The inaugural editorial stated: “This magazine addresses us first, discussing our problems and proposing solutions. Perhaps one day we will reach full awareness about our existence as homosexuals and about the rights we are entitled to enjoy as any member of society. … Mawaleh is a magazine about homosexuality in Syria. Far from political tendencies, its first and last concern is the rights of homosexuals in Syria.” The magazine was published until 2016. LGBT Radio: “We are homosexuals; not people hankering for fun and sex. We do our duty to serve our society. We also want to claim our right to respect, dignity, and protection — I am gay and I want to live with respect and dignity – I am just like you.” This concept underwrote LGBT Radio, a station that was meant to launch on 17 May (the International Day Against Homophobia, Transphobia, and Biphobia) 2013, as the first Arab radio station addressing gay issues. Its programming was to concentrate on legal and health education. However, although programming and training concepts were mooted, the initiative never went live as a broadcast radio station, according to local sources interviewed for this report. Shai w Haki (Tea and Talk): Shai w Haki was the first organised Syrian LGBTQ+ forum in Istanbul, starting in February 2015 as a weekly community meeting revolving around LGBTQ+ issues and the exchange of advice on living in Turkey. With the help of volunteers, it developed from a discussion forum into a service-oriented support network for the Syrian LGBTQ+ community in Istanbul. It ultimately began to provide services and language courses in English and Turkish. The forum’s work is ongoing, with over 700 participants. However, many community members have been resettled elsewhere by UNHCR. Mr Gay Syria: The Mr Gay Syria contest was first organised by volunteers in 2016. It drew the attention of refugee-receiving countries to the suffering of LGBTQ+ refugees and the need to classify them as having “an urgent need” for resettlement. Despite sparking controversy, the contest was a milestone in the history of the LGBTQ+ movement in the region as a whole. It was also the subject of a documentary film that won a number of international awards.[34]Ayse Toprak, “Mr Gay Syria 2017,” Coin Film, (2021): https://www.coin-film.de/en/filme/mr-gay-syria/ |

Lebanon

Lebanon is often viewed as the most permissive Arab state in terms of gender and sexual identity, although this toleration is limited in practice, particularly for Syrians. The country has no law specifically protecting LGBTQ+ individuals from targeted violence; on the contrary, Law No. 534 criminalises sexual behaviour that “contradicts the laws of nature”, implicitly singling out LGBTQ+ relations.[35]“Laws of Nature,” The Economist (2014): https://www.economist.com/pomegranate/2014/03/14/laws-of-nature Although this law is worrying in its potential use against Lebanese citizens, local sources note that it has often been deployed punitively in the course of police actions against Syrian refugees, particularly trans women and sex workers. The law is emblematic of the twin vulnerability experienced by LGBTQ+ Syrians in Lebanon due to social stigma owing to their gender or sexual identity and the fact that they are Syrian.[36]Akram, “No rainbow, no integration: LGBTQI+ refugees in hiding,” Refugees in Towns Project (2019):; Will Christou, Alicia Medina, “At home and abroad, LGBT Syrians fight to have their voices … Continue reading Indeed, integration and acceptance are major struggles due to anti-Syrian sentiment among host Lebanese communities (including, at times, LGBTQ+ Lebanese) and anti-LGBTQ+ prejudice among fellow Syrians.

Since 2011, more than 1 million Syrian refugees have sought refuge in Lebanon, although only around 855,000 are currently registered with UNHCR there.[37]“Operational Data Portal: Refugee Situations,” UNHCR, (2021): https://data2.unhcr.org/en/situations/syria/location/71. LGBTQ+ Syrians are “highly vulnerable”, and more than half have reported abuse in Lebanon, though few seek help from authorities, due to fears of pervasive, institutionalised prejudice or further exploitation.[38]Amélie Zaccour, “Gay Refugees From ISIS,” The Daily Beast (2017): https://www.thedailybeast.com/gay-refugees-from-isis; “‘No place for people like you’: An analysis of the needs, … Continue reading LGBTQ+ refugees in Lebanon report that employers, abusers, and others exploit their fear of local authorities to coerce them into hostile, unsafe, and abusive professional and personal relationships.[39]One such incident involving a maintenance person is indicative of the precarity: “I started to work with someone as an air conditioner maintenance [worker]; after two weeks I asked for my money and … Continue reading While the reasons for anti-Syrian attitudes in Lebanon are complex, it is impossible to overlook the sheer scale of Syrians’ exodus to Lebanon, which has overwhelmed a relatively small national population, aggravated historical sensitivities, and strained the already fragile Lebanese state. Anti-Syrian prejudice has grown over time, fueled by the manifest failings of the Lebanese political system, violent fallout from the Syria conflict, and the legacy of Syria’s 30-year occupation of Lebanon.[40]Charbel Maydaa, Caroline Chayya, Henri Myrttinen, “Impacts of the Syrian civil war and displacement on SOGIESC populations” (2020):. To make matters worse, since October 2019, Lebanon has been gripped by significant social and economic upheaval (see: Two Countries, One Crisis: The Impact of Lebanon’s Upheaval on Syria), increasing social tensions and economic competition between Lebanese and Syrians. KIIs interviewed for this report note the pervasive sense among LGBTQ+ Syrians that Lebanon cannot be a sustainable place of refuge and is merely a transit point to Europe, North America, or Australia, where they can live without fear of state authorities or retribution from their families.

Jordan

More than any other country hosting large numbers of Syrians, Jordan is considered a “black box” in terms of LGBTQ+ issues. Negative attitudes toward LGBTQ+ individuals likely explain why there is little information available concerning LGBTQ+ Syrian refugees in the country. It is difficult to summarise the individual experiences of the LGBTQ+ Syrians who are among the 665,000 registered Syrian refugees in Jordan, although it can reasonably be inferred that anti-LGBTQ+ attitudes concerning the Jordanian LGBTQ+ community also apply to Syrians in the country. Same-sex sexual conduct was decriminalised in Jordan in 1951.[41]Waaldijk, C, “Legal recognition of homosexual orientation in the countries of the world”. Leiden University (2009): https://scholarlypublications.universiteitleiden.nl/handle/1887/14543. However, Islamic law as it is applied in the country prohibits homosexual behaviour and relationships, although no fines or penalties can be enforced under criminal law.[42]Australia: Refugee Review Tribunal, Jordan: 1. Is homosexuality illegal in Jordan (both in relation to civil law and sharia law)? 2. Is there any evidence of discrimination and/or harassment of … Continue reading De facto barriers to LGBTQ+ organising persist, however. One individual seeking Ministry of Social Development approval to create an LGBTQ+ protection initiative in the country reported firm, categorical rejection by authorities: “They took my application and threw it to the trash can in from of my eyes, while thanking me and promising to take it under consideration.”[43]Ryan Greenwood and Alex Randall, “Treading Softly: Responding to LGBTI Syrian Refugees in Jordan,” George Washington University (2015): … Continue reading

The legal ambiguity concerning LGBTQ+ behaviour in Jordan is overset by relatively unambiguous, negative prevailing social attitudes. According to a 2013 Pew public opinion survey, 97 percent of Jordanians believe homosexuality to be unacceptable.[44]“The Global Divide on Homosexuality: Greater Acceptance in More Secular and Affluent Countries” Pew Reseaerch Center (2013): … Continue reading Such attitudes have resulted in stigmatisation and harassment, violence, and honour killings. Many LGBTQ+ Jordanians are forced to leave Jordan as a consequence of negative social pressure, police mistreatment, and fear of harm from their own families due to their sexual orientation or gender identity.[45]“What’s life like for Jordan’s LGBTQ community?” The Open University (2017): https://www.open.edu/openlearn/society-politics-law/sociology/whats-life-jordans-lgbtq-community LGBTQ+ issues are widely treated by the media as taboo; when they are discussed, they are often dismissed as being part of a Western cultural agenda. In 2014, an anonymous individual published a blog post containing nearly 100 images of Jordanian men captured on Grindr and Scruff, two LGBTQ+ dating apps, in a scheme to expose their identities.[46]Khalid Abdel-Hadi, “Digital Threats and Opportunities for LGBT Activists in Jordan”. My.Kali Magazine (2016): … Continue reading The pictures were never removed, and the leak led to acts of violence toward the outed men. In 2017, a Jordanian MP told a Western reporter that homosexuals were not welcome in Jordan.[47]Olivia Cuthbert, “Jordan activists targeted after MP says gay people unwelcome”. Middle East Eye (2017): … Continue reading

Challenges

As the preceding text has made clear, LGBTQ+ Syrians face no small number of impediments to a fuller realisation of their rights, whether inside Syria or in main countries of asylum. In general, these experiences can be summarised as belonging to a number of overarching thematic areas which should, in turn, inform donor-funded aid activities, strategic advocacy, and policy considerations.

Legal Challenges

In theory, the Syrian 2012 Constitution currently in force provides guarantees for the protection of LGBTQ+ individuals and their rights and freedoms. Article 19 guarantees “respect for the principles of social justice, freedom, equality, and maintenance of human dignity of every individual.”[48]The Constitution of the Syrian Arab Republic (2012): https://www.constituteproject.org/constitution/Syria_2012.pdf?lang=en. Article 33 stipulates that citizens “shall be equal in rights and duties without discrimination among them on grounds of sex, origin, language, religion, or creed.” This freedom is described as a “sacred right”.[49]Ibid. However, the nature of Syria’s political system and the stress brought on by the protracted state of emergency lasting from 1963 to 2011[50]The emergency declaration was rolled back in an effort to quell unrest. Khaled Yacoub Oweis, “Syria’s Assad ends state of emergency,” Reuters (2011): … Continue reading have nullified these rights. On balance, the Syrian legal system is inherently hostile to LGBTQ+ individuals, who are a disfavoured class in several critical ways.

Criminalisation of Homosexuality

The most important legal framework concerning LGBTQ+ Syrians is Article 520 of the Penal Code, which criminalises “carnal knowledge against the order of nature” with a maximum penalty of three years’ imprisonment. This article has been interpreted by the Court of Cassation to encompass homosexual intercourse among males or females. Although this article has not been applied rigorously in recent years, its existence provides a basis for discriminatory attitudes, extortion, and violence against LGBTQ+ people. Syrian law also criminalises men wearing women’s clothing with the intent to enter places designated for women, as per Article 507 of the Penal Code.[51]Syrian Penal Code (1949): http://www.undp-aciac.org/publications/ac/compendium/syria/criminalization-lawenforcement/sy-penal-code.pdf. Notably, no legal provision specifically prohibits women from wearing men’s clothes for the opposite purpose, an illustration of the way that homosexual women are less visible than their male counterparts — even in legalised persecution.

Vague legal precepts concerning so-called public decency create further risk for LGBTQ+ Syrians. Article 517 stipulates a prison sentence ranging from three months to three years for violations of “public decency.” Violations have been characterised as “every act involving infringement, ridicule, or indifference to the rules of behaviour that people have become acquainted with and whose violation hurts their feelings”.[52]“Annex: Laws Prohibiting or Used to Punish Same-Sex Conduct and Gender Expression in the Middle East and North Africa,” Human Rights Watch (2018): … Continue reading The wide latitude for judicial discretion in parsing this definition makes a virtually limitless array of behaviours potentially dangerous.

Targeted Violence and Discriminaiton

Syrian law provides no protection from discrimination or violence based on sexual orientation or gender identity, creating an environment of impunity for the targeted threats and violence that are rampant.[53]“‘No place for people like you’: An analysis of the needs, vulnerabilities, and experiences of LGBTQ+ Syrian refugees in Lebanon,” Heartland Alliance International (2014): … Continue reading The law does not recognize gender groups outside of the male-female binary, which puts individuals with non-normative gender identities at heightened risk of abuse, particularly when they are required to show identifying documents.

Gender-Affirming Procedures

Gender-affirming procedures fall within a lacuna in Syrian law, leading to arbitrary and inconsistent outcomes. The judiciary has been vested with authority to approve such surgical procedures. Cases of intersex or hermaphroditism are the only legally permissible bases for surgical intervention, and only with the certification of a medical pracitioner. Gender-affirming procedures are not available in the case of psychological factors, personal desire, or identity. Notably, even when medical intervention is approved, Syrian law lacks specific provisions to conform patients’ civil and legal standing or identifying documents to their postoperative physical status. The impact of such legal gaps should not be understated. For instance, gender is used to apportion inheritance, and the lack of clarity in this area means that legally ambiguous cases must be referred to the judiciary for resolution on an ad-hoc basis. The process of correcting one’s legal name on a state ID card or other official document also runs up against challenges. The law requires that a petitioner must file a lawsuit against the civil status registrar, under Article 46 of Legislative Decree No. 26 (2007) concerning civil status. If the court approves, the correction is recorded in the Civil Status Register, and the person is granted suitable documents.

Internet Censorship

Worldwide, the internet has been instrumental in facilitating LGBTQ+ awareness and facilitating organised movements. However, with only 22.5 percent of the Syrian population using the internet in 2011, it would be an understatement to describe the arrival of the internet to the country as belated.[54]“Individuals using the internet,” World Bank: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/IT.NET.USER.ZS?locations=SY. Nonetheless, even in its early days, the internet brought LGBTQ+ Syrians into contact with global LGBTQ+ movements, furnishing a new space for understanding their identities and rights, even if access restrictions have prevented the use of the internet for effective LGBTQ+ organising and mobilisation inside Syria as the repressive security apparatus adapted to the digital sphere.

For instance, authorities require internet cafes to adhere to strict licensing procedures, including the approval of the Political Security Division at the Ministry of Interior. Internet cafes must maintain a daily registry recording personal user data, including each user’s full name, national ID number, the serial number of the device they used, and the time of their arrival to and departure from the cafe. The owners are required to provide this registry to security services if requested. In terms of online content, Article 2 of Legislative Decree No. 17 (2012) requires “internet and telecommunications service providers to save a copy of their stored content if it is available and to present it to the authorities upon request, and to save traffic data which allows verification of the identity of persons who contribute to posting content on the network”. Legislation such as this grants security agencies access to the data and identities of content publishers on the internet, including social media accounts and the content of audio, visual, or text communications. These provisions have been especially tightly enforced at internet cafes near universities and university residences.

Establishment of Associations

The 1958 Law on Associations and Private Foundations impedes formal civil society work, including for LGBTQ+ issues. The law prohibits associations or organisations licensed to support and advocate for homosexuality, which is criminalised in the Penal Code. Human rights organisations, which are advocates for LGBTQ+ issues in other countries, are de facto outlawed, and their formation is prevented by the Ministry of Social Affairs and Labour. According to this law, the Ministry of Social Affairs and Labour is responsible for approving associations, which must be done with the oversight of security agencies. Therefore, forming an association effectively requires that an application be approved by three security agencies: State Security, Political Security, and Military Security. Organisations that already operate in Syria are barred from LGBTQ+ advocacy under Decree 224 (1969), which allows for the dissolution of any previously licensed association that adopts LGBTQ+ issues.

The impact of this tight legal framework is profound. In 2018, OutRight Action International, a U.S.-based nonprofit that advocates for the rights of LGBTQ+ people around the world, reported that Syria is one of 30 countries in the world where no formal LGBTQ+ organisations could be found, whether registered or unregistered.[55]“The Global State of LGBTIQ Organising: The Right to Register” (2018): https://outrightinternational.org/righttoregister. There is no concerted advocacy for change at an institutional level. In practical terms, for LGBTQ+ Syrians, this results in a dearth of locally relevant advice, knowledge, and social support.

Peaceful Assembly and Protest

Despite token changes to legislation concerning public demonstrations following the onset of the Syrian uprising, protests are effectively banned in Syria, even if they focus on politically neutral matters, such as LGBTQ+ issues. Although the Syrian Constitution enshrines public demonstration as a fundamental right, demonstrations were outlawed under the 1963 state of emergency. The ban remained in effect until Legislative Decree No. 54 of 21 April 2011, which introduced the Law on Peaceful Demonstration. However, this law has merely perpetuated the status quo, effectively barring demonstrations through the imposition of legal and procedural hurdles that organisers view as all but impossible to overcome.

Social and Societal Challenges

Hostility on the part of families, faith communities, professional networks, and other pillars of social support is a source of precarity for LGBTQ+ Syrians, especially refugees. According to one Syrian LGBTQ+ activist, Syrian families typically do not even talk about LGBTQ+ issues, even if they are ostensibly accepting of LGBTQ+ identity: “They will say, ‘Don’t talk about it, you are fine. Just don’t talk about it’.”[56]Ammar Cheikh Omar and Yuliya Talmazan, “LGBTQ Syrian refugees forced to choose between their families and identity,” NBC News (2019): … Continue reading Media reports document instances in which the families of LGBTQ+ individuals have been ostracised, threatened, and treated with “hatred” and “revulsion” by their communities when their relatives have expressed LGBTQ+ identity openly when living abroad.[57]Ammar Cheikh Omar and Yuliya Talmazan, “LGBTQ Syrian refugees forced to choose between their families and identity,” NBC News (2019): … Continue reading It is therefore not surprising that families of LGBTQ+ Syrian refugees sometimes disown their children, cut off communication, and have even expressed a preference for their children to have perished while fleeing Syria, rather than living in a way that could bring unwelcome attention to the family.[58]Ibid.; Ban Barkawi, “’I wish they killed you’: trauma of Syrian LGBT+ rape survivors,” Reuters … Continue reading

With formal political or social mobilisation legally impeded, LGBTQ+ Syrians have been divided along prevailing social, economic, and political lines, according to advocates interviewed for this report. For instance, some LGBTQ+ Syrians have called attention to the divisions among Syrian homosexual men over attitudes concerning perceived masculinity and femininity.[59]Ayman Menem, “Voices breaking the silence: Fighting for personal freedoms and LGBTIQ rights in Syria,” Syria Untold (2020): https://syriauntold.com/2020/11/03/voices-breaking-the-silence/. Religiosity also shapes LGBTQ+ circles; in the eyes of many Syrians, a person cannot be both homosexual and religious.[60]“Why my own father would have let IS kill me” BBC News (2015) https://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-33565055. Religious LGBTQ+ individuals are therefore sometimes subject to prejudice from the LGBTQ+ community, whose members often view the rejection of religiosity as a precondition for LGBTQ+ identity. Similar challenges confront lesbians and trans women who wear the veil, which is frequently criticised as a vehicle of patriarchal oppression.[61]The acceptability of various forms of veil is a subject of intense debate on which few universal principles can be resolved. Among them is the reality that a wearer’s choice should be paramount. … Continue reading While all LGBTQ+ individuals face stigma in Syria, this is perhaps even more pronounced for women because of a widespread view that women carry (and therefore risk) the collective honour of the family.[62]Ibid. In some cases, women who are open about their non-normative sexual identity are barred from communicating outside the family; they may face violence, harmful “treatments” such as conversion therapy, or be forced into marriage. Social expectations over marriage lead (or force) many LGBTQ+ Syrians to marry and begin a family, despite the personal and emotional cost of leading a double life.[63]Reese Erlich, “Gays join the Syrian uprising,” DW (2012): https://www.dw.com/en/gays-join-the-syrian-uprising/a-16216661; Hannah Lucinda Smith, “How Jihadists are blackmailing, torturing, and … Continue reading

Sources point to further social divisions that reflect Syria’s deeply divided political culture. They note that LGBTQ+ individuals within the Syrian upper class have enjoyed a degree of liberty in violating the prevailing moral order that is otherwise hostile to LGBTQ+ individuals. For such individuals, the relative freedom and protection they enjoy serve as evidence of the extent to which Syria’s ruling elite stands apart from society at large. For instance, when the popular uprising erupted in 2011, affluent Damascene gay men were well-known within LGBTQ+ circles for hosting LGBTQ+ parties at farms and villas near the capital, under the watchful observation — and implicit protection — of authorities. Among the known hosts of these parties was the homosexual son of an individual within the most powerful inner circle in Damascus.[64]According to multiple KIIs and reliable anecdotes circulating among gay men from Damascus, as disclused during interviews conducted for this report. In general, the cultural elite in Syria’s most cosmopolitan cities, Damascus and Aleppo, have shown some toleration for semi-overt expressions of homosexual identity, yet this acceptance has been extended only to the privileged few, and it has not translated to a recognition or acceptance of collective LGBTQ+ identity more broadly.

On the other end of the spectrum, LGBTQ+ individuals from the social and economic lower classes have experienced a modicum of freedom because of the very neglect that has led to their marginalisation. Whereas ruling class LGBTQ+ Syrians have enjoyed relative liberty as a result of their power and influence, lower-class Syrians have skirted accepted norms precisely because of their low profile.[65]According to KIIs with LGBTQ+ activists. In 2011, the open presence of trans women or feminine homosexual males in the urban slums surrounding Damascus was so normalised as to suggest some degree of popular indifference.[66]Aram Midani, “Terminology and Secrets of the LGBTQ Community in Syria”. Raseef 22 (2021): . Unlike LGBTQ+ individuals from the elite set, however, these individuals and LGBTQ+ Syrians of the middle class remain acutely vulnerable, as their LGBTQ+ identity can be weaponised against them by state authorities, acquaintances, or other opportunistic actors.

Security and Protection

Inside Syria and in countries of asylum, protection and security are paramount concerns for LGBTQ+ individuals, who generally qualify for refugee status as “members of a particular social group” under the 1951 Refugee Convention.[67]“LGBTI People,” UNHCR, https://www.unhcr.org/tr/en/lgbti-people Human Rights Watch and others have documented forms of conflict-related violence that include sexual harassment, genital mutilation (beating, electric shock, and burning), rape, forced nudity, and threats of rape against individuals or their family members.[68]“They treated us in Monstrous Ways,” Human Rights Watch (2020): https://www.hrw.org/report/2020/07/29/they-treated-us-monstrous-ways/sexual-violence-against-men-boys-and-transgender; “Report of … Continue reading In a 2014 study of LGBTQ+ Syrians in Lebanon, a staggering 96 percent of respondents reported being threatened in Syria because of their gender or sexual identity; 54 percent reported being assaulted for the same reason.[69]“‘No place for people like you’: An analysis of the needs, vulnerabilities, and experiences of LGBTQ+ Syrian refugees in Lebanon,” Heartland Alliance International (2014): … Continue reading Especially troubling is the risk of extortion of LGBTQ+ Syrians by opportunistic individuals, militias, or organised criminal networks. LGBTQ+ Syrians have reported being blackmailed and even kidnapped for ransom, including repeat attacks by the same actors.[70]Hannah Lucinda Smith, “How Jihadists are blackmailing, torturing, and killing gay Syrians,” Vice.com (2013): https://www.vice.com/en/article/gq8b4x/gay-syrians-are-being-blackmailed-by-jihadists In other cases, Government of Syria security agents and Islamist armed group combatants have posed as gay men on social media or dating applications in order to entrap LGBTQ+ individuals — a process that has sometimes culminated in in-person meetings leading to arrests, kidnappings, beatings, blackmail, ransom demands,[71]Amélie Zaccour, “Gay Refugees From ISIS,” The Daily Beast (2017): https://www.thedailybeast.com/gay-refugees-from-isis and even killings.[72]James Kirchick, “ISIS Goes Medieval on Gays,” The Daily Beast (2015): https://www.thedailybeast.com/isis-goes-medieval-on-gays As illicit war economies proliferate inside Syria, the risk of extortion over sexual or gender identity will grow. Because few of these risks are directly related to active major combat operations, the resulting protection concerns can be expected to persist irrespective of the state of the conflict.

Security and protection risks are also present in countries of asylum. UNHCR considers LGBTQ+ persons to be “extremely vulnerable” because they have a justified fear of persecution by hostile host communities as well as conventional sources of support for refugees, which include families, other refugees, and aid workers.[73]Graeme Reid, “The Double Threat for Gay Men in Syria,” Human Rights Watch (2014): https://www.hrw.org/news/2014/04/28/double-threat-gay-men-syria Although same-sex relationships are legal in Turkey, homophobic attitudes are nonetheless widespread and LGBTQ+ refugees have reported troubling incidents, including being pelted with rocks or being followed in the street and attacked.[74]Neil Grungras, Rachel Levitan, and Amy Slotek, “Unsafe Haven: Security Challenges Facing LGBT Asylum Seekers and Refugees in Turkey,” PRAXIS The Fletcher Journal of Human Security (2011) … Continue reading The apparently targeted murder of LGBTQ+ Syrians is a further cause for concern. For instance, in 2016, Muhammed Wisam Sankari, a young gay Syrian refugee, was found killed in Istanbul, his body mutilated. Sankari had previously told police that he feared for his life, after having previously been abducted, tortured, and raped by unknown assailants.[75]“Missing gay Syrian refugee found beheaded in Istanbul,” The Guardian (2016): … Continue reading In June 2019, another gay refugee, 22-year-old Muhammad Hamsho, was stabbed to death in Mersin, in southern Turkey.[76]According to several friends of the victim. The incident was poorly reported in the media but is well known to the Syrian refugees in Mersin, Turkey — especially members of the LGBTQ+ community in … Continue reading

In Lebanon, the formal illegality of homosexuality amplifies the broader social hostility and discrimination facing Syrian refugees.[77]“Syria crisis: What is it like to be a gay refugee?” BBC News (2014): https://www.bbc.com/news/av/world-middle-east-29789498. The Lebanese Office for the Prevention of Crimes against Public Decency has been accused of targeting gay men[78]Joey Ayoub, “Lebanese Police Arrest Four During Gay Club Raid,” Global Voices, 2013, https://globalvoices.org/2013/05/08/lebanon-scandal-breaks-out-over-homophobic-raid-in-dekwaneh/ and performing illegal and purposefully humiliating abuse, including reported use of “anal tests” — which have been banned by a recent decree and were described by the Lebanese Doctors Syndicate as a form of torture.[79]“Dignity Debased: Forced Anal Examinations in Homosexuality Prosecutions,” Human Rights Watch (2016): … Continue reading Although Lebanese navigating arbitrary interactions with authorities sometimes have recourse to family networks, influential political party members, or other trusted intermediaries capable of preventing harsh and arbitrary punishment or detention, Syrian refugees seldom have access to such mechanisms.

Politics

LGBTQ+ rights are among the broad swath of basic human rights that are truncated in Syria’s political system. The Assad regime has purposefully instrumentalised and manipulated political, cultural, social, religious, and other fissures to further its own rule. A pivot toward conciliation with LGBTQ+ Syrians, yet it would ring hollow in the context of Bashar al-Assad’s greater attempts to marry the state and traditional religious establishment.[80]“Syria Chapter – 2015 Annual Report,” Tolerance Project (2015): https://tolerance.tavaana.org/en/content/syria. Advocates have called for the legal protection of LGBTQ+ Syrians via constitutional and legal reform. No doubt, such protections are badly needed, but they would represent merely the first step of many toward full equality. Reducing the legal vulnerability of LGBTQ+ Syrians is important, but substantive change to social norms is unlikely to take root unless a movement is fostered through means that are inclusive, democratic, and bottom-up.

Healthcare

All Syrians have borne the consequences of the decimation of Syria’s health infrastructure after 10 years of conflict, but LGBTQ+ individuals face additional burdens due to acute health disparities, mental health burdens, HIV/AIDs risk, among other needs.[81]Tonya Littlejohn, Tonia Poteat, and Chris Beyrer, “Sexual and Gender Minorities, Public Health, and Ethics,” The Oxford Handbook of Public Health Ethics (2019): … Continue reading The conflict has prompted the flight of 70 percent of Syrian healthcare workers, and the destruction of infrastructure has left only half the country’s public hospitals fully operational.[82]Mazen Gharibah and Zaki Mehchy, “COVID-19 Pandemic: Syria’s Response and Healthcare,” Conflict Research Program at LSE, (2020): … Continue reading Meanwhile, medical supplies, pharmaceuticals, and health facility equipment are frequently inadequate — an issue that COVID-19 has only aggravated (see: Syrian Public Health after COVID-19: Entry Points and Lessons Learned from the Pandemic Response). LGBTQ+ patients’ health access and outcomes are limited by factors such as discrimination by healthcare providers, systemic knowledge gaps, and patients’ trepidation.[83]“LGBTQ and Health Care: Advocating for Health Access for All,” Tulane University School of Public Health and Tropical Medicine (2019): … Continue reading Moreover, advocates have called attention to a hostile tendency within clinical settings that is perpetuated by the use of a “vocabulary of deviance, illness or mental disturbance to describe homosexuality”.[84]Ayman Menem, “Voices breaking the silence: Fighting for personal freedoms and LGBTIQ rights in Syria,” Syria Untold (2020): https://syriauntold.com/2020/11/03/voices-breaking-the-silence/. Such impediments must be overcome if LGBTQ+ Syrians are to close the health access gap.

Particular challenges for LGBTQ+ Syrians in countries of asylum differ according to location. In Turkey, access to public healthcare networks and the operation of migrant health centers staffed by Syrian doctors are central pillars of the refugee health assistance efforts, which have been formalised through the Temporary Protection (TP) system established there in 2014.[85]“Temporary Protection in Turkey,” UNHCR: https://help.unhcr.org/turkey/information-for-syrians/temporary-protection-in-turkey/. Nonetheless, Syrian refugees encounter a number of difficulties when seeking healthcare — including language barriers, bureaucratic and registration obstacles, discrimination, overburdened facilities, and hard-to-predict changes to policies.[86]Gabriele Cloeters and Souad Osserian, “Healthcare access for Syrian Refugees in Istanbul: A gender-sensitive perspective,” Istanbul Policy Center (2019): … Continue reading State healthcare provision is inaccessible to unregistered refugees. As a result of these factors, a dynamic landscape of informal clinics and medical centres run by Syrian doctors has emerged to provide care to unregistered refugees and those otherwise unable to access the Turkish state-run healthcare system. LGBTQ+ Syrians with TP status have access to free healthcare, including treatment for chronic illnesses such as HIV and Hepatitis B, which require costly life-saving medication. However, stigma due to gender or sexual identity can be a barrier to access.

In Lebanon, a number of local NGOs providing healthcare, mental health and psychosocial support (MHPSS), and social services are known for being gay-friendly, but the system as a whole is strained beyond capacity.[87]As with other organisations referenced in this report, the identities of these NGOs have been omitted in order to avoid calling attention to their work. Further exacerbating the service challenge for Syrians is the fact that Lebanon does not allow relief organisations to operate formal refugee camps or field hospitals. Refugee medical needs must therefore be met by the ailing, underfunded Lebanese healthcare system.[88]Catarina Hanna-Amodio, “Syrian refugee access to healthcare in Lebanon” Action On Armed Violence (2020): https://aoav.org.uk/2020/syrian-refugee-access-to-healthcare-in-lebanon/. In Beirut, only three medical centers provide healthcare for registered Syrian refugees.[89]“List of Hospitals For All Asylum Seekers and Refugees in Lebanon” UNHCR (2021): http://www.refugees-lebanon.org/uploads/poster/poster_161771013515.pdf. In general, reports indicate that LGBTQ+ Syrians dealing with sexually transmitted infections, the trauma of sexual violence, and other needs, in Lebanon are more likely than other patients to avoid seeking out needed medical care, due to the associated stigma.[90]Khairunissa Dhala, “Gay Syrian refugees struggle to survive in Lebanon,” Amnesty International (2014): … Continue reading

In Jordan, primary healthcare risks concern access, in particular concerning HIV/AIDS testing and treatment. HIV/AIDS-positive individuals are at risk of deportation; this vulnerability creates a perverse disincentive for individuals to seek HIV/AIDS testing or treatment, which may increase the risk of transmission within the wider, non-refugee population.[91]Ryan Greenwood and Alex Randall, “Treading Softly: Responding to LGBTI Syrian Refugees in Jordan,” George Washington University (2015): … Continue reading Issues such as these are exacerbated by the far-reaching repression of LGBTQ+ organisations in Jordan. Despite the absence or inadequacy of state service provision for LGBTQ+ persons across sectors, NGOs seeking to cover these gaps have been dismissed by authorities, leaving vulnerable individuals to navigate a patchy and inadequate state support system.[92]Ibid.

Mental Health

As with healthcare more broadly, the effects of conflict on mental health in Syria have been profound. Although these conditions affect the entire population, LGBTQ+ persons must confront a known mental health disparity.[93]Tonya Littlejohn, Tonia Poteat, and Chris Beyrer, “Sexual and Gender Minorities, Public Health, and Ethics,” The Oxford Handbook of Public Health Ethics (2019): … Continue reading For LGBTQ+ Syrians, vulnerabilities related to sexual exploitation, substandard housing, stigma, discrimination, heightened poverty, the lack of appropriately tailored services or aid, and the loss of family and community support are additional burdens that drive mental health needs.[94]“Syrian refugees in Lebanon misses help dealing with psychological trauma,” Dignity Danish Institute Against Tourture (2018): … Continue reading In a survey of LGBTQ+ Syrians in Lebanon, 58 percent described their mental health as “poor,” a figure that is likely indicative of urgent need across relevant contexts.[95]“‘No place for people like you’: An analysis of the needs, vulnerabilities, and experiences of LGBTQ+ Syrian refugees in Lebanon,” Heartland Alliance International (2014): … Continue reading Anecdotal reports indicate that many Syrian LGBTQ+ refugees have considered or attempted suicide — a phenomenon noted among LGBTQ+ commmunities globally. Currently, MHPSS support for Syrian refugees in general is limited, and priority is given to victims of trauma, torture, and conflict, while LGBTQ+ identity is seldom if ever used as a targeting criteria.

Economics and Labour

Discrimination, societal norms, and conventional gender roles in the workforce compound the challenges facing LGBTQ+ Syrians seeking sustainable livelihoods. This is true both inside Syria, where economic decline has left 90 percent of the population in poverty, and in neighbouring countries. LGBTQ+ Syrians face hiring discrimination and abuse in the workplace; and the hostility of landlords and neighbours. Heightened economic precarity increases the likelihood of other risks, including transactional sex and unsafe housing.

In Turkey, the modest labour prospects, grim working conditions, and poor wages facing all Syrian refugees — often in textile mills — have driven some LGBTQ+ Syrians in the country to sex work.[96]Emel Altay, “Syrian LGBTI refugees struggle in Turkey,” Journo (2018): https://journo.com.tr/syrian-lgbti-refugees-struggle-in-turkey In the absence of hard statistics, there is anecdotal evidence suggesting that Syrian trans women in Turkey face acute pressure to engage in sex work as a primary income strategy. Likewise, young gay Syrian refugees are known to work as “rent boys” — frequenting cafes, bars, and hammams in particular neighbourhoods in Istanbul.[97]According to KIIs with NGO workers in Turkey. Limited protection strategies are available to these refugees, who avoid working in the open due to their fear of organised criminal gangs and who often use social media to find clients. Turkish NGOs seeking to help these refugees face significant challenges, and beneficiaries are pressured by the police and state authorities, gangs, and pimps.

In Lebanon, as a result of tight labour restrictions and residency policies, only Syrians who are registered as refugees are allowed to work legally — and, even then, only in certain low-skilled sectors (e.g., construction and agriculture).[98]“Lebanon: Residency Rules Put Syrians at Risk,” Human Rights Watch (2016): https://www.hrw.org/news/2016/01/12/lebanon-residency-rules-put-syrians-risk; “Lebanon Events of 2017,” Human Rights … Continue reading Those with higher qualifications find it extremely challenging to obtain work permits that entitle them to work in a job that accords with their credentials. These conditions, alongside the high cost of living, prohibitively expensive administrative fees, barriers to healthcare and services, and the economic slowdown — brought on by the nation’s economic crisis and COVID-19 restrictions — make Syrians extremely vulnerable to exploitation and pressure to engage in sex work.[99]“The Syrian refugees selling sex to survive in Lebanon,” BBC News, (2017): https://www.bbc.com/news/av/world-middle-east-39403276

Aid

Aid workers are reportedly generally willing to provide greater support to LGBTQ+ beneficiaires, but relevant training has been inadequate, and stereotypes, prejudice, and misinformation are pervasive among providers.[100]“‘No place for people like you’: An analysis of the needs, vulnerabilities, and experiences of LGBTQ+ Syrian refugees in Lebanon,” Heartland Alliance International (2014): … Continue reading Anecdotally, Syrians interviewed for this report describe hesitancy to disclose their LGBTQ+ identity when registering with UNHCR and other aid actors out of fear of stigma. Some indicate that service providers have raised doubts over their gender or sexual identity, or were otherwise insensitive to their needs.

Recommendations

The need areas highlighted for donor-funded programming outlined below stand as partial answers to the complex challenges facing LGBTQ+ Syrians. This list is by no means definitive or complete; it is meant to highlight donor-funded activities that are both realistic and capable of supporting meaningful improvements in the lives or circumstances of LGBTQ+ Syrians. Regrettably, not all of the most pressing challenges that exist can be addressed through aid or relief work. Some of the areas of greatest need, such as legal and political challenges, lie out of reach. Nevertheless, incremental, targeted approaches can have a significant impact, even in the absence of comprehensive solutions.

Boost Healthcare

Foreign donors and aid actors have a limited toolkit available to directly improve healthcare outcomes for LGBTQ+ individuals inside Syria, particularly in Government of Syria areas, where political concerns inhibit coordination or cooperation with state-linked organisations and Damascus-based line ministries. However, initiatives to improve healthcare access and quality for all Syrians can reduce the pressure that disproportionately affects LGBTQ+ individuals, allowing them to exercise greater choice and avoid latent discrimination within the healthcare system. More targeted approaches are also possible; across Syria’s regions and in neighbouring states, telemedicine is one option for expanding high-quality LGBTQ+ specific care with a greater degree of confidentiality.

In countries of asylum, efforts should be made to advocate for strengthening healthcare access for Syrians, including LGBTQ+ people. Such access is particularly vital for HIV/AIDS patients and trans persons who require pharmaceutical care. In Turkey, barriers to health access including bureaucratic red tape, poor information access, language barriers, and other factors can be addressed through support for medical interpreters, support staff, information centres, physician training, and greater health sector integration and credentialing for trained Syrian healthcare workers. In Lebanon, strengthening the health services provided by NGOs directly, including relevant LGBTQ+ services, would relieve pressure on the stressed national healthcare infrastructure, which is currently at risk due to medical sector debts that the Lebanese state cannot pay. Although UNHCR coordinates support with relevant ministries and organisations and covers up to 75 percent of the cost of refugee healthcare,[101]“Health access and utilization survey among Syrian refugees in Lebanon – November 2017,” UNHCR (2017): … Continue reading financial shock and the COVID crisis have eviscerated the hospital and clinic network in Lebanon. Every effort should be taken to ensure that Syrians, including LGBTQ+ refugees, are not the victims of the collapse of Lebanon’s health system.

Bolster Sexual Health Education

Aid providers should support greater sexual health awareness for LGBTQ+ individuals, including via community-oriented organisations and online platforms, as appropriate. Anecdotal evidence indicates that inadequate safe-sex knowledge and practices in Syrian LGBTQ+ communities create heightened risk, especially for individuals adapting to cosmopolitan environments such as Istanbul, Beirut, and many Western places of asylum. Syrian public schools employ substandard educational curricula concerning LGBTQ+ issues and STIs, including HIV/AIDS. Syria has a low prevalence of HIV/AIDS,[102]“Syria is a low prevalence rate country for HIV/AIDS but in spite of this, efforts to tackle the issue are being stepped up,” The New Humanitarian (2005): … Continue reading although the Ministry of Education has adopted a limited HIV/AIDS curriculum for secondary school to raise awareness of the condition and its transmission. Nonetheless, sources interviewed for this report indicate that HIV/AIDS awareness among LGBTQ+ Syrians abroad is inadequate, while the stigma surrounding the conditions is enormous. Public health education and awareness campaigns may help reduce both stigma and infections.

Target LGBTQ+ Syrians for Mental Health and Psychosocial Support

LGBTQ+ Syrians report disproportionately poor mental health status, and should be targeted for MHPSS support on this basis. MHPSS assistance is currently being provided to Syrians by NGOs in Turkey, Lebanon, and Europe through psychotherapy, talk therapy, and counselling programming.[103]“European Journal of Public Health, Volume 29, Issue Supplement_4”, (2019): https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckz185.579 and Dana Sleiman and Dalia Atallah, “With Syria refugee crisis, Lebanese … Continue reading More should be supported, given studies that indicate an outright majority of LGBTQ+ Syrian population have poor mental health. Remote telemedicine may extend the reach of relevant programming to an LGBTQ+ patient population not only in countries of displacement but inside Syria as well. Remote services may also reduce feelings of stigma and beneficiary reluctance stemming from negative experiences in conventional clinical settings. Finally, equipping MHPSS providers with relevant LGBTQ+ training can improve the quality of care provided.

Legal Barriers Are Unlikely to Fall Soon

Legal reforms are desperately needed, particularly regarding civil documentation, national IDs, and procedural matters that can impact LGBTQ+ Syrians’ participation in public life and access to services. However, there is currently little space to advocate for changes to Syria’s legal code. LGBTQ+ Syrians have considered avenues for legal reform,[104]Ayman Menem, “Voices breaking the silence: Fighting for personal freedoms and LGBTIQ rights in Syria,” Syria Untold (2020): https://syriauntold.com/2020/11/03/voices-breaking-the-silence/. including the Syrian Constitutional Committee process and strategic litigation in the nation’s court system, but these are — for now — likely to be dead ends. Education and advocacy concerning such matters may have an edifying effect on marginalised Syrian LGBTQ+ individuals and improve the communities’ visibility, but major legal reforms remain improbable under the current legal regime, a skepticism shared by many LGBTQ+ Syrians.

Support Social Progress Where Possible

The struggle for LGBTQ+ rights in Syria overlaps with other social questions and, if avenues for legal change are narrow, there is value in endeavouring to address related social issues. Indeed, legal reform has little chance of making positive change without accompanying normative shifts. By way of example, we can look to Bahrain, where the persistent social stigma around homosexuality — despite its decriminalisation — is a lesson on the “stickiness” of social norms concerning LGBTQ+ issues. Conversely, in Lebanon, judges have at times invoked evolving social mores in their decisions not to prosecute homosexual acts. Lebanon’s example offers evidence of the importance of social progress as a cornerstone of the eventual, albeit gradual, legal space for LGBTQ+ persons in the region. Particular areas of social advancement are noted below:

Break the Silence: LGBTQ+ Activism

LGBTQ+ Syrians face tremendous social pressure to conceal their sexual orientation or gender identity. Even when LGBTQ+ individuals are forthright concerning these matters, their friends or family members often urge them to remain in the closet. Boosting the profiles of LGBTQ+ Syrians, whether inside the country or in the diaspora, will be critical to shattering the LGBTQ+ taboo.[105]“Audacity in Adversity: LGBT Activism in the Middle East and North Africa” Human Rights Watch (2016): … Continue reading Moreover, building linkages between LGBTQ+ Syrians and global LGBTQ+ movements may begin to address a sense of alienation and abandonment that KIIS and survey respondents overwhelmingly reported.

Foster Community

Even where it is too risky for activists to operate through formal organisations, work is ongoing to create safe spaces where LGBTQ+ Syrians can come together, find support, and speak candidly about issues affecting them. Such work can and should be supported. Online platforms may provide a vehicle for collectives and platforms, particularly in countries bordering Syria. An example of one initiative of this type is a project in Cairo to gather oral histories of LGBTQ+ people in Egypt and the wider region. Although the project has the benefit of informing and educating non-LGBTQ+ people, its primary aim is to provide affirmation and a sense of community for LGBTQ+ people, in part through a safe online environment. In countries of asylum, building greater connections between LGBTQ+ Syrians and LGBTQ+ persons within the host community can be a powerful means of reducing the sense of alienation that many Syrian sexual and gender minorities report.

Build Alliances

Partnerships with organisations focused on adjacent issues, such as human rights and women’s rights, may boost the interests of LGBTQ+ people. For example, in the Kurdistan Regional Government areas of Iraq, Rasan, a women’s rights organisation, formally included LGBTQ+ rights in its mandate in 2012. Activists across the region say that building alliances with feminist and human rights organisations will require concerted efforts and flexibility on all sides. Chouf, a feminist organisation in Tunisia that works with women of all sexual identities, also broadened its mandate after LGBTQ+ women advocated from within. Meanwhile, the Helem organisation in Lebanon primarily focuses on LGBTQ+ rights, but it has broadened its agenda to situate itself within the broader civil rights movement and it collaborates with organisations working on issues as wide-reaching as corruption, pollution, and labour rights.

Increase Support for Livelihoods, Shelter, and Protection

Facing widespread employment discrimination, LGBTQ+ Syrians are saddled with acute economic precarity. Targeting LGBTQ+ individuals for livelihoods or cash assistance can reduce the knock-on consequences of poverty, which include unsafe housing conditions, forced sex work, and trafficking, all of which carry attendant protection risks. Similarly, targeting LGBTQ+ persons for shelter and housing activities can reduce the pressure to enter the labour market for unsafe work. All such approaches can reduce risky behaviour. Protection activities that are sensitised to the concerns of LGBTQ+ persons should also be considered.

Aid Actors Must Mainstream LGBTQ+ Sensitivity Procedures across Sectors