In-Depth Analysis

On 9 July, the UN Security Council voted unanimously to extend the mandate granting UN aid access to northwest Syria from Turkey, through the Bab al-Hawa border crossing. The resolution, 2585, extends the cross-border aid system’s mandate for six months, with another six-month extension contingent on a substantive assessment by the Secretary General. As such, the UN-based aid architecture that underpins the cross-border crisis response in northwest Syria will be insulated against lobbying by its chief opponent, Russia, for a full year. The system was due to lapse on 10 July, and the contentious, last-minute vote followed months of intense diplomatic bargaining to coax Moscow to support extension. The US and others had sought not only to extend access, but to expand it to other crossings, in recognition of growing humanitarian needs across the country. While the “compromise resolution” has been welcomed as a “rare moment of unanimity” concerning Syria, it has also faced criticism, and it has been denounced as a manipulation of Syrians’ suffering for political purposes. All told, the vote defers Security Council deliberation over the mechanism for another year, but the Syria crisis response must not become complacent. There are signs that Russia’s acquiescence will provide the basis for fiercer opposition to the mechanism in the future.

A win for Syrians, but what does Russia get?

Although positive news for conflict-affected Syrians has seldom come from midtown Manhattan, the Security Council vote is a clear, direct victory for the Syria crisis response after months of uncertainty. The presumptive extension of the cross-border system for another 12 months will spare Syrians in Idleb the catastrophic loss of a lifeline — for now. Future renewal cannot be taken for granted, however. Since the system’s creation in 2014, Russia has deftly wielded the threat of a veto to extract concessions that support its interpretation of state sovereignty and which benefit its Damascus allies.

Although the mandate’s renewal is a boon to civilians in northwest Syria and the major donor states seeking to support them, Moscow does not walk away empty-handed. Putatively in response to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on Syria’s health system, the updated resolution pledges to “improve cross-line deliveries of humanitarian assistance” and calls for “full, safe and unhindered humanitarian access, without delay … to all parts of Syria without discrimination.” Such clauses reflect Moscow’s contention that Government of Syria areas are underserved and must receive a greater share of aid. It will also be seen as a concession by Washington that on 28 June, US Secretary of State Anthony Blinken announced $436 million of additional support to Syria. This followed comments from US officials that Washington intends to extend pandemic relief and vaccine support to all of Syria’s regions, including Government-controlled areas, a win for Damascus and Moscow alike.

The resolution also contains provisions for reporting and data sharing that may provide fodder for future Russian ambitions to dismantle the UN-based cross-border aid system. Now, more detailed reporting updates will be required concerning implementing partners, beneficiary data, and distribution locations. Perhaps equally notable is the resolution’s unambiguous emphasis on boosting “early recovery projects.” Early recovery activities designed to sustainably boost local livelihoods will no doubt be an important part of Syria’s eventual post-war recovery. They may also be an important instrument in donors’ toolkits to achieve targeted, lasting impact in Syria. However, there are important questions to be raised over Russia’s definition of early recovery, which likely differs from that used by major donors. Sequencing is also a matter of concern. Overall, carrying out early recovery activities now may approach — or cross — a red line for many donors, given the lack of progress toward a sustained resolution of the conflict. A failure to execute an early recovery agenda at scale, as Moscow desires, will provide the basis for future Russian objections to the cross-border mandate as a whole. Armed with more granular data, Russia may also be more effective in its argument that the mandate provides outsize support in favour of the population of opposition areas.

Cross-border access: The once and future innovation

The vote spares consideration of aid architecture without the cross-border mechanism at its core. Within the Syria crisis response, it has become axiomatic that there is simply no alternative to cross-border aid delivery as a means of reaching the 3.4 million people in need in northwest Syria. At the time of its passage in 2014, the authorisation permitting the UN to orchestrate cross-border aid convoys, UN Security Council Resolution 2165, marked a paradigm shift in the Syria crisis response. A repudiation of the state-based UN system itself, the resolution was a subtle but profound innovation. It allowed UN convoys to reach outlying areas of Syria by circumventing central government authorities, who had systematically blocked access through byzantine permitting requirements, dubious security restrictions, and concerted efforts to weaponise aid to undermine opposition areas and punish disloyal populations.

Over time, Russia has wielded the threat of its Security Council veto to systematically narrow the system’s scope. Since 2019, Moscow has succeeded in shutting down three of the four original crossings, leaving only Bab al-Hawa in operation. Other crossings — al-Ramtha in the south, al-Ya’robiyeh in the northeast, and Bab al-Salameh in northern Aleppo — were previously shuttered to UN convoys due to Russian pressure in the Security Council. In the months leading up to latest vote, Moscow contended that unfettered UN access via Bab al-Hawa without the consent of the Government of Syria violates the bedrock principle of territorial sovereignty and unfairly advantages opposition areas at the expense of people in Government-held territory, which has a larger number of people in need. In place of the cross-border aid delivery mechanism, Russia has instead advocated for the reliance on cross-line aid delivery. Such a system would re-route not only aid but also donor funds through Damascus-based UN agencies. Implicitly, such a system would place financial, political, and logistical considerations for UN aid in the country at the mercy of the Government of Syria.

The future of the Syria crisis response

It is incumbent upon donors, aid actors, and others involved in Syria crisis response to consider alternatives to cross-line aid delivery, should Russia impede renewal of the cross-border mechanism in one year’s time by imposing insurmountable conditions. Cross-line aid delivery in Syria cannot be carried out effectively at scale, or in accordance with humanitarian principles. Damascus has frequently weaponised aid (in particular, the UN convoy system) as the inducement in its “stick and carrot” military strategy to defeat the opposition and force besieged populations to capitulate. Even today, former opposition areas now under Government control face disparities in service delivery and state support, an explicit punishment for rising up against Damascus (see: ‘Arrested Development’: Rethinking Local Development in Syria). Alternatives to a cross-border system orchestrated by the UN are available, but donors and implementers alike have grown complacent, convinced that the current system’s importance to northwest Syria would ensure its continued renewal. That is no longer a safe assumption. More work must be done to ensure that vulnerable Syrians’ lives do not hang in the balance.

Whole of Syria Review

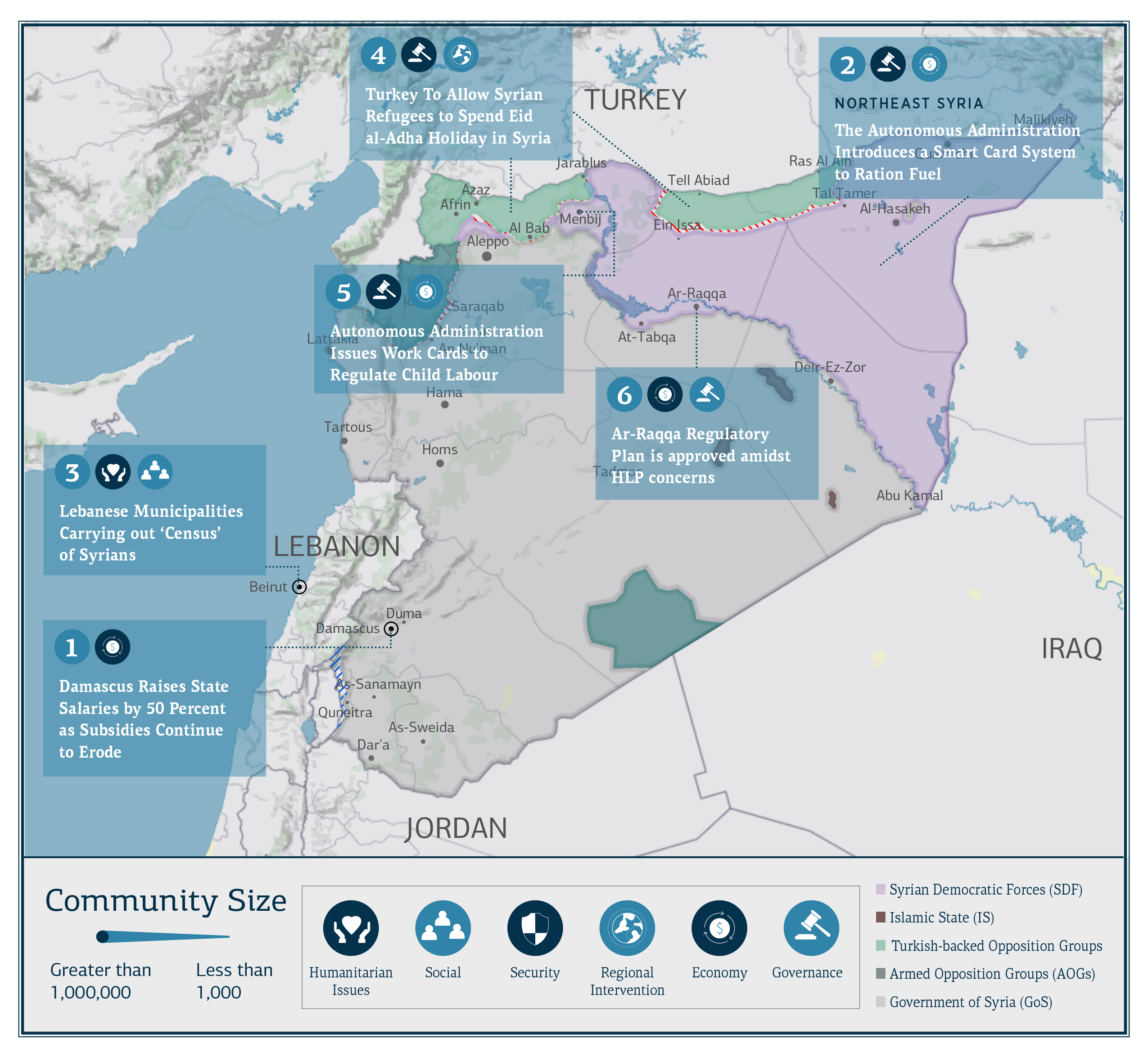

Damascus Raises State Salaries by 50 Percent as Subsidies Continue to Erode

Damascus: On 11 July, the Government of Syria raised the salaries of state employees and military personnel by 50 percent. The increase is the first pay bump for state employees since 2019. The increase was preceded by steep reductions to fuel subsidies. On 7 July, the Ministry of Domestic Trade and Consumer Protection raised the litre price of unsubsidised 95 octane fuel from 2,500 to 3,000 SYP (approx. 92 US cents), the third increase this year. Smart card allocations are unable to meet demand, and scarcity has pushed the black-market price as high as 4,000 SYP per litre.

The Band-Aid effect

The pay rise gives state employees a needed boost by raising the wage floor, but it will not substantially or durably improve consumer purchasing power or offset the cycles of socioeconomic degradation which have become routine in Government-controlled areas. The minimum wage is now roughly 75,000 SYP (approx. 22.86 USD) whereas the kilo price of red meat is roughly 26,000 SYP in Damascus at the time of writing. Perversely, the pay bump may drive further price inflation. Without serious improvement to fiscal management, salary rises contribute to fears of further currency depreciation, too. In the long term, Syrians will be strained to find supplemental income sources, including remittances, the war economy, and the aid sector. (For more on the impact of the economic crisis on Syria’s labour market, see: The Syrian Economy at War: Labor Pains Amid the Blurring of the Public and Private Sectors).

The Autonomous Administration Introduces a Smart Card System to Ration Fuel

Northeast Syria: On 28 June, the Autonomous Administration announced that it would move forward with a smart card system for allocating diesel and petrol, previously sold at below-market rates. The new system aims to prevent tampering with the amount of fuel allotted to individuals under the Autonomous Administration’s jurisdiction, and to curb the sale of subsidised oil products on the black market, particularly to Government areas, where prices are significantly higher and rising. As of 9 July, the Autonomous Administration has not indicated who will be eligible to apply for the card, or if there will be reductions to the allotted amounts.

Controlling supply at any cost

The introduction of the smart card system may indicate that the Autonomous Administration is looking to control costs and head off potential shortages in refined oil products. Despite controlling Syria’s largest oil fields, it continues to rely on to a large extent on Damascus for refining capacity (see: Infographic: Northeast Syria Trade Dynamics). The new decision comes on the heels of the Autonomous Administration’s 18 May capitulation to deadly protests against an earlier decision to raise the prices of oil products (see: Syria Update 24 May 2021). The proposed increase would have nearly tripled the prices of cooking gas cylinders and petrol, which the Autonomous Administration justified as a response to market conditions. The smart card system might allow for more flexibility in setting prices and allocations, as opposed to the blanket increase proposed in May. Still, it remains doubtful that the Autonomous Administration is equipped to ensure the fair and transparent allocation of oil products to meet household needs, particularly given the shortcomings of its local governing capacity in other areas.

From the little known about the proposed system at the time of writing, it will likely mirror the unpopular, and often dysfunctional, smart card system implemented in Government of Syria-controlled areas. A growing fear that this system will expand to include other basic commodities such as rice, sugar, tea, and bread has begun to surface on Autonomous Administration-run social media accounts. Notably, the long, tiresome queues continually seen in Government-held areas have been ascribed to the inefficiency of the smart card system. The inability to provide adequate supplies to local vendors in a timely manner, in addition to the severely deficient infrastructure, have made the process of obtaining rations arduous and time-consuming. The population in northeastern Syria now fear that these queues will soon become their reality too.

Lebanese Municipalities Carrying out ‘Census’ of Syrians

Beirut: On 6 July, Lebanese Minister of Social Affairs Ramzi Musharafiyeh delivered a televised address in which he stated that he will visit Syria “soon” to coordinate the return of Syrians from Lebanon. The planned visit comes as a nationwide census of Syrian refugees and guest workers nears completion. Lebanese media report that the census process carried out by municipal councils and governors is 88 percent complete. The process seeks to establish what regions of the country the Syrians came from, with the apparent aim of determining which areas are safe for return. Reportedly, the Government of Syria requested that Lebanese authorities provide more granular detail on the origins of Syrians residing in the country, in order to facilitate their return, although details of the request are not available at the time of writing. The census has indicated that roughly 1.5 million Syrians reside in Lebanon.

Beirut’s bad math

Lebanon has not conducted a nationwide census in nearly a century. The country’s ruling elite have foregone a census at least in part due to the fears that its results will upset the nation’s delicate political and sectarian governing framework. Political considerations are equally important to the so-called census of Syrians in the country. The process is a warning sign that Syrians’ tenuous presence in Lebanon is once again at risk of becoming a mainstay political concern in the country. In the past, deep-seated popular pressure to reduce the presence of Syrians in Lebanon has resulted in documented cases of forced return. Chronically strained services, heightened host-refugee tensions, and concern over aid parity have long been contentious issues in the country. Lebanon’s precipitous economic collapse has only fueled these tensions. Deliberate mismanagement and governmental ineptitude have plunged Lebanon into perilous turmoil; the risk that Syrians will be treated as scapegoats will have grown in parallel. Even if the census does not create an agreement for cooperation with the Government of Syria on refugee return — as has been suggested — it may boost the pressure on Syrians in the country. Observers should beware that risks exist even in the absence of an agreed central government policy concerning return. In the past, local government officials have enacted some of Lebanon’s most onerous restrictions on Syrians, including restrictions on mobility and freedom of movement. Even if forced return does not take place, increased social tensions will be a lasting cause for concern.

Turkey To Allow Syrian Refugees to Spend Eid al-Adha Holiday in Syria

North Rural Aleppo: On 2 and 3 July, the Syrian border crossing authorities of Bab al-Hawa, Bab al-Salameh, Tell Abiad, and Jarablus announced they would allow Syrian refugees in Turkey to visit Syria for the Eid al-Adha holiday. Such visits had been banned for 18 months due to the COVID-19 pandemic. In addition to those with a Temporary Protection Card (Kimlik), the Syrian refugees who are permitted to visit Syria include holders of Short-Term (i.e. touristic) Residency and Work Permits. Notably, Eid holidays are the only times Kimlik-holders are permitted to enter Syria without losing their refugee status in Turkey. Each crossing is equipped with a digital platform where refugees register and are assigned a travel date. The border crossing authorities expect between 90,000 and 100,000 people to return during the holiday. Notably, neither negative PCR tests nor vaccination certificates are required; travellers are merely requested to wear masks and to maintain social distance.

The visits are not limited to Syrians traveling to Turkish-held areas. Those from communities controlled by the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) and the Government of Syria will be also allowed to return, but are required to pass through internal crossing points such as Aoun-al-Dadat crossing. It is still unclear whether people travelling to Government-controlled areas will use crossings in western rural Aleppo (Iss) or southern rural Idleb (Saraqeb).

Turkey encourages “look and see” visits

Allowing Syrians’ temporary return might be one of Turkey’s ‘soft’ tactics to encourage Syrians to return to their hometowns in areas controlled by Turkish-backed armed opposition groups. Turkey currently allows Syrian refugees to remain in their hometowns in Syria for up to six months. As economic conditions improve in Turkish-influenced areas (in marked contrast with Government-held areas), more Syrians may choose to relocate to their hometowns. According to the director of the Bab al-Salameh Crossing, Qasim al-Qasim, 3,000 out of the 35,000 people who crossed into Syria through Bab al-Salameh in 2019 have opted to remain in the country. The dire economic situation and lack of livelihood opportunities in Turkey which is exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic will increase the pressure on other refugees to do the same.

Autonomous Administration Issues Work Cards to Regulate Child Labour

Menbij: In late June, the Autonomous Administration’s Child Protection Office reportedly began issuing work cards for children aged 10 to 18 in Menbij city. The decision may later be extended to include other areas controlled by the Autonomous Administration. Families are required to submit identification documents to confirm the child’s age, the type of work in which they are engaged, and their working hours. On March 24, the Child Protection Office issued a circular specifying the types of labour that children are prohibited from doing because they are dangerous or require great physical exertion.

Curbing child labour is likely out of reach

The Autonomous Administration claims that the work card aims to resolve two issues: rampant child labour and child military recruitment. In early 2021, the NGO Syrians for Truth and Justice documented the recruitment of 19 children by the SDF. Media sources have previously reported incidents of the Autonomous Administration’s Child Protection Office returning children to their families after receiving complaints from families that their children were recruited without their approval or knowledge. The Child Protection Office was established in August 2020, as part of a plan to combat child recruitment agreed upon the previous year by the Commander-in-Chief of the SDF, Mazloum Abdi, and the UN Special Envoy for Syria, Geir Pedersen.

While the work card might be a useful step toward preventing child labour abuse, two important conditions will complicate efforts to prevent child military recruitment. First, despite signing the UN work plan, the SDF has continued to forcibly recruit children under 18 into its ranks. Second, the Child Protection Office has no authority over the SDF or military affairs in general. Steps to enhance child protection should be encouraged; however, without improving the SDF’s transparency and accountability, or ensuring its subordination to the civil authority of the Autonomous Administration, such measures will fall short. Donors working in northeast Syria must approach the new child labour system with extreme caution. Child labour is endemic across Syria, and economic blight has increased the pressure for workforce participation, including among children. Attempts to regulate child labour may succeed in mitigating some abuses inherent to the informal labour market, but they will fail to address the underlying problem.

Ar-Raqqa Regulatory Plan is approved amidst HLP concerns

Ar-Raqqa: On 6 July, the Autonomous Administration’s Local Administrations and Environment Commission approved new planning and development regulations for northern Ar-Raqqa city. Agricultural lands between al-Sawame’ Circle and Hazimeh Circle (aka Area A or the Ba’ath neighborhood), where building was prohibited prior to 2011, were included in the June 2020 regulations issued by the People’s Council of Ar-Raqqa. Since 2020, the Autonomous Administration has made several attempts to implement regulations which would bring buildings up to code in the Ba’ath and Andalus neighbourhoods. For example, on 24 January, the local municipality, backed by units of the Syrian Democratic Forces, carried out demolition campaigns in both neighbourhoods, targeting more than 96 houses. The campaign had previously failed several times due to local resistance that prompted demonstrations. Those whose properties were completely destroyed were compensated with 100 square meter housing units; those who lost portions of their property did not receive any compensation. According to the head of the Urban Planning Bureau in Ar-Raqqa, Shallal al-Najem, there are no plans to change this approach going forward, as “the price of their lands will likely increase following the regulation, offsetting real estate loss.”

Compensation and other concerns

Compensation is often among the most complicated and controversial aspects of regulation. For decades, dozens of families have inhabited the lands located north of the city’s railway, which lie outside of the area covered by the city’s urban planning jurisdiction. Many properties in these areas have been sold by local traders at roughly 10-20 percent of the value of equivalent properties in regulated lands. Ownership and boundaries of such properties are recognised and respected by local residents; however, their unofficial status and lack of building permits make them the most vulnerable to demolition. The truncated properties might be too small to inhabit, and their increased price will not necessarily be enough to provide the liquidity needed to purchase a comparable property elsewhere, driving families to inhabit new informal settlements. Moreover, there are no clear mechanisms for compensating or preserving the property rights of refugees and IDPs who lose their properties during the implementation of the planning and development regulations, which poses another significant Housing, Land, and Property (HLP) concern. Multiple media sources have reported that the Autonomous Administration intends to relocate Kurdish IDPs displaced from Afrin to Ar-Raqqa, which could lead to a major demographic shift in the Arab majority city. Such allegations have been denied by the head of Ar-Raqqa Municipality Ahmad Ibrahim, but the prevalence of such a rumour is itself enough to undermine popular acceptance of the Autonomous Administration.

Open-Source Annex

Key Readings

The Open Source Annex highlights key media reports, research, and primary documents that are not examined in the Syria Update. For a continuously updated collection of such records, searchable by geography, theme, and conflict actor, and curated to meet the needs of decision-makers, please see COAR’s comprehensive online search platform, Alexandrina, at the link below..

Note: These records are solely the responsibility of their creators. COAR does not necessarily endorse — or confirm — the viewpoints expressed by these sources.

What Does it Say? The article details the difficulties faced by people from Dar’a who are migrating to Libya in search of an exit — any exit — from Syria.

Reading Between the Lines: The bridge between Syria and Libya should be seen as a warning sign to Western governments, as it is yet another consequence of a lack of progress to resolve the decade-long protracted crises.

What Does it Say? Syria could lose its textile industry if the cotton harvest is not saved. Syria has imported cotton for the first time in its modern history to avoid this eventuality.

Reading Between the Lines: If steps are not taken to support relevant agriculture, industry, and associated aspects of the value chain cotton may be yet another casualty of the Syria conflict.

How women of Isis in Syrian camps are marrying their way to freedom

What Does it Say? Hundreds of foreign women in al-Hol camp have married people they met online in order to secure a passage out of the camp. Others opt to be smuggled out.

Reading Between the Lines: Western countries have dragged their feet as efforts to repatriate their nationals with IS links have sputtered. Desperate measures to escape squalid camps in northeast Syria are likely to continue.

Syria: People Smugglers Take to TikTok

What Does it Say? TikTok has become a platform smugglers use to advertise. People wanting to escape mandatory conscription can pay 3,000 USD to be smuggled out of Syria. Although the original account advertising escape was banned by TikTok, similar accounts have popped up again.

Reading Between the Lines: The pressure to leave Syria by any means at all is increasing. The use of suck platforms is evidence of the pervasive nature of pressure to leave Syria.

Lebanon’s drug trade booms with help from Hezbollah’s Captagon connection

What Does it Say? Lebanese and Syrian authorities are reportedly trying to stop the Captagon trade on the coastline. Meanwhile, Hezbollah, believed to be facilitating the boom, has maintained plausible deniability.

Reading Between the Lines: In reality, Syrian regime figures benefit from the Captagon trade, as does Hezbollah. Lebanese authorities have neither the power nor the desire to thwart the lucrative drug business.

What Does it Say? A landmine planted by IS was reportedly responsible for a deadly attack on a Government of Syria bus.

Reading Between the Lines: Although IS may no longer have a stronghold in the country, they have ramped up their activity in recent months.