Background

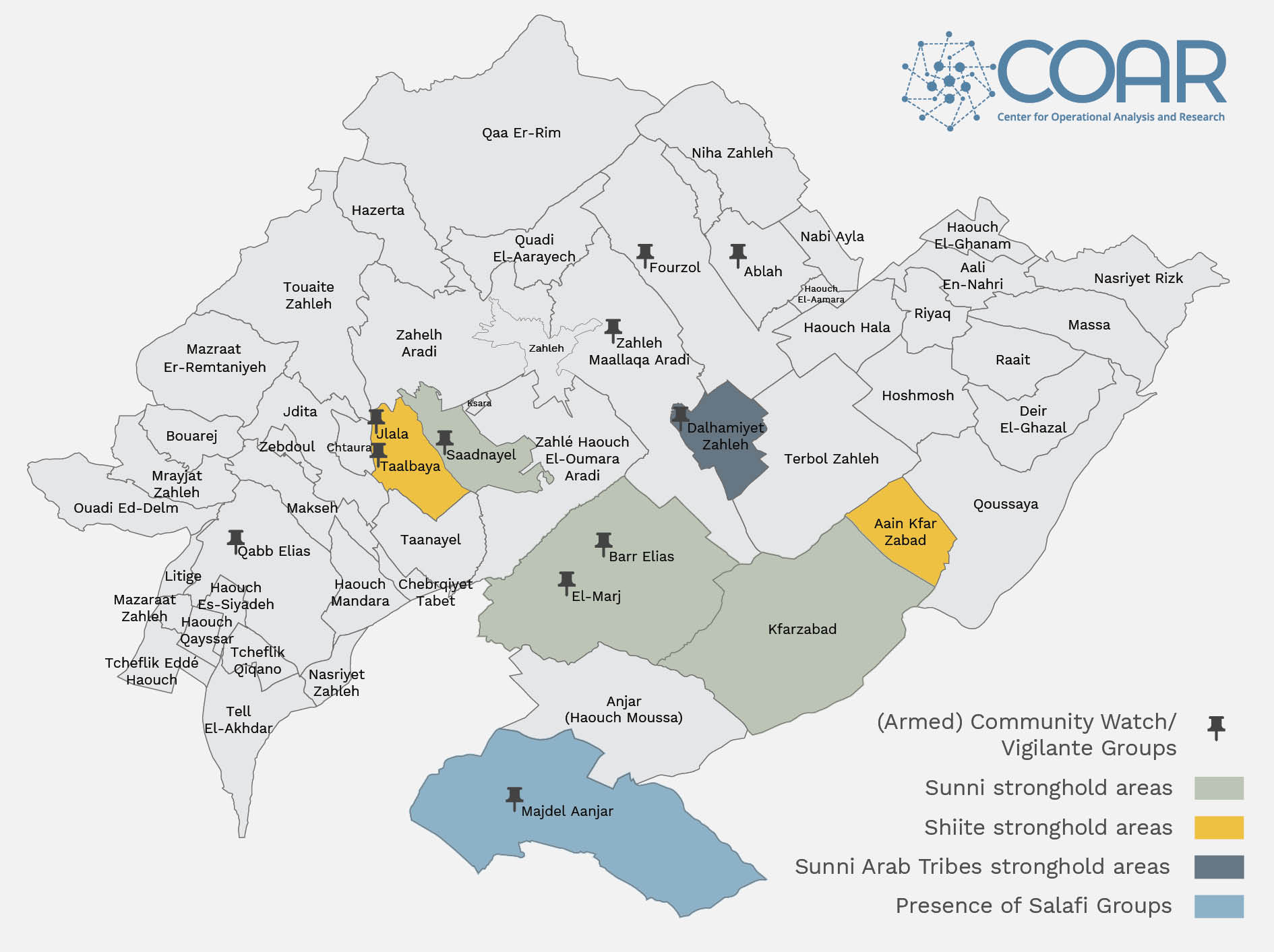

The following section provides a conflict analysis of the region generally known as Central Bekaa, administratively located in Zahle district. Central Bekaa is generally mixed in terms of political affiliation and religious and confessional groups, with Christians, Sunnis, Shiites, and Druze communities. Strong family and clan ties, in all sects, are prevalent and shape conflict dynamics. The area is characterized by economic disparity, with varied levels of wealth — both real and perceived — across society, though this is not a source of tension. Generally, conflict dynamics in Central Bekaa are calmer than other areas, such as the adjacent Baalbek-El Hermel Governorate. However, in recent years, two major sources of unresolved tensions — refugee-host tensions and sectarian tensions (mainly between Sunnis and Shiites) — have been predominant and will dictate the possible unravelling of conflict.

-

Refugee-Host Tensions

Historically, the area was not heavily involved in the sectarian battles of the civil war, which means there is no significant enduring intra-Lebanese antagonism.[1]“The Burden of Scarce Opportunities: The Social Stability Context in Central and West Bekaa,” UNDP, March 2017. Available at: … Continue reading However, the area, specifically Zahle city, was heavily bombarded and besieged during the civil war by the Syrian Armed Forces, then part of the peace-keeping Arab Deterrent Force, aided by some Palestine Liberation Organisation factions. This historic dynamic is crucial, as it left scars on the collective memory of the residents and consequently shaped their relationship to the Syrian refugee population. The Bekaa hosts the largest number of registered Syrian refugees in the country, at 39.2 percent of the total refugee population of Lebanon.[2]Operational Data Portal, UNHCR. Available at: https://data2.unhcr.org/en/situations/syria/location/71 Indeed, tensions in the area between refugee and host community are some of the highest in the country and are seemingly ramping up. The proportion of Bekaa-based Lebanese and Syrians rating the quality of relations as “negative” or “very negative” increased from 40.1 percent in July 2020 to 58.1 percent in December 2020 of Ark & UNDP’s “Regular Perception Surveys on Social Tensions”. A high number of evictions have taken place in the area in recent years, led by municipalities as well as individual landlords.[3]In 2017, more than 7,524 refugees were evicted from settlements near the Ryak Military Airport, while more than 300 families were evicted from Zahle. Other than historical grievances, tensions also emerge from issues related to competition over lower-skilled jobs and livelihoods.

-

Sectarian Tensions – Sunni-Shiite

Politically, and despite recent changes in the allegiance of the national blocs, the scene in Central Bekaa largely mirrors the countrywide March 8/March 14 political division. Traditional political parties have a strong foothold in the area and are deeply entrenched in the different communities, sects, clans, and tribes of the area, to the extent that an activist movement is nearly absent.[4]Only some individual activists were noted in Saadnayel, Bar Elias, Zahle, and Ablah, with very limited influence and a small number of supporters. While political-sectarian dynamics in the area were relatively static in the years that followed the end of the civil war, tensions between Sunnis and Shiites have been mounting since around 2005, when former Prime Minister Rafic Hariri was assassinated and some blamed Hezbollah and the Assad regime. Of note, it is important to understand the general resentment many Sunnis in Lebanon feel toward Hezbollah’s expanding role and influence. Hezbollah’s involvement in the Syrian war in favour of Assad has further heightened tensions. They reached an all-time high in May 2008, when armed clashes took place between the Sunni town of Saadnayel and the adjacent Shiite town of Taalabaya.[5]In May 2008, Hezbollah and affiliated parties launched an offensive on the capital and took over much of West Beirut, following the government’s decision to shut down Hezbollah’s … Continue reading This confrontation dragged on until the following month, bringing in the Sunni town Bar Elias in support of Saadnayel and resulting in at least three fatalities and five injuries. Other tensions have been triggered by kidnapping operations, mainly on the Zahle-Baalbek highway and Ablah-Fourzol road; this has been a frequent cause of tension between Shiites and both Sunnis and Christians.

Stakeholders

The following table lists stakeholders that are crucial to consider in the context of a conflict in Central Bekaa and who have the capacity to either escalate or deescalate conflict levels. The list is not exhaustive and only includes actors with critical or major roles in conflict dynamics.

| Type | Name / Presence /Role | Impact on Programme | Recommendations | |

|

Traditional political parties |

Christians |

Lebanese Forces (LF) – garners the majority of Christian support | Potential spoilers:

|

|

| Free Patriotic Movement (FPM) | ||||

| Kataeb (Phalangists) | ||||

| Sunni | Future Party | |||

| Jamaa’ Islamiyya (a branch of the Muslim Brotherhood) | ||||

|

Shiite |

Hezbollah – garners almost 70 percent of Shiite support | |||

| Amal Movement | ||||

| Lebanese Resistance Brigades (Saraya Mokawame): Made up of non-Shiite strongmen who inform and support Hezbollah in areas where it has little influence. The group is mainly present in Qabb Elias, Bar Elias, and Saadnayel towns. | ||||

| Security institutions | Internal Security Forces | Potential Stabilizers:

Potential Spoilers:

|

|

|

| Lebanese Armed Forces | ||||

| Lebanese Armed Forces – Intelligence Directorate (heavily involved in the general Bekaa Governorate) | ||||

| Municipalities | There is a critical disparity in the role of different municipalities in Central Bekaa.

Zahle’s municipality is the most capable in the area in terms of logistical and human resources, as well as service provision. In contrast, municipalities of adjacent areas suffer from a lack of resources and are considerably less capable of providing services.[6]Two municipalities unions (UoMs) were formed in Central Bekaa: Central Bekaa UOM (7 municipalities: Qabb Elias, Bouarej, Anjar, Majdal Anjar, Bar Elias, Meksi, Mreijat; East Zahle UoM (11 … Continue reading |

Potential Stabilizers:

Potential Spoilers:

|

Engagement, information sharing, project design, coordination for implementation

Mitigate:

|

|

| Nomads | Arab Sunni tribes (known as Al Arab); mainly concentrated in the southern and western part of the area | Potential Stabilizers

Potential Spoilers

|

|

|

| Salafists | The few Salafist groups are concentrated in predominant Sunni areas such as Majdal Anjar, Saadnayel, Bar Elias, and El Marj. Central and West Bekaa are considered the second stronghold of Salafist thought — Tripoli being the first. The Salafists have their own networks of mosques, services provision and sheikhs. Sheikh Adnan Imama is the leader of Salafists in Bekaa and considered the co-founder of the movement in the area, along with Hassan Abed Al Rahman. The movement strengthened its popular support in the area after Hezbollah’s invasion of West Beirut in May 2008 and, later, after Hezbollah’s military involvement in Syria. | Potential Spoilers:

|

|

|

| CSOs & NGOs | Heavily present due to the high number of refugees in the area; the toll that the economic crisis had on the host community has exacerbated their perceptions of the unfair delivery of aid, as they see it as mostly directed to refugees. | Potential Stabilizers: provision of aid, services and other programmes that diffuse tensions and mitigate economic hardships

Potential Spoilers: several local CSOs affiliated with political and/or religious groups >>> politicizing aid |

|

|

Scenarios

1- A Worsened Status Quo

Best-Case Scenario – Most likely

This scenario assumes that the political, economic, social and security situation will worsen in Central Bekaa, however not to the extent of devolving into an open armed conflict. Essentially, the area becomes increasingly affected by the worsening economic crisis, with increased levels of poverty in both refugee and host communities. The gradual lift of subsidies renders hundreds of households unable to afford the most basic items, and they suffer to make ends meet. Governmental and municipal services reach an all time low, with electricity, water, health, waste management, and other services critically impacted. Politically, the area is affected by the charged national atmosphere characterised by an increasing schism between traditional parties, a possible shifting of allegiances, and elevated hostile rhetoric that manifests along sectarian lines. The security situation also mirrors the broader hollowing out of the country’s security services, which will translate into heightened crime rates, proliferation of armed community watch groups and an increase in the frequency and intensity of armed clashes between different groups. The deteriorating situation exacerbates xenophobic rhetoric against Syrian refugees and prompts medium-sized displacements, especially from predominantly Christian areas. However, this scenario presumes that political parties have no appetite for a prolonged armed confrontation and are able to contain tensions and clashes and to pacify their supporters.

Conflict Dynamics

Sunni-Shiite: tensions are heightened as a result of the charged national political atmosphere, especially between Hezbollah and opposing parties such as the Future party, Lebanese Forces, and Kataeb. Clashes between Sunnis and Shiites, mostly armed, take place at least once per month and could be triggered by trivial incidents such as right of way or road blockage. Incidents are expected to take place along the central western part of the area, mainly between the towns of Saadnayel and Bar Elias on one side (Sunnis) and the towns of Taalabaya and Jlala (Shiites) on the other side. This will be considered one of the most volatile fronts of the conflict in this scenario, specifically because of the explicit split of sects between the towns, rendering them community frontlines. The intensity of conflict dynamics is also fueled by the characteristics of these towns. Jlala, for instance, is considered a highly securitised area with the presence of some Shiite clans that have their stronghold in the neighboring Baalbek-Hermel Governorate — such the Zeiater clan. The parents of the notorious drug lord Nouh Zeiater reside in the area. As for the Sunni towns, they will most likely enjoy the support of the Sunni Al Arabs (especially those located in the nearby Dalhamiye and Al Faour areas). Sunni-Shiite clashes are also expected to increase between the towns of Ain Kfar Zabad (Shiite) and Kfar Zabad (Sunni), along the eastern side of the area.

Host-Refugee Tensions: As the economic crisis worsens, Lebanese are becoming more protective of whatever resources are left in the country. Added to this dynamic are the historical grievances, described above, especially those stamped in the memory of Christian communities. As such, hostile acts towards refugee communities are very likely to increase, in this scenario. These include forced evictions (some municipality led), verbal and physical harassment, and denial of access to basic goods (such as fuel and medicines).

Community Policing/Watch Groups: In this scenario, armed community watch groups proliferate to compensate for the decreased capacity of the state’s security apparatus. Indeed, such groups have already formed and been reported in areas including Saadnayel, Jlala, Ablah, Forzoul Maallaka, Majdal Anjar, Bar Elias, El Marj, and Qabb Elias. Given the heavy affluence of traditional political parties in the area, these groups are formed and armed by parties like Hezbollah, the Amal Movement, Future Party, and Lebanese Forces. Al Arab also have long had their own community security groups, and there are Salafist groups in areas such as Majdal Anjar.

Islamic Extremism: The risk of increased Islamic extremism is slightly heightened in this scenario, especially given the dire economic situation and the deep well of conservatism in areas such as in Bar Elias, Qabb Elias, and Saadnayel.

Impact: Refer to the “General impact” section in the national scenario. Note the following specific impact for Central Bekaa:

Medium-sized displacement of Syrian refugees: Displacements are most likely to take place in Christian areas, mainly Zahle and surrounds, as well as Ablah, Fourzol, and Rayak. Refugees are likely to reside in Sunni or Shiite areas, where the environment has been generally more welcoming and sympathetic.

2- Escalating Sunni-Shiite Tensions, Occasional Clashes

Pessimistic – Less Likely

This scenario largely involves the same dynamics as the most likely scenario, but it assumes more frequent and tense clashes between different sects and communities. Tensions are heightened due to two main reasons: Firstly, as the economic situation further deteriorates and plunges the majority of the population into destitution, competition over resources will inevitably increase; this is critical in an area like Central Bekaa due to the multiplicity of sects. Secondly, the local political context will be influenced by the broader national political context, where tensions will reach an all time high, especially between the Sunni and Shiite political blocs. This scenario presumes that these factors will trigger more frequent and intense armed clashes between sects. Kidnapping and hostage-taking will become more prevalent in this scenario. The following conflict dynamics will pertain:

Sunni-Shiite: Armed confrontations are centred along the two aforementioned fronts: the towns of Saadnayel and Bar Elias on one side (Sunni) and those of Taalabaya and Jlala (Shiite) on the other; and Ain Kfar Zabad (Shiite) and Kfar Zabad (Sunni) towns. Armed clashes in this scenario are regular and last for days at a time, with the designated areas considered active frontlines. The Sunnis will receive Al Arab support alongside assistance from Salafist groups, who are expected to gain wider popular Sunni support in the area, especially in Majdal Anjar. Due to the unequal power balance, however, clashes are likely to conclude in favor of the Shiites. Sunnis residing in mixed areas or in places adjacent to Shiite areas are expected to displace to the centre of Sunni stronghold towns.

Other sectarian tensions: This scenario presumes that tensions between other sects will be heightened, albeit to a lesser degree than Sunni-Shiite tensions. These will include Shiite-Christian and intra-Al Arab tribal tensions (see frontlines in the worst-case scenario below).

Community Policing/Watch Groups: Armed watch groups will become more structured and organised, whereby each community might erect checkpoints at its entrance. This will be a source of tension both within areas, especially in mixed communities, and between areas. It is also likely to trigger the displacement of minorities into areas where their sect is more prevalent.

Islamic Extremism: The risk of Islamic extremism increases in this scenario and should be considered a critical dynamic. With Sunnis feeling fragmented and leaderless, and resentment against Hezbollah increasing, many Sunnis will be inclined to lean toward more radical groups for perceived protection; Majdal Anjar becomes a hotbed for such groups.

Impact on Syrian refugees is largely similar to the best-case scenario, albeit with slightly higher numbers of displacements from areas of active conflict.

3- Open Sectarian Armed Conflict

Worst-Case Scenario – Least Likely

In this scenario, Central Bekaa devolves into a wide-scale civil war. This assumption is based on worsening national political-sectarian tensions, with effects reaching into Central Bekaa. Areas are split into homogenous sectarian pockets — starting with Zahle, which becomes an enclave for Christians. Shiites converge in northeastern areas such as Aali en Nahri, Houch El-Ghanam, and Hosh Hala; Sunnis remain in their pockets, mainly central, southern and south-western. Extremist groups are formed and based in several pockets, increasing the risk of asymmetrical attacks. The following conflict dynamics will pertain:

Sunni-Shiite: Same as the aforementioned fronts.

Shiite-Christians: Tensions will manifest along three fronts:

- Central part of Zahle between Al Watani neighborhood (Shiite) and Haouch el Oumara (Christian – LF), and between Karak Nouh (Shiite) and Maallaka (Christian – LF)

- Central-eastern part of the area, mainly within Fourzol and Ablah; both are Christian majority but also have a Shiite presence. Last year, tensions arose during Aashoura, when Shiites put up flags associated with the holiday. Supporters of the Lebanese Forces replaced these flags with the LF flag, resulting in skirmishes between both sides.

- Northern part of the area, between Hazzarta town (Shiite – majority Amal Movement supporters) and Zahle (Christian)

Intra-Al Arab tribal tensions: Tensions will take place where the tribes are concentrated:

- Bar Elias and El Marj (within and between those two towns)

- Qabb Elias

- Al Faour (Al Hrouk tribe is the largest in the town)

- Dalhamiye (Al Lweis and Jarmeish clans are the largest)

Impact on Syrian refugees: The majority of refugees will likely be expelled or voluntarily displaced to avoid active conflict areas. The majority are likely to travel into Baalbek-Hermel Governorate.

References[+]

| ↑1 | “The Burden of Scarce Opportunities: The Social Stability Context in Central and West Bekaa,” UNDP, March 2017. Available at: https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/UNDPCAC%26WBekaa-TheBurdenofScarceOpportunitiesbookletEnglish.pdf |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Operational Data Portal, UNHCR. Available at: https://data2.unhcr.org/en/situations/syria/location/71 |

| ↑3 | In 2017, more than 7,524 refugees were evicted from settlements near the Ryak Military Airport, while more than 300 families were evicted from Zahle. |

| ↑4 | Only some individual activists were noted in Saadnayel, Bar Elias, Zahle, and Ablah, with very limited influence and a small number of supporters. |

| ↑5 | In May 2008, Hezbollah and affiliated parties launched an offensive on the capital and took over much of West Beirut, following the government’s decision to shut down Hezbollah’s telecommunication network and remove the Beirut Airport head of security. |

| ↑6 | Two municipalities unions (UoMs) were formed in Central Bekaa: Central Bekaa UOM (7 municipalities: Qabb Elias, Bouarej, Anjar, Majdal Anjar, Bar Elias, Meksi, Mreijat; East Zahle UoM (11 municipalities: Raeet, Deir Ghazal, Koussaya, Masa, Kfar Zabad, Terbol, Ain Kfar Zabad, Hayy Fekani, Aali en Nahri, Rayak, Hosh Hola, Naseriyye). |