Syria Update Digest

To mark the anniversary of the Syrian uprising, the Syrian Democratic Council (SDC) has shown greater openness to talks with the Syrian opposition than at any point in recent memory. At first glance, such a move makes good political sense. A more united Kurdish-opposition front would strengthen Kurdish negotiations with the Syrian Government, potentially helping fulfill a range of objectives. The developments come in conjunction with several boosts to the Kurdish political movement in the form of rumoured Caesar sanction waivers and Russian sponsorship of Kurdish involvement in the constitutional committee process. It may be that the SDC is therefore emboldened at a time when the attention of the major players in Syria is diverted by events in Eastern Europe. The reality, however, is that the SDC and its affiliates remain as vulnerable to geopolitics as ever. Aid actors would do well to recognise that, while Ukraine has changed a great deal, many of the fundamentals that make for an intractable political situation and an uncertain operating environment are likely to persist both in the northeast and across Syria more broadly.

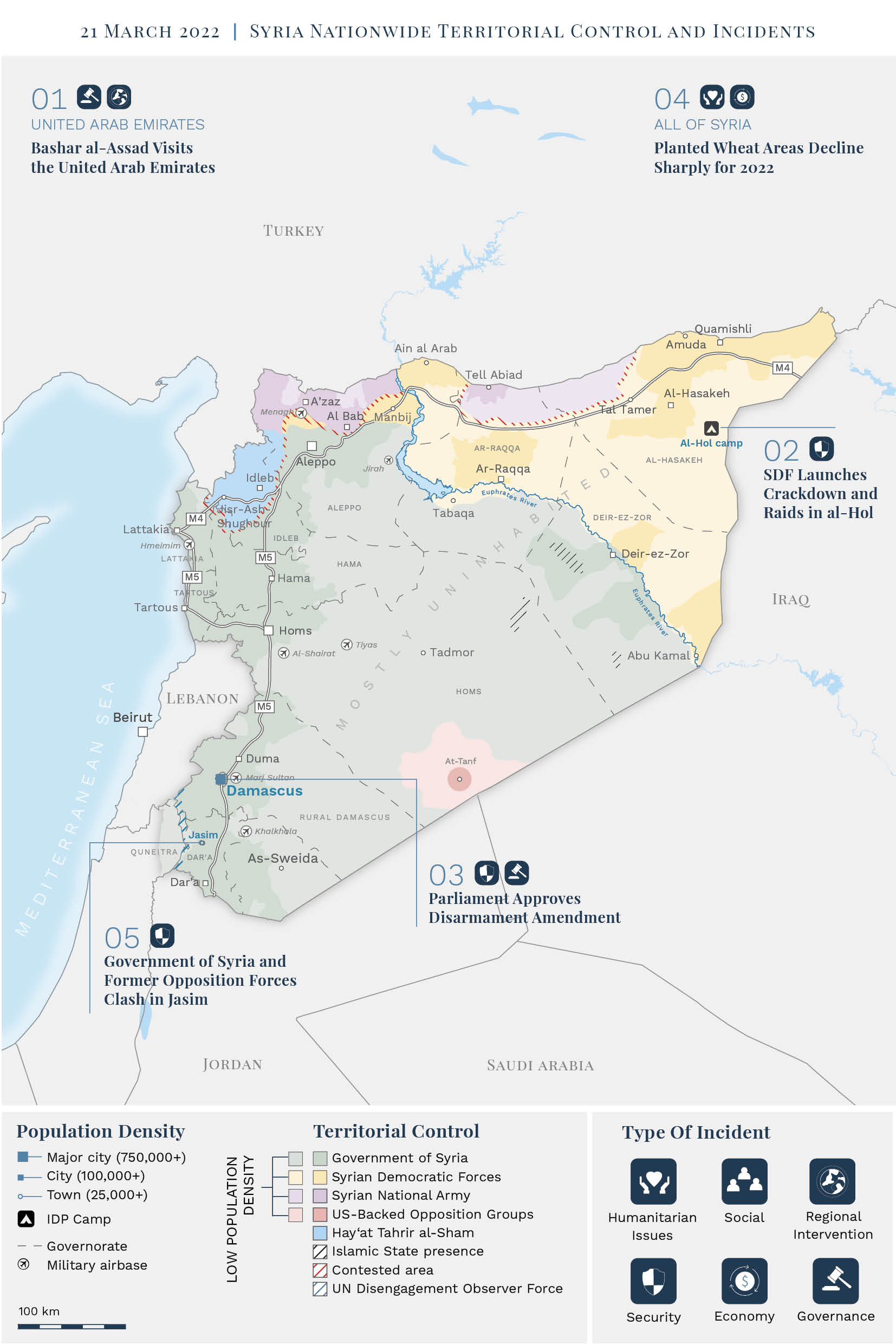

- On 18 March, Syrian President Bashar al-Assad travelled to the United Arab Emirates — his first trip to another Arab state since the outbreak of the war in 2011. The visit is the clearest signal so far of the Arab world’s intention to restore relations with the Government of Syria, with the desire to contain Iran looming large.

- On 13 March, the SDF waged the largest security crackdown on al-Hol camp since the beginning of the year, and claimed to have found weapons, ammunition, and tunnels that IS sleeper cells were planning to use to assume control over the camp. While such an assault would have little strategic value, al-Hol remains a potent symbol and recruitment tool for IS.

- On 28 February, the Syrian People’s Assembly approved an amendment to the 2001 Weapons and Ammunition law which provided a nine-month period in which unlicensed weapons can be turned over to the Government without penalty. While some civilians may hand over their weapons, criminal elements and latent opposition groups are unlikely to readily give them up.

- On 11 March, the Director of Plant Production at the Ministry of Agriculture, Ahmed Haidar, stated that the total area planted with wheat for the upcoming season amounts to 1.2 million hectares, down from 1.5 million in 2021. The decline is a concerning signal that Syria’s wheat production will be historically low in 2022, exacerbating the state of food insecurity in the country.

- On 15 March, violent clashes took place in Jasim, northern Dar’a, between governmental forces and local armed groups. The clashes in Dar’a highlight the still-fragile state of security in southern Syria, and reflect the inefficacy of the Syrian Government and Russia to impose long-term stability in the region.

In-Depth Analysis

The past week has seen several events indicative of a subtle shift in direction for Kurdish-linked armed and political forces in Syria’s northeast. On the military front, and further to recent clashes in Al-Hasakeh Governorate (see: Syria Update 7 March 2022), the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) and Syrian Government forces engaged in minor skirmishes in the SDF-controlled Sheikh Maqsoud neighbourhood in northern Aleppo City. In the political arena, the Syrian Democratic Council (SDC) laid unequivocal blame for Syria’s protracted crisis at the feet of the Syrian Government, expressing hitherto limited sympathy for the Syrian opposition in a statement commemorating the protests which sparked the Syrian uprisings.

Without question, the SDC and its affiliates are increasingly emboldened. The latest events must be seen in the context of month-old rumours of Caesar sanction waivers for SDF- and opposition-controlled areas, the attempts of (predominantly Kurdish) civil society organisations to ensure recognition of the ‘multi-ethnic composition of Syria’s population’ in the Brussels conference, Russian sponsorship of Kurdish participation in the constitutional committee process, and the continued intractability of SDC-Syrian Government economic and political negotiations. Whether the SDC’s changing posture results from fewer concerns over military pressure from Turkey, decreased direct Russian support to the Syrian Government, or further confidence over the US’s foreign military presence subsequent to the war in Ukraine is unclear. However, the prospect of more assertive Kurdish conduct must not be overstated in the context of these events. International diplomacy affecting parties with a stake in both Syria and Ukraine is more uncertain, but it has yet to presage any change that lends substantive support to Kurdish autonomy. Small changes, including growing space for inter-party dialogue, are decidedly possible, yet many of the fundamentals that make for an intractable political situation and an uncertain operating environment in Syria are likely to persist.

Change of tack for the SDC?

The SDC’s openness to the Syrian opposition is not a novel development in itself. The SDC has organised an annual event with opposition counterparts since 2018 and sent a delegation to a parallel process facilitated by the Olof Palme Centre in late 2021. However, the SDC’s recent statement is arguably the strongest signal so far that it intends to court the Syrian opposition beyond mutual points of interest on democracy, displacement, and detainees, and potentially with a view to approaching some of its outstanding issues with Turkey and Turkish-backed armed groups in Syria’s north and northwest.

Chief among these issues will be the security of SDF-controlled areas, but other points of friction such as transboundary water flows and demographic change wrought by Turkish-led military intervention could also feature. Talks with the opposition might also be conceived as a means to alleviate some of the pressure experienced by Kurdish-linked authorities in Arab-majority communities throughout the northeast. Longer term, the SDC’s rapprochement with the opposition could be calibrated to present a more united front in discussions with the Syrian Government, pushing Damascus into progressing the political process, and enforcing more preferable concessions. Were these amongst the SDC’s objectives, they would signal a concerted attempt to wrestle back control from the international deference and dependency which has typically defined its negotiating position to date. However, any such political alignment will be impeded by persistent friction on military and security affairs between the SDF and its opposition counterparts, as the parties have often hit a dead end over their own legacy of confrontation, to say nothing of Turkey’s concern over the build-up on its southern border of Kurdish forces it views as a profound national security threat.

Continued Kurdish vulnerability

Speculation is natural in the current geopolitical climate. Russian intervention in Ukraine has loosened several of the screws that have upheld the Syrian status quo, presenting all actors with an array of options and opportunities. For the time being, however, events in Eastern Europe have yet to produce knock-on effects that have fundamentally altered the military or political trajectory of the Syrian crisis in ways that were unforeseeable late last year. Rather, Russia’s invasion has created space for more posturing and prevarication without removing any of the pre-existing barriers to a real political solution. Neither has it fundamentally decreased the vulnerability of territories under the control of the SDF and the majority-political influence of the SDC.

Regardless of events in Ukraine, the prospect of greater Kurdish autonomy remains unpalatable for the Syrian Government. Indeed, deeper collaboration between the SDC and the Syrian opposition is only likely to prompt Damascus to destabilise the northeast in an attempt to recover the region’s natural resources and nationwide political-military control. Meanwhile, Turkish relations with Russia are even more delicately poised subsequent to the war in Ukraine, meaning neither party is likely to tip the balance in Syria until more predictability is introduced into Eastern Europe. Any fundamental shift in Turkey’s Syria policy is also assessed as unlikely until the conclusion of the Turkish general elections next year, although political calculations may prompt changes of course and sharper rhetoric.

Certainly, Western opposition to Russian intervention in Ukraine will compel the US to retain its presence in northeast Syria as a point of leverage, but the reality is that the SDC and its affiliates are in no stronger position today than they have been for several years. In all likelihood, SDC-opposition talks will be piecemeal in consequence, rolled back where they overstep lines drawn by the major powers, and held at the margins of processes that are likely to determine Syria’s future. While it may help achieve minor political victories, Kurdish manoeuvring is therefore largely peripheral. For aid actors with a stake in Syria’s recovery, it is also a reminder that while much may have changed as a result of the war in Ukraine, many of the fundamentals that make for an intractable political situation and an uncertain operating environment are likely to persist both in the northeast and across Syria more broadly.

Whole of Syria Review

Bashar al-Assad Visits the United Arab Emirates

On 18 March, Syrian President Bashar al-Assad travelled to the United Arab Emirates — his first trip to another Arab state since the outbreak of the war in 2011 — and met with Crown Prince Mohammed bin Zayed, as well as with the ruler of Dubai, Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid al-Maktoum. They discussed the need to preserve the territorial integrity of Syria and for the withdrawal of foreign forces, as well as the possibility of the UAE providing political and humanitarian support to Syria. The US State Department said Washington was “profoundly disappointed” at the “apparent attempt to legitimise Bashar al-Assad.”

All eyes on Iran

The visit is the clearest signal so far of the intention in some corners of the Arab world to restore relations with the Government of Syria, and indeed to countenance the rehabilitation of Bashar al-Assad. The UAE has been among the most forthright of the Arab states in seeking normalisation with Damascus, reopening its embassy in 2018, and sending its foreign minister for a high-level meeting in November 2021 (see: Syria Update 15 November 2021). Despite signs last year that regional rapprochement with Syria was gaining momentum (see: Syria Update 11 October 2021), such efforts appeared to have stalled. Jordan, among the most ambitious advocates of closer functional relations with Damascus, has reined in its efforts, which have faltered amid an increase in drugs-related border violence. Syria’s ready support for Russia in its invasion of Ukraine will only have made such rapprochement more challenging (see: Crisis in Ukraine: Impacts for Syria). Looming large in the UAE’s push is its desire to contain Iranian influence, particularly as negotiations appear to be close to seeing Iran return to the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) nuclear deal, providing sanctions relief that could facilitate increased support for regional paramilitary activity and heightened investment in Syria’s reconstruction. To succeed in containment, however, the UAE would need to compete with investments to wean Damascus from Iranian support — requiring navigating US sanctions that show little sign of being lifted any time soon. Western donor governments should take note. There is a growing need to communicate to regional partners, the general public, and Syrians themselves that efforts to alleviate the suffering of the Syrian population are just that — and not a bid for engagement with al-Assad.

SDF Launches Crackdown and Raids in al-Hol

On 13 March, the SDF and its internal security forces (Asayish), in coordination with the International Coalition, waged the largest security crackdown since the start of the year in al-Hol camp, which houses tens of thousands of women and children with perceived Islamic State (IS) affiliation. The camp’s security forces found weapons, ammunition, and tunnels that they claimed IS sleeper cells inside the camp had been planning to use in a large-scale attack aimed at establishing control over al-Hol. The crackdown came three days after IS named Abu al-Hassan al-Hashimi al-Qurayshi as its new leader, succeeding Abu Ibrahim al-Hashimi al-Qurayshi, who was killed during a US military operation in Idleb in February (see: Syria Update 7 February 2022).

IS is still a threat, but crackdowns are routine

The SDF’s security crackdowns on al-Hol are routine (see: Syria Update 14 February 2022), and may have little to do with alleged plans by IS to seize control of the camp. Nevertheless, the recent al-Sina’a prison attack in Al-Hasakeh City (see: Syria Update: 31 January 2022) served as a reminder that the group can disrupt regional stability amid the SDF’s limited capacity to deal with such threats. IS’s new leader may seek to boost his group’s morale and demonstrate his commitment to those in al-Hol — a theme that dominates the IS propaganda machine — by preparing a new large-scale attack. Al-Hol remains a potent recruiting tool for IS, and children there are particularly susceptible to radicalisation. However, while symbolic, such an attack would provide little strategic or military value, given al-Hol mainly houses women and children, unlike the attack on al-Sina’a, which sought to free captured fighters. Durable solutions are needed to ensure women and children are able to leave the camp and reintegrate into wider society (see: Mapping and Assessing Release and Reintegration Models from NE Syria Camps), while broader stabilisation and livelihood initiatives across northeast Syria should be used to address local grievances and reduce the attractiveness of IS recruiting propaganda (see: Countering Violent Extremism and Deradicalisation in Northeast Syria).

Parliament Approves Disarmament Amendment

On 28 February, the Syrian parliament approved an amendment to the 2001 Weapons and Ammunition law, targeting weapons manufacturers, smugglers, and civilians who possess weaponry. The provisions include a nine-month period in which unlicensed and “non-licensable” military weapons or ammunition, such as explosives, can be turned over to the Government without penalty. Holders of unlicensed weapons can also apply for a licence within the period to avoid penalty. The weapons law was previously amended in 2017 to raise the cost of licences.

Twisting arms to disarm

While a small number of civilians may relinquish their weapons or apply for licences under the new amnesty, broader compliance is unlikely. Ordinary Syrians have abundant reason to retain some capacity for self-defence, while criminal elements and latent opposition groups with large weapons caches are unlikely to readily give them up. Previous attempts to disarm reconciled opposition groups sparked the Dar’a siege, one of the largest outbreaks of violence in the region in years (see: Syria Update 5 July 2021). Accurate data on weapons ownership is unavailable in Syria, though one estimate suggested gun ownership doubled between 2007 and 2017. The conflict-driven prevalence of small arms in Syria poses a threat to the Government of Syria’s monopoly of force and facilitates widespread criminality, particularly in southern Syria. With the Government unable or unwilling to provide effective law enforcement in As-Sweida, for example, the widespread availability of weapons has underpinned a rise in crimes such as kidnapping and drug trafficking (see: Syria Update 31 January 2022). While it is unclear what immediate impact the change in the law would have, it may herald a future clampdown on weapons ownership, a key step in disarmament and demobilisation following the violence of the past 11 years. A further step — reintegration of former fighters into a functional, sustainable national economy — is more distant still.

Planted Wheat Areas Decline Sharply for 2022

On 11 March, the Director of Plant Production at the Ministry of Agriculture, Ahmed Haidar, gave a radio interview in which he stated that the total area planted with wheat for the upcoming season amounts to 1.2 million hectares, down from 1.5 million in 2021. The decline is largely due to a reduction in rainfed cultivated areas, precipitated by delayed rainfall. The Syrian Farmers Union also expressed fears that limited rainfall and the lack of diesel to fuel irrigation systems impact this year’s harvest. In defiance of the well-documented reality (see: Syria Update 10 January 2022), Syrian Prime Minister Hussein Arnous claimed on 14 March that the country had sufficient wheat to tide it over until the next harvest season. The statement, which contradicted multiple international studies and reports, was dismissed by opposition news sources.

Neither sowing nor reaping

The decline in planted wheat augurs historically paltry wheat production in 2022, exacerbating food insecurity. Syria harvested just over half of its planted wheat last season (following the 2021 drought), compared to almost all of the 1.35 million hectares planted in the previous season. Even if all 1.2 million hectares are successfully harvested in the coming season, this would mark a decline from 2019-2020, and likely necessitate significant imports to keep Syrians fed. Despite Arnous’s claims to the contrary, Syria struggled to import necessary foodstuffs and commodities even before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine (see: Syria Update 7 March 2022), which has driven the global market price of wheat to its highest level since 2008, and now poses a risk to all wheat importers, not only the Arab and African states that rely heavily on Black Sea imports. The prospect of an enduring wheat crisis highlights the need for aid actors to focus on building resilience in the Syrian agricultural sector, particularly in supporting the infrastructure needed to ensure that planted crops are harvested.

Government of Syria and Former Opposition Forces Clash in Jasim

On 15 March, violent clashes broke out in Jasim, northern Dar’a Governorate, between local armed groups and Government forces when the latter launched raids to arrest fighters who had not participated in reconciliation agreements. One civilian and one Government security officer were reportedly killed, and several pro-Government fighters were injured and arrested by the local armed fighters. Mediation conducted by the Fifth Corps’s 8th Brigade ended the clashes and led to the release of the Government fighters. In a possibly related attack, on 17 March, Jasim municipal council chairman Tayser Aqla was assassinated by unknown assailants. In parallel, demonstrators conducted anti-Government protests in Tafas, Busra al-Sham, and Dar’a al-Balad, in southern Dar’a Governorate, to mark the anniversary of the revolution.

Dar’a remains on a hair trigger

Recent clashes in Dar’a reflect the inability of the Syrian Government and its Russian guarantor to impose long-term stability in southern Syria. Although the situation in Dar’a has remained relatively stable since the military escalation in summer 2021 (see: Syria Update 2 August 2021), which culminated with a new settlement agreement (see: Syria Update 20 September 2021 and Syria Update 11 November 2021), continuing security incidents and assassinations are a strong indicator of the risk of future escalation (see: Syria Update 28 February 2022). In a bid to empower Damascus (see: Syria Update 5 July 2021), Russia has gradually reduced its role as a mediator in the region (see: Syria Update 19 October 2021). However, there remains a significant trust deficit between the Syrian Government and local communities. The agreement reached in Jasim has so far prevented the region from engaging in full-fledged military operations, indicating that local actors do not wish to further destabilise the city or wider region. However, it has not eliminated eruptions of violence with the potential to rapidly escalate. Aid actors contemplating interventions in the area must understand that southern Syria’s relative independence from Damascus authorities — a boon for principled implementation — cuts both ways, and increases the risk that security dynamics will be upended.

Key Readings

The Open Source Annex highlights key media reports, research, and primary documents that are not examined in the Syria Update. For a continuously updated collection of such records, searchable by geography, theme, and conflict actor, and curated to meet the needs of decision-makers, please see COAR’s comprehensive online search platform, Alexandrina, at the link below..

Note: These records are solely the responsibility of their creators. COAR does not necessarily endorse — or confirm — the viewpoints expressed by these sources.

Freeze and Build: A Strategic Approach to Syria Policy

What does it say? The report argues that Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the subsequent collapse of US and European diplomatic relations with Moscow have rendered Syria diplomacy all but dead. To respond to this new context, it suggests a fundamental shift in strategy, prioritising the freezing of combat lines and a more strategic deployment of aid, stability, and ‘targeted reconstruction’ in areas outside of al-Assad’s control.

Reading between the lines: A transition beyond emergency humanitarian relief is urgently needed in Syria, yet donor agencies and the UN must also prioritise efforts to ensure that civilians in Government-held areas — an outright majority of those in the country — are not left behind. While ‘targeted reconstruction’ is difficult to imagine in such areas in the current political climate, non-emergency aid modalities would offer greater safeguards and mitigations for assistance to these areas.

What does it say? The piece argues that if Russia maintains its current posture in the long term, the Ukraine invasion will push many countries in the Middle East, the Mediterranean, and Africa to rethink a slew of policies, potentially causing major realignments.

Reading between the lines: Values-based cooperation and agreements will be challenged as more countries are asked to pick sides on the global arena. Driven by domestic and regional considerations over food security, trade, energy supplies, arms procurement, and military alliances, countries in the Global South could be pushed to choose between political alignment with Russia and good relations with the West.

Ukraine war stirs fears Russia could weaponize Syria aid

What does it say? As Russia wages war in Ukraine, concerns are mounting that Moscow will use its UN Security Council veto powers to dismantle what remains of cross-border aid operations into Syria.

Reading between the lines: Already imperilled before the invasion, cross-border aid delivery is essential in preventing a humanitarian catastrophe in northwest Syria. Instability resulting from its end could quickly escalate into open conflict along currently frozen frontlines and drive the displacement of millions.

Property Rights in Syria from a Gender Perspective

What does it say? The conflict has forced half the population to leave their homes, sometimes without identification papers and title deeds. Research has shown that myriad obstructing factors have rendered housing and property rights in Syria more complicated for women than men.

Reading between the lines: Depriving women of their property and housing rights is both a symptom and a cause of their low levels of economic empowerment. A gendered approach to HLP rights should be included in all discussions regarding political, legal, social, and transitional justice.

Syrians “Gifting” Their Real Estate to Evade Real Estate Sales Law

What does it say? Damascus residents are using “giveaway laws” to sell their property to avoid engaging in costly and paper-intensive procedures included under Law No. 15, issued in 2021.

Reading between the lines: Taxes, paperwork, freezing of capital, and the high cost of real estate sale services are encouraging residents to use “giveaway contracts,” which allow them to settle transactions based on unofficial agreements that circumvent Government requirements.

The Syrian-Iranian bet and the Russian “knot”

What does it say? Tehran and Damascus hoped that Moscow’s preoccupation with Ukraine would grant the former leeway to solidify its control in Syria and the latter to negotiate with Tehran. Hurdles planted by Moscow to prevent the finalisation of the JCPOA could dash those hopes.

Reading between the lines: The flow of Iranian funds hoped for by both Damascus and Tehran is now subject to approval from Russia. Fearing the loss of a major ally in Tehran with the JCPOA agreement potentially pushing it West, Moscow will seek guarantees to protect its influence and interests in the region.

Brief on the Conditions of Refugees Detained in Lebanon: Unfair Trials, Torture, and Ill-treatment

What does it say? Arbitrary arrest and detention are some of the most prominent violations Syrians are subjected to in Lebanon. The report documents cases of violation at each level of engagement with the judicial system, from arrest to interrogation, trial, and prison conditions.

Reading between the lines: The credibility of Lebanon’s judiciary is further weakened by cases of arbitrary arrest and detention of Syrian refugees.

23,000 Narcotic Pills Seized in Paintings in Damascus

What does it say? The Government’s anti-narcotics security branch seized more than 23,000 Captagon pills hidden inside paintings in the Qadam neighbourhood, south of Damascus city, intended for smuggling.

Reading between the lines: Such seizures by the Syrian Government likely aim to broadcast Damascus’s anti-drug efforts to its neighbours and the world, rather than address the root drivers of the expanding drug trafficking and manufacturing sector.

Russian Military Patrols Syria’s Golan Heights

What does it say? Russian media published a video of Russian military units patrolling the Syrian side of the Golan Heights, which have been occupied by Israel since 1967.

Reading between the lines: The video is likely intended as a reminder of Russia’s role as a guarantor of security in the region, and of the complicated relationship between Russia and major Western allies.