Executive Summary and Methodology

In COAR Global’s first public report on the war in Ukraine, we provide an update on the situation facing civilians in Kyiv. Many longtime observers of Russian warfare fear Ukraine’s capital will be subject to the same siege tactics used against cities like Grozny, Aleppo, and Mariupol. We assess that while a Russian siege of Kyiv is not imminent, aid actors must act immediately to prepare for the possibility. Aid strategies, furthermore, must take into account the nature of the belligerents: Ukraine’s authorities and military are scrambling to meet their citizens’ humanitarian needs, while Russia is instrumentalizing aid as a bargaining chip in its efforts to stamp out Ukraine’s sovereignty and pacify its population. Responders should therefore seek to provide principled aid, rather than adhere strictly to principles of neutrality. To this end, responders should focus on supporting Ukrainian civilian authorities as well as civil society organizations. The goal should be to strengthen Ukraine’s societal resilience, the surest path to a stable humanitarian situation in the long run.

Information for this piece was collected via a mix of open-source research and analysis and informal interviews with key informants currently in Kyiv. The below reflects impressions of a rapidly evolving situation and may no longer hold true as the situation evolves. As this piece is based on a small sample size of 15 respondents, the observations found here should not be assumed as representative but indicative.

Introduction

Four weeks into Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the capital, Kyiv, is threatened by Russian forces. While the current humanitarian situation in Kyiv remains fragile, needs are steadily rising and could escalate rapidly if the speed and severity of the Russian advance intensifies. Aid actors must therefore act now to form coordinated response plans, policy objectives, and theories of change to guide their response both in Kyiv and throughout Ukraine.

Aid actors’ strategies should take into account the specific nature of the belligerents, and their relationships to would-be beneficiaries. The overwhelming majority of people in need are Ukrainian citizens, and Ukrainian official bodies and branches of the armed forces are largely responsible for guaranteeing their access to aid. Russia, meanwhile, has instrumentalized aid as a costly political bargaining chip – in this conflict and in others. The international aid response should therefore be integrated into Ukrainian and international political, diplomatic, and military efforts. The goal should be to strengthen Ukrainian national and local resilience so that the country as a whole, and Kyiv in particular, may weather the invasion, and emerge positioned for a strong recovery.

Thus, while it is still difficult to determine the precise dimensions of support that should be provided, there are some clear conceptual challenges that aid actors must begin to confront. Chief among them is the need to recognize the implications of coordination via the Ukrainian authorities and Ukrainian civil society, both for the application of humanitarian principles in Ukraine and other conflict-affected settings where the bulk of global assistance is mobilized in solidarity with a belligerent party. Donor red lines, policies, and programmes in Ukraine must be designed with these potential implications in mind, focusing on the ways in which they will harness, complement, and enable local capacity in principled service of humanitarian effectiveness. Whether in relation to ongoing evacuation and resupply efforts, or to more diverse humanitarian support, the response in Kyiv must be embedded in an effectiveness-oriented agenda that aligns with appropriate parameters for principled aid.

Key Takeaways

While detailed analysis and specific recommendations for the aid community are beyond the scope of this situation report, there are three key takeaways.

- The mobilization of Western aid in solidarity with Ukraine will give rise to questions about the application of humanitarian principles which could resonate in Ukraine and beyond. Humanitarian neutrality principles should not be strictly applied here, in order for the aid to be effective.

- The situation in Kyiv is fragile. The potential for a rapid and catastrophic deterioration in the face of increased bombardment and/or siege means it is imperative that the aid community support Ukrainian authorities and civil society in their ongoing evacuation and resupply efforts.

- Local Ukrainian civil society-based aid groups and networks are at the center of the humanitarian response. International actors must not supplant or duplicate their work but instead complement local efforts through carefully planned engagement and support.

Kyiv Situation Overview

Russian progress since the 24 February 2022 invasion has been slowed or stalled by the combination of stiff Ukrainian resistance and poor operational execution on most fronts except the south. While the Russian advance on Kyiv appears to have been halted for the time being, Kyiv is under direct threat from large concentrations of Russian forces which, with their maneuver stopped, may increasingly resort to reliance on firepower against the city. This raises the possibility that Russian forces will use similar tactics to reduce Kyiv as in Grozny during the Second Chechen War (1999-2000) and Aleppo in the Syrian Civil War (2016). This would have terrible consequences for civilians in the city.

MILITARY SITUATION

A Russian siege of Kyiv is unlikely in the immediate future, but aid actors should prepare now for the possibility.

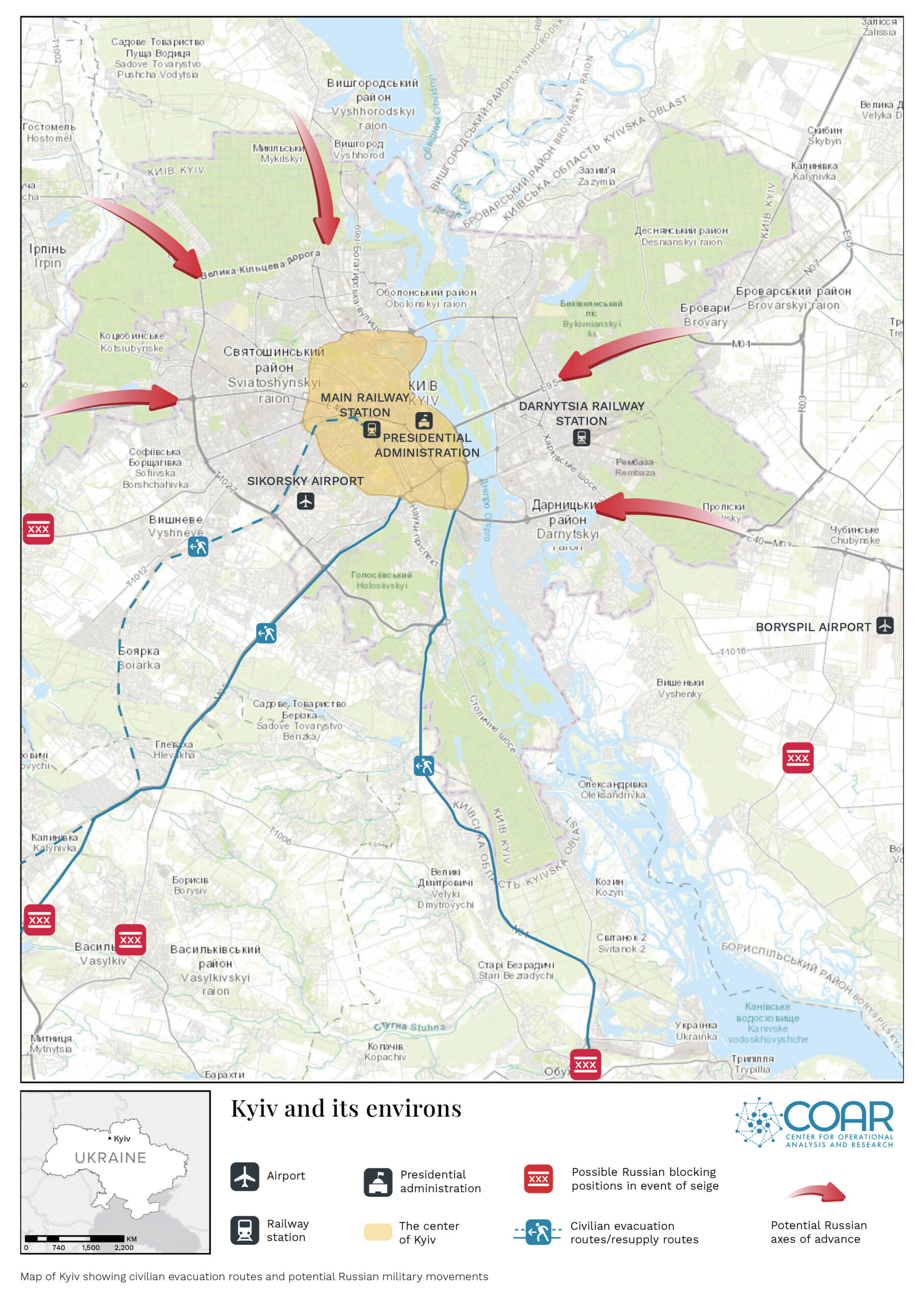

As of 23 March 2022, open-source reporting gives conflicting information on Russian troop locations but indicates the forward line may be as little as 8 km west of the M07 ring road on the west (right) bank of the Dnipro river, and approximately 20 km straight line distance from Kyiv’s city center. On the east (left) bank of the Dnipro, recent fighting has centered on Brovary, about 10 km east of Kyiv’s border. There are three potential Russian courses of action vis-a- vis Kyiv: a frontal attack from the northwest and/or east, envelopment and siege, or a shift to defensive operations and consolidation of territorial gains around Kyiv while the main effort shifts to other fronts, resulting in a stalemate near Kyiv. Currently, open-source reporting on Russian movements suggests that Russian forces are taking the third course of action, and thus, it is assessed to be unlikely that conditions will be set for a siege of Kyiv in the immediate future; however, reporting is uncertain and the situation could change rapidly. International aid actors must prepare immediately.

GEOGRAPHY

Outlying parts of the city are especially vulnerable to siege.

Kyiv is spread out on both sides of the Dnipro river, occupying some 800 square kilometers. West of the river, the ‘right bank’ comprises much of the city center, whereas the east, the ‘left bank,’ consists mainly of densely populated high and low rise residential districts. The city is surrounded by self-contained suburbs, separated from the city and one another by fields and forests. Nine major roads enter the city’s west, while a large number of smaller routes, especially to the south, each join an outer ring road which sits between 9 and 12 km from the city center. The northwest of the city is fronted by forests while the southwest extends into densely populated suburbs, eventually transitioning to farmland. The smaller left bank is accessed by two major east-west highways and a number of roads.

A few trends are clear with regard to the ways in which different parts of the city are affected by conflict. Civilians in the disconnected suburbs are at high risk from a Russian ground advance, as are those in the many large apartment blocks facing main roads, including on the right bank. The city center, with its narrow streets and shorter sight-lines, may be safer for remaining civilians. The left bank is also vulnerable to siege, with only two major routes out of the city to the east and northeast. Most of the bridges connecting the left and right banks are access-controlled by Ukrainian troops, posing significant logistical problems for the evacuation of residents on the eastern side of the river.

DEMOGRAPHICS

Those remaining in the city include many elderly and disabled people.

Despite evacuations, large numbers of people remain in the city among which vulnerable groups are overrepresented. While the city had an official pre-war population of 2.8 million, it is widely believed to have been much higher given much of the population had not registered with city authorities. Mayor Vitali Klichko stated 10 March that while about half the population had already fled, approximately 2 million residents remained (thereby implying a peacetime population of at least 4 million). The elderly (particularly elderly women), people of limited means, people without private transport, the developmentally disabled, and people with limited physical mobility are reportedly represented disproportionately among the remaining population. While women outnumber men in Kyiv, women and children are much more likely to have evacuated, leaving men behind to fight or safeguard family property.

Immediate and Emerging Aid Response Issues

KINETIC THREATS

Sporadic artillery and rocket strikes could foreshadow much worse attacks.

While Kyiv has seen numerous rocket and artillery strikes in residential areas, it has not experienced anything near the full firepower arrayed against it. Multiple attempted infiltrations by Russian reconnaissance elements and saboteurs on both sides of the river have resulted in frequent clashes. To date however, Kyiv’s suburbs and specific ‘military’ targets scattered throughout the city have borne the brunt of Russian shelling and missile strikes.

EVACUATION AND MOBILITY

Evacuation, by any means, is a dangerous undertaking, with residents of Kyiv’s left bank facing particular risks.

While voluntary evacuation trains have been organized and are running regularly, no systematic evacuation of civilians from Kyiv is yet underway. According to UNHCR, over 3 million people have left Ukraine as of 20 March. The number to have left Kyiv is unclear, however. Mayor Klichko has stated that half the city’s population has fled. Taken together with his statement that 2 million remain, this would imply that up to two million individuals may have left the city.

Those still hoping to evacuate face considerable obstacles, especially those on the left bank of the Dnipro river. The metro still runs partially on the right bank but does not cross the river, while the frequent closure of bridges means left bank residents have trouble reaching the main railway station on the right bank. Left bank residents generally need to find a way to cross the river before leaving by road as well, given that the safest routes out are to the south-west. This is particularly challenging for people whose physical mobility is limited. Evacuating by road is dangerous, moreover, as Russian troops have targeted highways with heavy weaponry. Armed Ukrainian territorial defense checkpoints also present the risk of escalation-of-force incidents or abuse of power (eg bribery, robbery and/or criminal violence). These factors have driven up demand for train travel, contributing to crowding at the central station.

FOOD, MEDICAL SUPPLIES AND OTHER COMMODITIES

While most people in Kyiv can still access basic foods and medicines, some elderly and disabled residents, as well as those who have recently lost their source of income, may already face a degree of food insecurity. Their conditions will likely worsen as combat persists.

Reports indicate much of Kyiv’s remaining population can still access staple foods and medicines, although their acquisition may require more patience, exertion, and risk than in peacetime. Some residents report that key items like flour, bread, potatoes, milk, eggs, grains, and meats are all available, yet others report a deficit of flour, sugar, and grains, as well as fruits and vegetables. Finding what one needs may require visiting several different supermarkets, and sometimes waiting in lines for hours. Several interlocutors in Kyiv noted that one needed to be on constant alert for deliveries of key goods. As one left bank resident said, “When something gets delivered to a shop around us, a queue immediately builds up, and sweeps away the whole supply in an hour or two.” Here it should be noted that traveling the city to shop, and/or standing in queues can render one vulnerable to aerial attack: a series of probable Russian airstrikes in Chernihiv on 3 March killed dozens of civilians, including some lining up to buy bread. High-casualty incidents in other conflicts, such as Syria, have also involved people queueing to buy food.

The picture with access to medicine is similar: “There are huge queues, in which you can spend up to four hours,” a 73 year-old resident of the city center reported. “And there’s no guarantee the medicines you need will be available.” Less-specialized medicines, such as anti-inflammatories, fever-reducers, painkillers, hypertension drugs, and common antibiotics like amoxicillin are fairly readily obtainable, yet drugs for serious conditions are in shorter supply and less accessible, most notably insulin, thyroid medications, and some cancer treatments. As a result, doctors have taken to writing Facebook posts explaining, for example, how to lower one’s thyroxine dosage in order to stretch out pill supplies, and discussing possible complications arising from the cessation of medication. Residents also report growing demand for medicines to treat respiratory complaints arising from days and nights spent in bomb shelters.

While these conditions may not put able-bodied residents at immediate risk of hunger or life-threatening illness, they pose greater risks for the disabled and elderly. Locals have organized deliveries of milk and bread to residential courtyards to help feed these vulnerable groups, but it is unclear how systematic these efforts are. The degree to which these initiatives also involve the delivery of medicines is unclear. Aid providers should therefore keep the elderly and disabled in focus even in the event that a siege does not occur. It may also be useful to gather data regarding timing of airstrikes and shelling to help inform civilians of the times of highest risk, so that they can plan their errands accordingly.

Even if the relatively stable status quo holds, the ongoing loss of livelihoods will render more of Kyiv’s remaining residents vulnerable to food insecurity and/or ill health. No data is yet available on the number of businesses that have closed due to the disruptions of combat and displacement, but anecdotal evidence suggests it is high. Some coffee shops and salons have re-opened on a limited basis but service increasingly limited demand – while their former competitors remain shut, leaving masses unemployed. A resident who had previously consulted for a local law firm lost this source of income when hostilities began, as both his employers and clients had left the country. He has since sought work at a grocery store, and said, “I barely have money for food right now.” The number of people in similar positions will surely increase if current levels of kinetic activity and displacement persist.

If Kyiv is besieged, many more will obviously be at risk. According to municipal authorities, the city has a two-week supply of essential foods for its two million remaining residents. Given that a potential siege could last much longer – for example, Mariupol, as of writing, has been blockaded for nearly three weeks – the city’s stocks may not hold out. Humanitarian actors should therefore aim to pre-position supplies of non-perishable food items to enhance Kyiv’s resilience. Aid providers may also seek, through community networks, to identify those elderly and/or disabled people who still wish to leave, and arrange modes of evacuation that accommodate people with limited mobility given these residents are amongst the least likely to survive a blockade. Finally, aid actors should consider providing cash transfers to people who have lost their income sources due to the conflict.

UTILITIES AND INFRASTRUCTURE

Emergency heating plans are crucial.

There is running water in most districts, although some damage to the central network has been reported. Even in peacetime, Kyiv’s tap water is not considered safe to drink by residents; however, bottled water is still generally available. In addition to water, most households still have heat and electricity. While attacks have occured, Russian forces have not yet begun targeting Kyiv’s utilities and civilian infrastructure in earnest. Yet conditions in places such as Mariupol, where hits to electricity lines have caused outages at power plants and left residents freezing in their homes, underline the need to prepare emergency heating solutions like generators. Plans for emergency heating measures should prioritize households with children and the elderly.

PUBLIC ORDER

Repercussions of weapons proliferation for public safety are unclear; territorial defense forces may serve as primary partners in the humanitarian response.

Despite rumors of increased criminality and looting, especially attempts to rob abandoned apartments, there is no reliable information on the dynamics of local crime. Heightened public vigilance may deter criminal threats while also raising the risk of unnecessary violence. Authorities have issued small arms and light weapons to any resident eligible for the civilian territorial defense forces but it is unclear whether this has led to a significant increase in violence. So far, complaints about territorial defense troops generally concern checkpoints and restrictions on civilian freedom of movement rather than mistreatment of civilians or disorderly conduct. Yet there are scattered reports, which are uncorroborated, of residents calling on territorial defense personnel to punish neighbors who appear insufficiently patriotic (see section on “Attitudes to War”).

In the event of a humanitarian crisis, territorial defense forces may be required to assume greater responsibility for the distribution and coordination of humanitarian aid and civilian protection. Police, fire and rescue, and other first responders of the State Emergency Service appear to be functioning relatively efficiently.

SHELTER AND PROTECTION

The city’s bomb shelters are not all fit for purpose.

As Russian bombardment increases, there is an insufficient supply of protective shelters to meet the needs of the entire population. While many are sheltering in metro stations, there are not enough sufficiently protective shelters for the entire population. Many Cold War-era shelters have been demolished or repurposed and are no longer serviceable for their intended use. Generally, designated bomb shelters are not suitable for long-term habitation, with overcrowding, environmental contamination, and sanitation a challenge. These conditions could have negative public health consequences as the conflict wears on, particularly given the lingering COVID epidemic, and Ukraine’s high rates of tuberculosis, including drug-resistant varieties.

Some civilians are using the basements of their homes for shelter; however, these are often not deep, insufficiently reinforced with soil floors, subject to flooding, and in general unsuitable for long-term sheltering. Many people are reportedly staying in bus stops and public bathrooms, which may afford better structural protection but could also pose the risk of injuries from burst hot water lines and shattered tiles. While some are trying to stay in shelters, especially at night, many are simply sleeping at home. Risk awareness information has reportedly circulated advising people to stay in their apartment buildings, sleeping in corridors on the floor (taking advantage of structurally robust corridor walls) rather than in their rooms, and/or to remove/avoid/tape mirrors and glass that may shatter and create projectile threats in case of explosions.

INFORMATION AND COMMUNICATIONS

Social media is a powerful vector for life-saving information, as well as misinformation and disinformation.

Phone services are working normally. Information on civilian preparedness, protection, and risk awareness is circulating on a variety of media, including national TV channels and social media (e.g., Telegram channels, Facebook). Official Ukrainian social media channels are a powerful vector for protection information, as are speeches by President Volodymyr Zelensky and Kyiv mayor Vitaly Klichko. Misinformation is a concern, however. The Viber app, in wide use among the elderly, has been a conduit for dubious protection information. Russian disinformation remains ubiquitous, spread through anonymous Telegram channels, Instagram accounts, and sometimes hacked commercial media.

ATTITUDES TO THE WAR

Residents are set on a Ukrainian victory over Russia, but may also be open to certain compromises that do not entail giving up territory.

Anecdotally, morale among Kyiv residents seems to be relatively high. Public mood is characterized by increasing hostility to Russia, a belief that Ukraine is winning, support for armed resistance, and an unwillingness to contemplate ceding territory. This staunch patriotism coincides with a striking range of worldviews, illustrating the unifying power of Moscow’s aggression. Many young people view the war as a continuation of Ukraine’s efforts to overcome the legacy of Soviet rule. Yet one middle aged resident, who had previously told researchers that he dreamed of “USSR Part Two” and Ukraine’s unification with Russia and Belarus, now referred to Ukraine’s armed resistance as “our Great Patriotic War,” a reference to Soviet terminology for World War II. Another, who had previously said the Russians would never invade Kyiv, because “what the f- would they want us for?” now vowed, “we will be victorious, and we’ve already won.” He and others expressed confidence that Russia would capitulate by mid-April.

However, residents are not necessarily opposed to adjusting the country’s political course for the sake of peace. One interlocutor, for example, said no one around her would support Ukraine relinquishing territory, but that there was growing public acceptance of possible compromises on other Russian demands regarding matters of genuine controversy within Ukrainian society. One was “our membership in NATO, which does not want us anyway.” The other potential point of compromise, she said, concerned walking back state-level efforts to reduce the role of the Russian language in public life: referring to the ferocity with which Russian-speaking east Ukrainian cities were resisting invasion, she proclaimed, “Ukrainian Russian [language] exists, and is right now proving its right to exist.” Another Kyiv source, who concurred that the public mood favored “the liberation of all territories,” hypothesized that “even if someone were secretly ready to settle for less, they wouldn’t say a word, since the neighbors would immediately hand them over to the territorial defenses or the SBU [security service].”

AID RESPONSE

Local and ad-hoc initiatives are leading aid distribution efforts, making for a nimble but sometimes chaotic frontline response. The imposition of martial law has removed some bureaucratic hurdles to their work, but also reduced accountability for possible abuse or theft of aid.

Currently, the aid response in Kyiv (and Ukraine more broadly) appears to be dominated by local CSOs and informal, ad-hoc networks. This is a function of the country’s robust civil society, and the fact that public trust is chiefly vested in formal and informal local authorities. All this has made for a relatively flexible, adaptive and quick-acting response system. Yet it can lead to coordination problems, and access to essential goods is heavily dependent on personal connections.

At the same time, the imposition of martial law throughout the country has made the process of importing goods for humanitarian distribution more centralized, streamlined, and at times less transparent. On the one hand, martial law has meant simplified customs clearance and import procedures for aid deliveries. On the other hand, it has made it difficult, if not impossible for organizations shipping aid from abroad to monitor its distribution once it arrives in country: most humanitarian shipments crossing the state border are given over to the humanitarian headquarters of the relevant oblast, all of which are overseen by the State Coordination Center on food, water, medicine and fuel provision. (The only exceptions are for shipments requested by the Armed Forces of Ukraine, territorial defense forces or local authorities). Local administrations, emergency workers, and the civil society activists mentioned then distribute goods. Standard monitoring procedures are not currently required. This reduces the paperwork burden on volunteers and local organizations, but poses risks of corruption and ineffective goods distribution. It should be noted, however, that much of the work of Ukrainian civil society and ad-hoc aid groups still entails purchasing supplies within the country; these include food, water, medicine, toiletries, and fuel for private evacuation efforts.

Another key aspect of aid distribution in Ukraine that must inform the approaches of outside actors is the need to recognize that few domestic aid actors draw a firm distinction between civilians and Ukrainian combatants: both are seen as vulnerable groups in need of aid and moral support. A significant number of international actors are operating on similar principles. Among them are small, independent civil society organizations and volunteer groups, such as Polish charities and civil society organizations as well as local businesses and sports clubs that assist civilians and those on the frontlines. They are joined by networks of Western combat veterans providing evacuation assistance, aid supply distribution, and training and supplies for Ukrainian territorial defense and army units. Smaller Western faith-based organizations and networks have also had a notable presence in the informal system that is emerging. International aid organizations may be understandably leery of the appearance that humanitarian aid and military support are commingled or directed to the same target populations, practices which raise thorny questions concerning principles of neutrality. Some red lines should remain inviolable, namely the imperative to avoid direct support to armed groups. However, rather than demanding that partners observe strict neutrality, they should emphasize the need to fill gaps in and strengthen existing aid structures and modalities — not try to alter or compete with them. Aid actors should, however, seek to mitigate risks inherent to engagement in this aid ecosystem by establishing and communicating clear redlines with partners early, and consider safeguards including third-party monitoring.