Since mid-2020, the illicit drug industry has emerged as a touchstone aspect of the protracted crisis in Syria (see: The Syrian Economy at War: Captagon, Hashish, and the Syrian Narco-State). Once little known outside the Middle East, traffic in captagon pills is now widely regarded as a key funding mechanism of the regime of Bashar al-Assad. In large part, analysis concerning the Syrian narcotics trade has focused on the specific dimensions of regime involvement, often with an explicit emphasis on the mass-scale containerised drug shipments leaving Lattakia, where Assad regime control is uncontested.[1]Jorg Diehl, Mohannad al-Najjar, and Cristoph Reuter, “Syrian Drug Smuggling: ‘The Assad Regime Would Not Survive Loss of Captagon Revenues,’” Der Spiegel, 21 June 2022, available at: … Continue reading

Comparatively little attention has been paid to the dynamics of the narcotics industry in other parts of Syria. This is a consequential oversight. In crucial respects, the main dynamics of drug trafficking in southern Syria, the region most clearly shaped by narco-trafficking, differ from the conditions seen on the coast. Across southern Syria, the evidence of regime influence is muddied by factors that include competition and collusion among various intelligence agencies and militia groups and the narcotics entrepreneurs and smugglers who support them. In this context, trafficking requires touch points throughout local power structures, demonstrating the extent to which the Syrian captagon industry has become a bedrock feature of the broader war economy.

The following report analyses the drug trade in two governorates in southern Syria: Dar’a and As-Sweida. With a brief assessment of emerging trends in regional captagon trafficking, this report focuses on the local actors and networks that drive the trade in southern Syria, including narco-entrepreneurs, cross-border tribal and family networks, and military and security actors of varied backgrounds. The picture that emerges is highly localised, diverse, and seemingly decentralised. While the Assad regime’s role in the drug industry should not be downplayed, the evidence drawn from southern Syria suggests that a bottom-up analysis is needed to understand — and ultimately counter and interdict — Syrian narcotics networks.

Key Findings

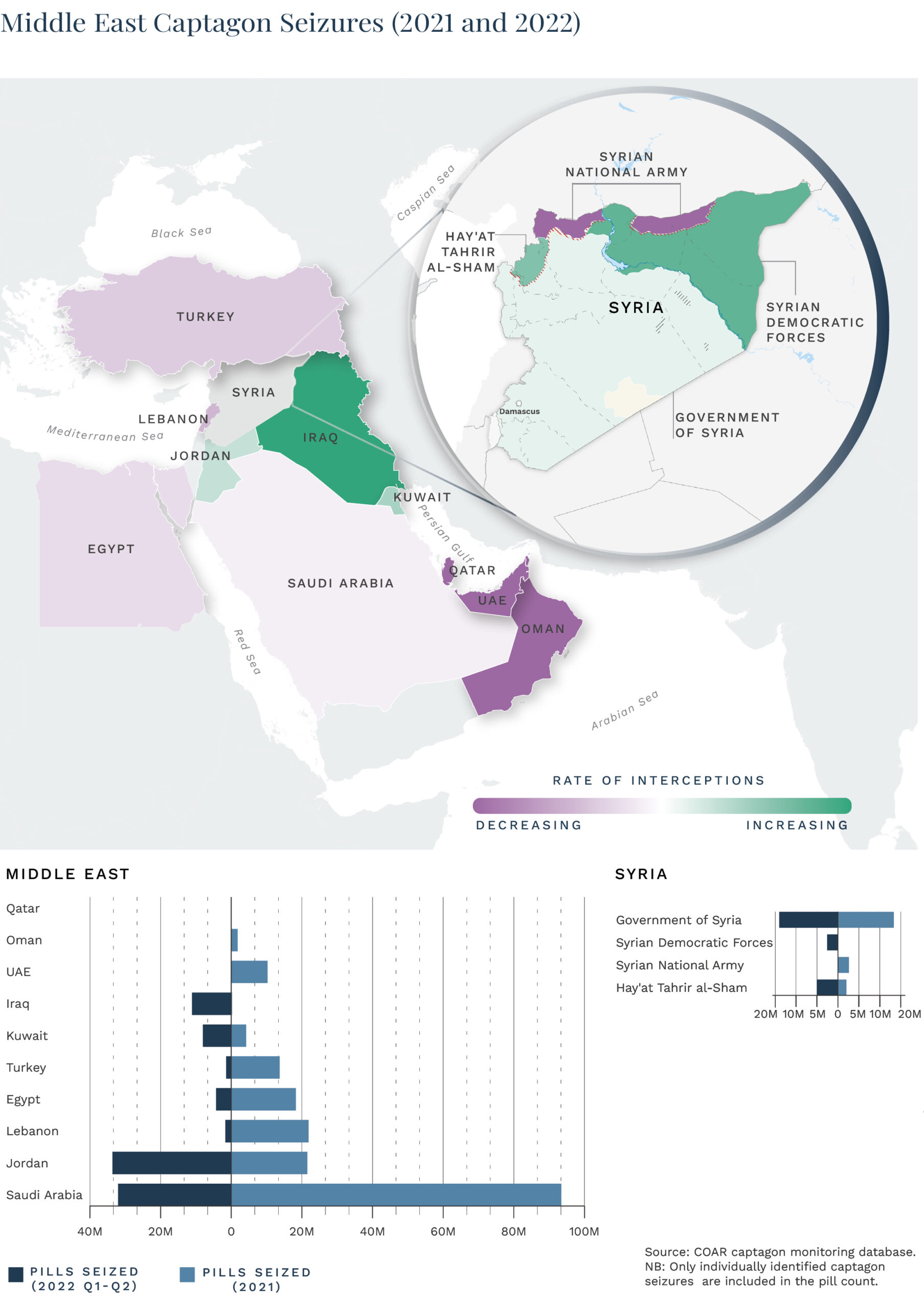

- Regional states have intercepted more than 100 million captagon pills in the first half of 2022, setting the year on track for a nominal decline compared with 2021.

- Captagon seizures in Gulf states, including the UAE and Saudi Arabia, are on pace to decline for 2022, likely reflecting a combination of upstream interdiction in transit countries and changes to Gulf states’ public communications strategies regarding Syria and/or narcotics.

- Significantly declining captagon seizures in Lebanon and Turkey in 2022 have been offset by a surge in interdiction in Jordan and Iraq, the latter of which has emerged as a key transit route to the Gulf, thus implicating adjoining areas of Syria that are administered by the Syrian Democratic Forces as an under-recognised narcotics thoroughfare.

- Although there is no single, fixed modus operandi for narcotics trafficking in Dar’a and As-Sweida, the fluid networks involved in the trade share one defining characteristic: They link local stakeholders and key intermediaries with powerful military or security services, most commonly Military Intelligence. In many cases, reconciled opposition leaders now operate as focal points for Syrian security services.

- The diversity observed within local narcotics networks is likely a systemic adaptation allowing the drug trade’s most pivotal actors — the Assad regime and Hezbollah — to convert a disadvantage (e.g., limited direct control in southern Syria, a region beset by factionalism) into influence and profit.

Recommendations

- Donor agencies should be wary of theories of change that propose to use targeted aid initiatives to deter Syrians from participating in local narcotics trafficking activities. The militia and smuggling groups that dominate the trade will likely be resistant to change, while successful smuggling, though perilous, can pay thousands of dollars — offering incentives which donors are unlikely to match through aid activities.

- Instead, humanitarian and developmental assistance can and should seek to alleviate the conditions that drive Syrians to consume captagon, including by exploring the provision of drug treatment options. There are preliminary indications that such programming may be possible — with requisite do no harm safeguards — in northern Syria in particular.

- Aid activities can be made resilient to potential crossover with narcotics networks by applying a localised conflict-sensitivity lens, particularly in due diligence and compliance practices.

- Legislative and law enforcement efforts to undermine captagon’s value as an Assad regime financing mechanism are at risk of misfiring if they fail to account for the networks of ancillary actors that have become entrenched within the Syrian narco-economy.

- The international community should continue to monitor for adaptations to Syrian narco-trafficking. If current captagon revenues are threatened, new transit routes, narcotic types, and methods of drug delivery are likely to emerge.

An Evolving Understanding of a Changing Industry

In April 2021, COAR published a detailed report that was among the first assessments to document Syria’s emergence as a narco-state, based on an analysis of “industrial-scale drug profiteering, which has been largely captured and controlled by narco-entrepreneurs linked to the regime of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad and the regime’s foreign allies.” (see: The Syrian Economy at War: Captagon, Hashish, and the Syrian Narco-State). Since then, captagon trafficking has continued to expand and evolve inside Syria and abroad.

Size: The Industry Has Widened

Global captagon seizure data compiled by COAR indicate that foreign states intercepted more than 170 million captagon tablets explicitly linked to Syria in 2020.[2]Figures compiled by COAR exclusively represent individual interceptions for which Syria is identified as the source country. For this reason, composite figures or cumulative totals are excluded. In 2021, the figure jumped to 280 million, and far larger by some estimates.[3]Caroline Rose and Alexander Söderholm, “The Captagon Threat: A Profile of Illicit Trade, Consumption, and Regional Realities,” New Lines Institute, 5 April 2022, available at: … Continue reading Yet interception data are not necessarily an accurate reflection of the underlying dynamics. The uptick in seizures coincides with a growing regional awareness of captagon trafficking, which has translated into tightened inspection protocols, particularly for shipments linked to Syria.

While it is unclear whether Syria’s actual captagon output has grown proportionally with interceptions, the figures are sufficient to indicate that the narcotics industry remains a sizable regional issue, now and for the foreseeable future. New Lines Institute has estimated that the total value of captagon interceptions in 2021 reached 5.7 billion USD.[4]Ibid. Based on narrow selection criteria and a conservative evaluation of market prices, COAR’s assessment (Figure 1) indicates a comparatively lower value range.[5]Based on information from regional local media and narcotics industry insiders, COAR estimates that captagon has a likely street value ranging between 5 USD and 15 USD per pill outside Syria, and … Continue reading By this measure, foreign authorities intercepted suspected Syrian captagon tablets with a probable street value of between 2.8 billion USD and 4.2 billion USD in 2021. In the first half of 2022, interceptions worth an estimated 1 billion USD and 1.5 billion USD have occurred.

Figure 1

| Market Value Estimate of Syrian Captagon Interceptions* | ||

| Low | High | |

| 2022 (Q1-Q2) | $1 billion | $1.5 billion |

| 2021 | $2.8 billion | $4.2 billion |

*Based on monitoring data compiled by COAR.

Scope: Emerging Routes

Transit dynamics have also evolved. Ports in Africa (e.g. Sudan and Nigeria) and Asia (e.g. Malaysia[6]The seizure of 94.8 million captagon pills at Klang Port by Malaysian authorities, acting on a Saudi tipoff, is the largest-ever intercepted captagon shipment. Mariam Nihal, “Saudi tip-off leads to … Continue reading) emerged in 2021 as new waypoints used to evade the detection of narcotics concealed in mass-scale containerised shipments. The most noted and persistent regional change, however, concerns trafficking patterns with Syria’s southern neighbours, Iraq and Jordan. Since 2020, Iraq has emerged as a major captagon transit country and a market in its own right, implicating adjacent areas of Syria that are controlled by Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), the territorial entity that has practised the least robust counter-narcotics efforts in recent years (Map 1, inset). In the first half of 2022, Iraq has intercepted more than 11 million captagon tablets from Syria, a staggering increase compared with a mere 200,000 in 2021. Jordan has seized 33 million pills through June 2022, roughly double the number intercepted in 2021. Lebanon, meanwhile, has seen a substantial dropoff in interceptions, declining from 21.9 million in 2021 to 1.6 million in the first half of 2022.

Gulf states are observing divergent trends. Captagon seizures in Saudi Arabia are falling compared with 2021. Despite major seizures in the first half of 2022, Saudi Arabia is on pace for a 31% reduction in captagon seizures linked to Syria. Oman, Qatar, and the UAE have reported no captagon interceptions in 2022, despite notable hauls in 2021. It is not clear if the declines in those states reflect changes to underlying trafficking dynamics or other factors, such as changing communications strategies regarding interceptions, although it is unlikely that interceptions have halted altogether. Upstream interceptions in key intermediary states, particularly Iraq and Jordan, have likely reduced captagon flows to the Gulf.

Inside Syria

Data concerning captagon seizures inside Syria have been comparatively limited. Although northwest Syria remains a particular blind spot in captagon research, local sources report an anecdotal increase in drug use and signs of smuggling since 2020. Cross-border smuggling of captagon into Turkey remains curtailed, to a large extent, by interdiction efforts on the part of Turkish proxy forces. In Idleb, Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) intercepted approximately 5 million captagon pills in the first half of 2022.[7]Over 2021 and 2022, HTS reported that major shipments it seized were bound for Turkey and Saudi Arabia. In northern Aleppo, various Syrian National Army (SNA) factions have launched well-publicised crackdowns on traffickers, but have seized smaller quantities of the drug: 2.6 million pills in 2021, and a mere 2,00 pills so far in 2022. SNA groups have publicly immolated large quantities of seized narcotics to demonstrate that the pills will not be recirculated — a rarity among intercepting parties in Syria or elsewhere. So far in 2022, Turkey has seized 1.4 million captagon tablets of Syrian origin, putting it on pace for a substantial decrease in volume compared with 2021 (13.8 million).

In eastern Syria, the Asayish security forces intercepted 2.5 million pills in a Quamishli warehouse in March, the only seizure reported in SDF-controlled areas in the first half of 2022.[8]Abdul Halim Suleiman, “The Self-Administration in Syria Seizes more than 2.5 Million Captagon Pills,” Independent Arabia, 23 March 2022, available at: . The pills were reportedly destined for the Kurdistan Region of Iraq, drawing attention to the use of northeast Syria as a thoroughfare to reach Iraq, which shares an extensive border with areas of Syria administered by the SDF as well as the Government of Syria. Meanwhile, Syrian government authorities have seized more captagon in 2022 than any other territorial actor in the country, although the vast majority of the 14 million pills seized came from a single bust in Hama.[9]Akhbar Al-Youm, “The Interior Ministry in Syria Seizes More Than 2.3 Million Captagon Pills,” 29 June 2022, available at: .

How Does the Drug Economy Work in Southern Syria?

The limited scope of captagon seizures across Syria indicates that authorities in all regions of the country are, to some extent, willing to turn a blind eye to the drugs trade, or are complicit outright. Yet the degree to which local stakeholders facilitate narco-trafficking is highly variable, as are the identities of the actors involved. Nowhere is the complexity of this dynamic more evident than in southern Syria, as illustrated by case studies drawn from two governorates, Dar’a and As-Sweida.

Dar’a

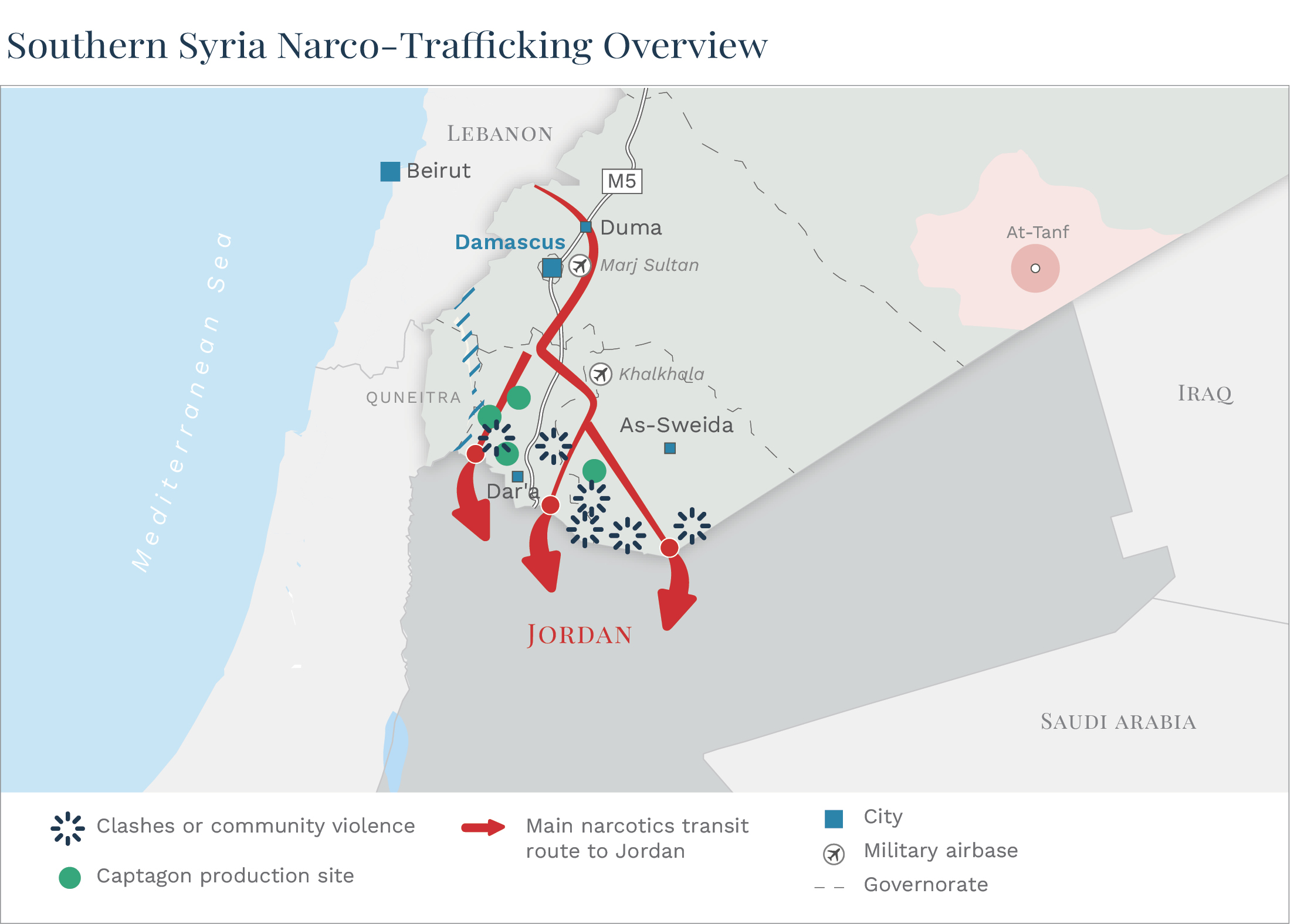

In broad terms, Dar’a Governorate can be understood both as a key drug production region and as the main thoroughfare for the transit of Syrian (or imported Lebanese) narcotics into Jordan, and from there, towards the Gulf. Presently, drugs cross into Jordan primarily along Dar’a’s western border with Quneitra Governorate and its eastern rural expanses, through villages such as Tisiya and Smaqiyat, near As-Sweida Governorate. The official Nassib-Jaber border crossing is used as a drugs shipment route into Jordan,[10]Joseph Daher, NIzar Ahmad, and Salwan Taha, “Smuggling between Syria and Lebanon, and from Syria to Jordan: the evolution and delegation of a practice,” European University Institute Middle, … Continue reading albeit infrequently, owing in part to its intermittent closures and reduced overall volume of traffic. In such instances, drugs are concealed among licit items such foodstuffs and industrial products.

At the centre of the drugs trade in Dar’a are local narco-entrepreneurs, often reconciled former opposition commanders backed by local militia groups. Crucially, these local actors operate as proxy forces of various security services, a relationship that provides the latter with both a buffer from the local community. While Western analysts and Jordanian officials[11]Ben Hubbard and Hwaida Saad, “On Syria’s Ruins, a Drug Empire Flourishes,” The New York Times, 5 December 2021, available at: … Continue reading alike have largely attributed drug trafficking in southern Syria to Hezbollah and the Fourth Division — commanded by Maher al-Assad — the reality is far more ambiguous, and local sources identify identify Military Intelligence as the security service that is most actively involved in captagon logistics, production, and transportation across southern Syria.

Nonetheless, numerous captagon laboratories have been identified across Dar’a,[12]Aasim al-Zouabi, “Increased Iranian presence in the smuggling of drugs in South Syria,” al-7al.net, 20 May 2022, available at: . reflecting the atomisation of power and influence in the region. Affiliates of the Military Intelligence branch operate mills in Nawa and Kharab Shahem in the southwestern Dar’a countryside and Ghasm in eastern Dara, while Syrian members of Hezbollah maintain captagon facilities across the Lajat region.[13]Ibid., and local sources. Although smuggling and transport routes adapt according to prevailing conditions, supplying these facilities with chemical inputs sourced from Lebanon requires the assent of a range of military and security actors positioned throughout western and central Syria, among which are Military Intelligence, the Fourth Division, the Republican Guard, and Hezbollah. Nonetheless, within southern Syria itself, local affiliates of the security branches can be considered the dynamo of the narcotics trade. The brief case studies that follow demonstrate the range and diversity of local intermediaries and narco-entrepreneurs involved in the trade. (NB: In order to retain a focus on the structure of the trade, stakeholders are referred to by initials. Sources that may reference individuals by name have been withheld.)

Case Study No. 1 – AK: Opportunistic Smuggler and Narco-Pioneer

The trajectory of AK is indicative of the way in which narcotics trafficking has spilled over into — and in some ways now dominates — the broader illicit economy in Syria. AK was prominently involved in smuggling arms and cigarettes prior to the conflict and, after southern Syria came under the control of the Free Syrian Army (FSA), joined an opposition faction headed by members of his extended family in order to ease his illicit activities. When the southern opposition collapsed, AK reconciled with Damascus and recruited numerous relatives to the Fourth Division. AK is understood by local sources to be the first actor to build significant captagon production capacity in southern Syria, in Kharab Shahem. Precursor chemicals reach these facilities from Lebanon, securing passage via the Fourth Division. Captagon trafficked by AK is often consigned for domestic consumption. Members of AK’s militia — 150 strong and mostly members of his clan — have been attacked in recent years due to their association with drug trafficking.

Case study No. 2 – AH: Hezbollah Antagonist and Western Dar’a Narcotics Logistician

AH is a leading actor securing transportation routes for narcotics smuggling in the Yarmouk Basin, including near the remote border town of Koya, in southwestern Dar’a, and his activities exemplify the degree to which competition bordering on violence exists among narcotics networks. A former military commander in the Southern Front’s Yarmouk Army, AH reconciled with the Government of Syria and remains influential as a smuggler. Notably, AH has clashed with Hezbollah cells, whom he has accused of attempting to assassinate him and other former opposition commanders from the Yarmouk basin. AH is not the only case of a prominent drug trafficker who has had historically hostile relations with Hezbollah. One such actor, a former member of the National Defence Forces (NDF), has since become a key Hezbollah ally, suggesting that these ties are fluid and form on the basis of pragmatic considerations.

Case Study No. 3 – AZ: Opposition Commander Turned Military Intelligence Kingpin

AZ is considered by local sources as a leading figure in the narcotics networks of eastern Dar’a Governorate, including local production and smuggling. After his release from a Syrian government prison in 2012, AZ became a rebel commander and participated in the Jordan-based Military Operations Centre (MOC)[14]The MOC was a structure devised to channel Western and Arab support to the Syrian opposition and coordinate their activities. but reconciled with the Government of Syria when the southern opposition collapsed. He has since mobilised a militia group affiliated with Syrian Military Intelligence, ostensibly as a counterbalance against the Fifth Corps, also composed of reconciled opposition fighters. AZ has drawn between 60 and 150 recruits to the group, and they are deployed mostly at the Nassib border crossing, where close family members of AZ operate a resthouse and enjoy exemptions from customs inspections. AZ’s group has carried out an attack on the Nassib customs house and multiple attacks against opponents and insurgent groups, often targeting former opposition commanders and fighters who have refused to reconcile, as well as bedouin collectives and farmers — frequently charging them with being ISIS affiliates or standing behind assassination attempts.

As-Sweida

Although As-Sweida Governorate is often interpreted through the inward-looking tendencies of the Druze political leadership, local patterns of drug trafficking show the limited extent to which the region has been able to isolate itself from the trends shaping Syria. The Druze militia Rijal al-Karameh, the region’s socio-religious power brokers, have resisted (and publicly condemned) embroilment in the narcotics industry. Nonetheless, the drug trade has proliferated via complex networks linking bedouin smuggling cells centred on the fringes of the governorate with military and security actors in the Syrian interior. Although smuggling (e.g. in livestock, food products, cigarettes, and to a lesser extent, arms and narcotics) has been a pronounced feature of the region throughout Syria’s modern history, captagon smuggling has blossomed since 2015 and accelerated further since the Syrian government’s capture of the south in 2018. As in Dar’a, Military Intelligence is the local security actor with the greatest involvement in narcotics trafficking networks, supported by key local stakeholders.

Case Study No. 1 – RF: Flashpoint of Druze Resistance

A key narcotics facilitator in As-Sweida, RF has clashed frequently with the region’s Druze leadership. By way of its affiliation with Syrian Military Intelligence, RF’s 50-strong armed group plays a prominent role in transport and shipment of narcotics from Damascus to as-Sweida, adding to myriad local grievances that have led local Druze leaders to repeatedly call for the Syrian government’s security apparatuses to disassociate themselves from RF. In 2021, RF’s armed group launched an attack on the State Security branch, reportedly culminating from a dispute over the division of drug proceeds between the State Security and Military Intelligence branches. In late July 2022, Rijal al-Karameh launched a series of coordinated attacks on RF’s armed group in the towns of Atil, Shahba, and Salim, in central As-Sweida. Though triggered by events not directly related to narcotics, the clashes resulted in the takeover of the group’s headquarters near Atil, where pill presses used for manufacturing captagon were reported.

Case Study No. 2 – MR: Tribal Ties and Cross-Border Smuggling

Among the most noted actors involved in narcotics smuggling at the border of As-Sweida and Jordan is MR, a notable of the al-Ramthan tribe, which wields influence across the al-Hammad desert plain, an expanse that stretches across southeastern Syria, Jordan, western Iraq, and northern Saudi Arabia. MR reportedly enjoys close and extensive relations with Syrian political circles and the security apparatus, in addition to Hezbollah, which serves as a connection to narcotics sourced via the border community of Qusayr. Shipments arriving from Lebanon via Damascus must pass through various key points in As-Sweida Governorate, where they are warehoused in facilities affiliated with Military Intelligence, before being divided and prepared for cross-border transport.

Conclusion

As the foregoing case studies illustrate, drug networks in southern Syria integrate an array of actors, including security agencies, Hezbollah and its local affiliates, reconciled former opposition leaders, purpose-formed militia groups, and bedouin facilitators. In contrast with the widely held understanding of narcotics networks on the Syrian coast, in southern Syria, narcotics trafficking is highly fragmented. Several plausible explanations for this ‘decentralisation’ of the drug trade exist.

- Power in southern Syria is atomised, reflecting the piecemeal fashion in which the region has been divided, pacified, and governed. In many areas, central authorities have ceded genuine power to local actors, including many formerly affiliated with opposition groups.

- In many cases, key narcotics stakeholders represent powerful community structures, such as tribes or militia groups. By tapping these networks, security services are able to co-opt existing technical capacity and manpower.

- Coordinating the narcotics trade through locally rooted narco-entrepreneurs grants regime-linked security services plausible deniability in the face of international pressure over regional narcotics spillover.[15]Ben Hubbard and Hwaida Saad, “On Syria’s Ruins, a Drug Empire Flourishes,” The New York Times, 5 December 2021, available at: … Continue reading

- Cross-border smuggling networks, particularly those rooted in Arab tribes, often have extensive transnational reach, including to lucrative markets in the Arabian Peninsula.

References[+]

| ↑1 | Jorg Diehl, Mohannad al-Najjar, and Cristoph Reuter, “Syrian Drug Smuggling: ‘The Assad Regime Would Not Survive Loss of Captagon Revenues,’” Der Spiegel, 21 June 2022, available at: https://www.spiegel.de/international/world/syrian-drug-smuggling-the-assad-regime-would-not-survive-loss-of-captagon-revenues-a-b4302356-e562-4088-95a1-45d557a3952a. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Figures compiled by COAR exclusively represent individual interceptions for which Syria is identified as the source country. For this reason, composite figures or cumulative totals are excluded. |

| ↑3 | Caroline Rose and Alexander Söderholm, “The Captagon Threat: A Profile of Illicit Trade, Consumption, and Regional Realities,” New Lines Institute, 5 April 2022, available at: https://newlinesinstitute.org/terrorism/the-captagon-threat-a-profile-of-illicit-trade-consumption-and-regional-realities/. |

| ↑4 | Ibid. |

| ↑5 | Based on information from regional local media and narcotics industry insiders, COAR estimates that captagon has a likely street value ranging between 5 USD and 15 USD per pill outside Syria, and roughly 1 USD inside the country. |

| ↑6 | The seizure of 94.8 million captagon pills at Klang Port by Malaysian authorities, acting on a Saudi tipoff, is the largest-ever intercepted captagon shipment. Mariam Nihal, “Saudi tip-off leads to $1.2bn Captagon drug bust in Malaysia,” The National, 25 March 2021, available at: https://www.thenationalnews.com/gulf/saudi-arabia/saudi-tip-off-leads-to-1-2bn-captagon-drug-bust-in-malaysia-1.1191083. |

| ↑7 | Over 2021 and 2022, HTS reported that major shipments it seized were bound for Turkey and Saudi Arabia. |

| ↑8 | Abdul Halim Suleiman, “The Self-Administration in Syria Seizes more than 2.5 Million Captagon Pills,” Independent Arabia, 23 March 2022, available at: . |

| ↑9 | Akhbar Al-Youm, “The Interior Ministry in Syria Seizes More Than 2.3 Million Captagon Pills,” 29 June 2022, available at: . |

| ↑10 | Joseph Daher, NIzar Ahmad, and Salwan Taha, “Smuggling between Syria and Lebanon, and from Syria to Jordan: the evolution and delegation of a practice,” European University Institute Middle, Wartime and Post-Conflict in Syria Project, 2022, available at: https://cadmus.eui.eu/handle/1814/74453. |

| ↑11, ↑15 | Ben Hubbard and Hwaida Saad, “On Syria’s Ruins, a Drug Empire Flourishes,” The New York Times, 5 December 2021, available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2021/12/05/world/middleeast/syria-drugs-captagon-assad.html. |

| ↑12 | Aasim al-Zouabi, “Increased Iranian presence in the smuggling of drugs in South Syria,” al-7al.net, 20 May 2022, available at: . |

| ↑13 | Ibid., and local sources. |

| ↑14 | The MOC was a structure devised to channel Western and Arab support to the Syrian opposition and coordinate their activities. |