Executive Summary

Resilience, social cohesion and wellbeing are interrelated indicators of a community’s overall ability to function and sustainably meet the needs of its members. A resilient community can withstand shocks; a socially cohesive community is inclusive and safeguards diversity; and a community that has attained a high level of wellbeing enjoys a multitude of conditions identified as crucial to individuals’ ability to reach their potential individually and as a community. In northern Syria, programmes to effectively strengthen community resilience, social cohesion and community wellbeing would enable communities to function more independently and reduce their dependence on aid. However, after more than a decade of conflict and ensuing crises, as well as the devastation of the February 2023 earthquakes in certain areas, an abrupt and complete shift away from emergency lifesaving support in favour of support for systemic resilience would be premature in northern Syria. A less disruptive and more durable approach to the support of resilience, social cohesion and wellbeing in northern Syria would seek to enhance the lifesaving dimensions of existing systemic resilience interventions, expand the delivery of such programmes across more target geographies, and improve the impact and sustainability of these initiatives through greater localisation and integration across the response.

Key Recommendations

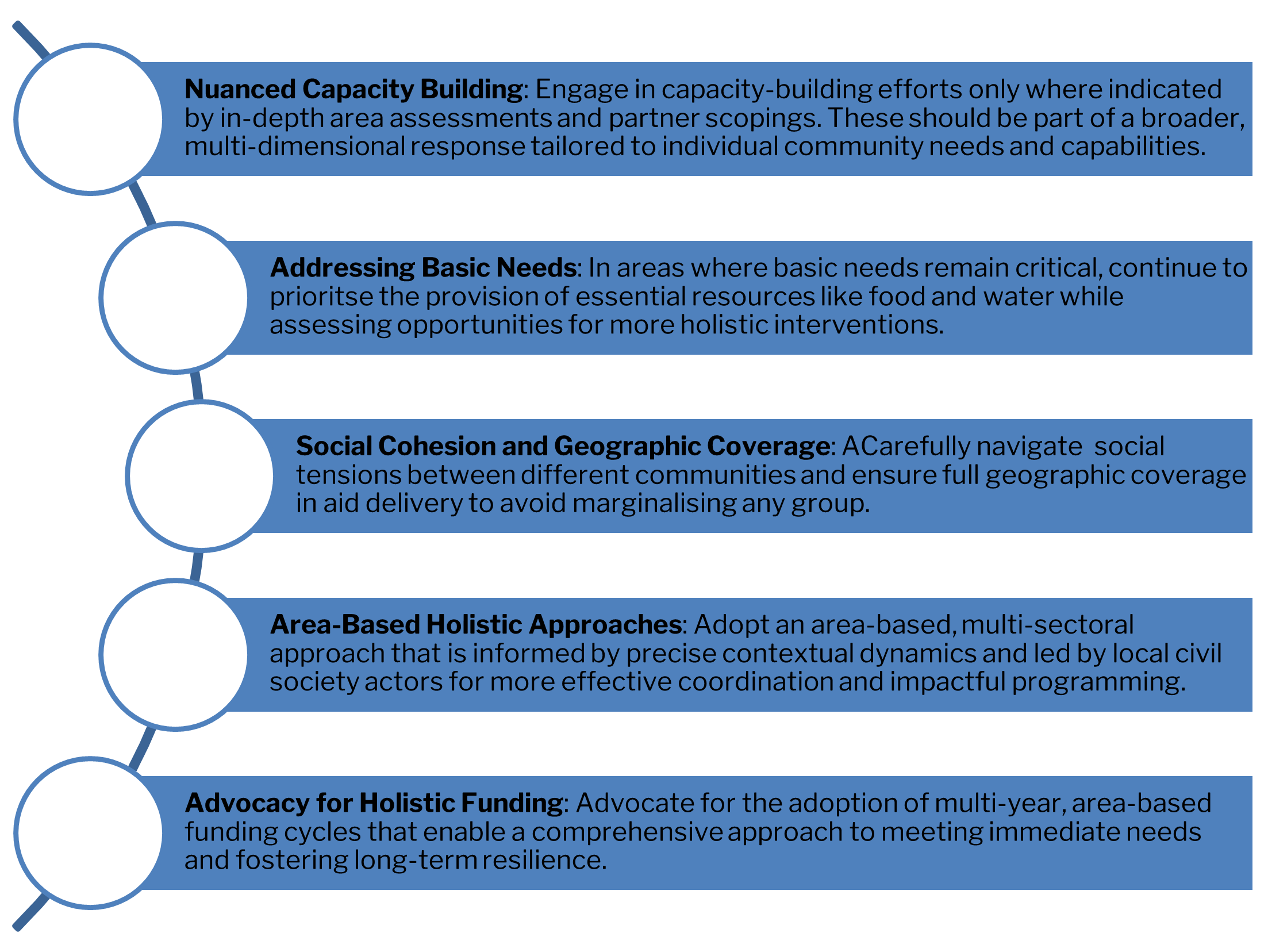

- The Aid Fund for Northern Syria (AFNS) should adopt a ‘nexus’-oriented approach, prioritising communication, coordination and collaboration: The adoption of a strategic, multi-sectoral, area-based approach to programming would allow AFNS and the response actors it supports to de-silo programming and ensure that resilience, social cohesion and wellbeing programming are mainstreamed across a comprehensive and sustainable response that addresses immediate needs while gradually strengthening systems and reducing aid dependence. To execute such a nexus approach, in-depth target area assessments and partner scopings should be carried out to inform the design and delivery of highly-localised interventions, led by civil society actors across northern Syria, that aim to address the full spectrum of present needs while investing resources and delivering assets that can bolster community resilience over time.

- Push the response towards multi-sectoral programming: Future AFNS allocations should encourage (or require) cross-sectoral collaboration, with resilience, social cohesion and wellbeing interventions mainstreamed across response programmes, and ensure tangible support, assets or investments are coupled with resilience, social cohesion and wellbeing projects.

- AFNS should adopt an area-based approach, and insist its partners carefully tailor interventions to the local context: Northern Syria comprises communities facing myriad different political, security, humanitarian and development realities. What is feasible in certain communities of northern Aleppo should not be assumed to be feasible in Idleb — or even in communities elsewhere in northern Aleppo. To be safe and effective, programmes must be carefully designed to navigate the particular challenges of each target area, including local authorities, security threats, and the situation of local communities.

- Enhance localisation to improve impact and sustainability: Localisation done well can help break down divisions among different groups while avoiding entrenching inequality and exclusion within and among communities. Political biases and particular agendas of local stakeholders and potential partners should be closely tracked and navigated to avoid unintended harms. Continuous consultation by AFNS, its partners, and appropriate intermediaries with a broad set of stakeholders can facilitate access, ensure community participation, maximise the range of needs met, and enable sufficient local ownership for positive interventions to outlive project cycles. Allowing for gradual change over time is essential for resilience, social cohesion and wellbeing programming, as none of these areas can be addressed in a single project period.

- Adopt a strategy to invest in the administrative and programming capacity of civil society: To address the challenge posed by a lack of highly professionalised civil society organisations across target areas, AFNS should develop a networking strategy or sub-granting mechanism to allow for consistent, long-term investment in the technical skills of civil society actors. This would allow smaller, emergent civil society actors to access resources and skills necessary to their growth and successful operations, and contribute to a larger set of potential implementing partners over time. The sub-granting mechanism should be flexible, and available for investment in local actors’ systems development where needed as well as for use in building civil society’s technical programme capacity where appropriate. Exact use of the mechanism should vary in line with the precise needs of local actors, which should be closely assessed prior to engagement and on a rolling basis throughout projects.

- Develop highly-localised risk mitigation strategies to enable safe operations: Northwest Syria, which AFNS understands to comprise the Idleb governorate as well as northern Aleppo and the Ras al-Ain-Tell Abiad area (RAATA), presents response actors with an uneven landscape of operational risks. Prominent among these are the challenges faced within Idleb governorate, where territory is under the control of Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), a designated terrorist entity that has been placed under sanctions by multiple states, including prominent international donors within the Syria response. In consequence, the findings of this research cannot be applied to the same extent or in the same fashion across all areas. In areas under HTS, and elsewhere where security or political risks are considered too high, direct engagement with many local stakeholders will be impossible. Due diligence for operations in these areas must be especially robust, and compliance risks should be carefully mapped and used to inform appropriate intervention strategies prior to programme delivery.

- Extend implementation timelines: To better serve communities, meet critical needs, and ensure sustainability over time, AFNS should extend funding cycles and response actors should stretch programme timelines beyond narrow ‘emergency’ windows and consider the long-term viability of interventions over at least eighteen months, and ideally over several years. One respondent indicated that twenty-four months is the minimum period their organisation will accept to attempt effective, holistic interventions, but that even two years is far less than ideal for real investment in communities’ early recovery.[1] While some donors have pivoted to longer project cycles, vast disparities across the response landscape hinder coordination among aid actors, impose undue burdens on local civil society, and constrain the life-saving impact of programmes delivered across northern Syria. Regardless of project timelines, all interventions should seek to invest crucial resources in target communities, so that stakeholders can continue implementation efforts and better meet community needs beyond the end date of any given programme. Finally, all project timelines should build in necessary windows to effectively evaluate impact, so that positive progress and lessons learned can be documented, as these can feed into the design of future programmes. Without the foundations of such an evidence and experience-based approach, harmful aspects of siloed programming are likely to impede response innovations and slow any reduction of communities’ aid dependency over time.

Methodology

This report was prepared by the Center for Operational Analysis and Research (COAR) in order to provide evidence-based analysis to help inform the decision making of the Aid Fund for Northern Syria (AFNS) with respect to programming priorities, funding allocations, and intervention strategies to improve the resilience, social cohesion and wellbeing of communities throughout northern Syria. The analysis and recommendations presented in this report are based upon research conducted by COAR in July and August 2023. Research methods included eight key informant interviews with a range of stakeholders, including local community members and response actors based throughout northern Syria. Four additional interviews were conducted with international experts and humanitarian responders working remotely to support interventions across target areas. In addition, this research draws upon examination of relevant public and confidential data and reports, and review of news media and other relevant publications. For their security, individual sources are not identified.

1. Community Resilience, Social Cohesion and Wellbeing in Practice

| 1) Existing resilience initiatives, including local unions organised around a range of stakeholder priorities, such as agricultural unions for farmers and women’s unions centred on feminist interests, have demonstrated a positive impact on enhancing lifesaving outcomes in northern Syria.

2) Despite challenges posed by instability, uncertainty and fluctuations in the political and security landscapes of northern Syria, concrete opportunities exist for AFNS to enhance area-based programming. Existing initiatives can be better integrated into current humanitarian and early recovery efforts through bolstered efforts to de-silo programming and ensure multidimensional, mutually reinforcing interventions are led by members of affected communities. |

Conceptual Application: Community Resilience, Social Cohesion, and Wellbeing

Community resilience, social cohesion, and wellbeing are interrelated but distinct concepts that refer to different aspects of communities’ abilities to meet the needs of their members in a sustainable manner. Scholarly and practitioner definitions of each term vary but general trends of understanding and operational use can be identified for each.

Of the three, community resilience tends to be the term most succinctly and consistently defined across written materials. While in-depth practitioner guides to community resilience can be more comprehensive and lengthy, numerous concise and abstract sources tend to simplify the term as “a measure of the sustained ability of a community to utilise available resources to respond to, withstand, and recover from adverse situations.”[2] The more detailed, technical sources do not contradict this basic definition, but rather layer a higher degree of nuance or contextualisation into their explanations of community resilience.[3] The general tide of shared understanding among written sources was mirrored throughout this research, as respondents described community resilience with apparent ease and a high degree of consistency. Most participants in this research quickly explained community resilience as “a community’s ability to withstand shocks.”

Social cohesion is defined by scholars and stakeholders with a slightly higher degree of variation than ‘community resilience.’ At a fundamental level, social scientists consider that ‘social cohesion’ “refers to the extent of connectedness and solidarity among groups in society. It identifies two main dimensions: the sense of belonging of a community and the relationships among members within the community itself.”[4] Practitioners engaged in humanitarian interventions in northern Syria tend to define social cohesion in more plain and pragmatic language, with most considering “coordination”[5] an integral element of a socially cohesive community. Respondents flagged a number of other concrete indicators of social cohesion, including “unity”, “harmony”, “inclusivity”, “non-discrimination”, “peace” and the capacity to work collectively towards lasting peace.

Definitions of ‘wellbeing’ generally appeared most varied across the literature review, likely because the notion of community health or wellness is so broad as to comprise almost all aspects of community life. As a result, perceptions of ‘wellbeing’ can fluctuate considerably depending on how it is measured. Leading research identifies wellbeing as “the combination of social, economic, environmental, cultural, and political conditions identified by individuals and their communities as essential for them to flourish and fulfil their potential”.[6] With this definition, social scientists embrace a flexible technical definition of community wellbeing that broadly identifies a range of conditions necessary for communities and their individual members to thrive, but defers to particular communities and their individual members to select the aspects of these that are critical to them. This approach allows for the creation of localised, operational definitions of ‘community wellbeing’ that are highly adaptable. Ultimately, the broad definition allows social scientists to defer to people within communities to identify individually and collectively the conditions most important to them with respect to facilitating, building and maintaining ‘community wellbeing.’ Respondents to this research provided a range of explanations for the concept of community wellbeing, including: “stability”, “political stability”, “economic sufficiency”, “comfort”, “a stable, happy life for all segments of society”, “high quality of life”, and the “sustainability or permanence” of these conditions.

With respect to the above definitions, the most problematic assumptions identified by both social scientists and respondents to this research centre around timing, flexibility, and localisation. Generally speaking, improvements in community resilience, social cohesion and wellbeing can only be achieved slowly, over time. To be sustainable, any intervention must thus be designed to survive and thrive on a longer timeline than those of narrow project cycles and donor funding windows. Additionally, definitions of these concepts must be flexible, to enable them to be tailored to the specific situation of target communities so that baselines, interventions and outcomes can align with communities’ individual needs. Social scientists and respondents to this research identify localisation as the means to facilitate gradual change over time and ensure programming is rooted in each community’s reality, is designed to address its needs, and is carried out sustainably over multi-year periods. As respondents highlighted throughout this research, such a locally-driven approach is particularly needed across the diverse landscape of northern Syria, where ethnic, religious, linguistic and tribal identities vary as widely as political ideologies, humanitarian needs, and opportunities for development and economic growth.

The main dissonance between assumed best practice — wherein communities would design, lead and implement over time efforts to enable their own resilience, social cohesion and wellbeing — and the reality of the response in northern Syria, hinges on donor rigidity. Respondents highlight that most donors operate one-year funding cycles, which allow for eight or nine months of project implementation — at most — and impose a heavy, time-consuming administrative burden on local actors in terms of securing funding, reporting on activities, and auditing projects. Energy devoted to applying and re-applying for financial support and demonstrating delivery, impact and compliance would be better spent addressing community needs, according to community members and responders. Compliance, monitoring and evaluation could be better integrated and carried out over time, while the extensive demands of proposal writing, selection processes and audits could be greatly eased with a switch to multi-year intervention strategies. Respondents engaged in the Syria response for over a decade shared that they continue to provide emergency relief to individual beneficiaries, as well as respond to community needs, and invest in the capacity development of local actors and entities to provide for their own requirements in future. They contend that this three-tier strategy is difficult to implement while navigating short funding cycles and projects delivered in relative isolation from other response activities.[7]

This becomes a challenge because few donors — or response actors — are comfortable committing to long-term funding strategies in a highly volatile context. Only recently, in a bold political move, did Türkiye move to carry out long term development projects such as building concrete housing units, with funding mainly from Qatar.[8] Donors that do fund multi-year interventions are better able to support communities in resilience, social cohesion and wellbeing programming areas, according to participants in this research, but their efforts are hampered because the work they support is not integrated with shorter cycle basic needs interventions. Multi-year programmes centring resilience, social cohesion and wellbeing are just one source of support in a largely fragmented, siloed, and non-communicative response focussed largely on meeting basic needs on an emergency basis. Respondents flag that there is insufficient communication across ‘emergency’ and ‘early recovery’ interventions, and note a lack of integration of resilience, social cohesion and wellbeing strategies throughout the response as a whole.

To navigate these challenges, there is no need to shift entirely from ‘emergency life-saving’ response to ‘early recovery’ programming or vice-versa. Respondents emphasise that both are necessary; for example, communities concerned about food security are not going to embrace resilience programmes that are blind to their urgent needs. A closely coordinated complementarity of approaches is needed to empower communities to address the complex set of needs they are facing – from basic shelter, food, healthcare, and hygiene requirements to the less intangible — but equally critical — daunting challenges of bolstering resilience, fostering social cohesion and achieving greater wellbeing. Each aspect of the response is fundamentally interrelated to the others, regardless of where it may be siloed or situated, because resilience is impossible without basic food security, for example, and social cohesion efforts can only succeed if adequate shelter is available and fundamental needs are met. To this end, practitioners advocate strongly for greater communication, coordination and implementation of mutually reinforcing strategies across the northern Syria response.

Indeed, interventions focussed on the provision of immediate, lifesaving aid and those seeking to bolster resilience, social cohesion and wellbeing are fundamentally not at odds for the simple reason that addressing basic needs helps foster resilience, social cohesion and wellbeing, while effective support for resilience, social cohesion and wellbeing often delivers lifesaving results. Respondents to this research emphasised the need for precise localisation in order to achieve lifesaving outcomes through programming in support of resilience, social cohesion and wellbeing. If interventions are predicated on deep understanding of “the nature of each community”[9], “the qualities and characteristics of the social classes”[10] across targeted areas, the “culture and structure of society”[11], and “the historical context of society”[12], then respondents contend that positive, lifesaving outcomes can be achieved through these programming streams.

Programmes that effectively support community resilience, social cohesion and community wellbeing can deliver lifesaving results among targeted populations. In part, respondents attribute these significant perceived impacts to the cross-cutting nature of the concepts of resilience, social cohesion and wellbeing. Participants in this research emphasised that, for example, actors engaged in delivery of essential services and infrastructure development are not targeting the improvement of resilience, social cohesion or wellbeing as specific outcomes of their work per se, but improvements in these areas are nonetheless a direct impact of their successful interventions. According to respondents, a long-term programme to promote food security in northeast Syria offers a specific example of this: by supporting farmers and the agricultural sector over time, response actors contributed to a drastic increase in the availability of affordable bread with respect to vulnerable populations living across the target geography. Access to affordable, sufficient food saves lives, and in turn, food security contributes to improved community resilience, social cohesion and community wellbeing.[13]

Programmes to support resilience provide communities with resources, infrastructure and skills that can help them save lives and endure shocks in unforeseen crises. For example, a resilience programme invested in setting up a farmer’s union in one area before the February 2023 earthquakes. When the earthquakes struck, the union building was used as a shelter and the farmers were able to use skills and resources they had acquired through their work with the union to organise and deliver support to the affected population. There was no need for the farmers to request outside aid, since they were able to pivot their organisational skills and economic resources to deliver support to people in need.[14]

Programmatic Distribution

The community of practice engaged in programming related to community resilience, social cohesion and wellbeing is led by international non-governmental organisations (INGOs), particularly the six members of the Syria Resilience Initiative (SRI, formerly Syria Resilience Consortium (SRC)), a consortium dedicated to the coordination and delivery of programming across these thematic areas. Respondents to this research were not aware of diaspora support for interventions expressly intended to bolster resilience, improve social cohesion or enhance wellbeing. This could be due in part to the reality that projects do not always fall clearly under those concepts, or people are not aware that they do. Diaspora individuals would send money to an NGO to build better tents, for example, but whether delivery of better shelter fits into concepts of resilience and social cohesion becomes a different question that even implementers on the ground cannot clearly answer.

With programming in these areas driven by INGOs and the international donors that support them, resilience, social cohesion and wellbeing programmes are constrained to operate within short contract cycles. While the INGOs leading this work strive to be consultative and empower communities to design and lead programming in these areas, key informants participating in this research agreed that it is impossible to engage with communities to this extent across all target areas. As a result, there is a patchwork of geographies in northern Syria: some communities have years of experience with resilience programming, and some have had no exposure to such interventions. Participants in this research emphasise that these disparities highlight the need for resilience, social cohesion and wellbeing programmes to be streamlined across the entire response. As long as these programmes are effectively siloed and delivered by only a few actors, they cannot reach all communities in need. Indeed, as one member of the team conducting this research observed, very few implementers on the ground know what is meant by “resilience”, “social cohesion” and “wellbeing”, and rather they appear primarily concerned with implementing their own projects within the allowed timeframe. The bandwidth implementers, local authorities and CSOs have to explore concepts like these that are constrained by political and military uncertainty across their areas of operations. They don’t know what will change, when, and how shifts in regional politics or military control on the ground would impact them or their programmes. According to the researcher, this is a factor as to why many response actors and members of affected communities fail to see value in projects related to trainings on human rights violations — in a country rife with them; the context does not allow attendees of such trainings to act on what they learn outside the classroom.

Resilience, social cohesion and wellbeing programmes tend to target both internally displaced persons (IDPs), including those residing in camps as well as those in communities, and host communities living in their areas of origin. Participants raised this as a very positive aspect of these programming streams, particularly relative to more narrowly-focussed emergency relief programmes that can neglect or generate unintended harm for particular groups. Providing one example of the latter, one respondent cited recent emergency support that was rendered available only to earthquake-affected populations earlier this year. The respondent noted that while those affected by the earthquake were host community homeowners who lost houses, the IDP population had nothing to begin with, and even depended on the host community for support. Thus, when the host community suffered impacts of the earthquake, some of these were transferred onward to IDPs, who lost access to some critical resources and support. Nonetheless, emergency relief was available only to those ‘directly’ affected by the earthquakes, and thus was not delivered to IDPs.[15]

Despite efforts and intentions to implement resilience, social cohesion and wellbeing programmes within camp and host communities, access restrictions with respect to certain camps can impede delivery of planned interventions. For further discussion of programming obstacles, including access hurdles and constraints imposed by local authorities, see the below section Programmatic application.

Women-focussed and Women-led initiatives

One female participant in this research, the director of a women’s centre, identified the prioritisation of women’s meaningful participation in resilience, social cohesion and wellbeing interventions to be a particular benefit of programmes related to these thematic areas. Indeed, seven of twelve respondents specifically mentioned women-led activities when identifying resilience, social cohesion and wellbeing initiatives underway in their communities or target areas. However, positive reactions to women-focussed initiatives in certain areas should not be taken as a sign that all such programming is suitable for all communities in northern Syria, respondents cautioned. In certain areas, women-focussed interventions tend to be treated with hostility from local authorities and other key stakeholders. For communities in these areas, the emphasis on women’s rights and political empowerment can be a distinct negative of resilience, social cohesion and wellbeing programmes, unless such programmes are led by local organisations carefully tailoring their activities to the demands of the political and security situation, and remain cognizant of target communities’ basic needs. The director of a women’s centre who participated in this research expressed concern that women’s political empowerment activities in particular may not be appropriate in all areas — including villages in the Idleb countryside. She noted that implementation of such activities should build upon a “foundation of social awareness”, and would not be safe or feasible in the current context, which is marked by fluctuations in the political and security situation.[16] Programmes should be locally-driven and tailored to the specific situation of each community where they are delivered, in order to be delivered safely and effectively.

In what respondents consider a consequence of these specific challenges, participants in this research perceive women-led and women-focussed initiatives to be far more numerous and visible in areas controlled by the Turkish-backed armed groups than in those controlled by the former al-Qaeda-affiliate Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS). For example, a local council near Al-Bab, eastern Aleppo governorate, participates actively in the delivery of resilience programming within its community, including activities focussed on women’s empowerment. Activities for women include political empowerment training courses, livelihood training and vocational courses, as well as workshops on women’s rights. One respondent working in areas under Turkish influence emphasised the impact of interventions to strengthen women’s digital security and equip women with the skills to pursue livelihoods related to the upkeep of phones and electronic devices.[17] Respondents engaged in this geographic area note that members of the council consider these resilience activities valuable, because when delivered along with additional activities to promote food security and further expand access to livelihoods, these interventions can help to “form a unified community, able participate in the emergency response to any natural disasters or deteriorations in humanitarian conditions.”[18]

In Idleb governorate, where women-focussed interventions are particularly difficult, experience of women-led interventions in earlier eras can help to inform future programming. A women’s centre leading an initiative in Kafr Nabl, southern Idleb, prior to its recapture by Government and allied forces in 2020, encountered difficulties in delivering resilience programming as a component of emergency response activities centred on women’s priorities, and enabling women to benefit from the resources of society. The initiative took an integrated approach and operated in collaboration with other response actors and activities,[19] but an observer considers that it faced challenges on several fronts due to its integration of gender-focussed resilience work. First, a general lack of awareness of the concept of “social cohesion” among response actors and community members made programming more difficult than anticipated. Second, the presence and control of extremist actors also constrained programme implementation and impact. While one respondent notes that the integrated, collaborative approach allowed the initiative led by the women’s centre to have greater reach than it would have, the integration of a gendered focus on resilience, social cohesion and wellbeing had a negative impact in terms of its success.[20]

Social Cohesion and Wellbeing

Respondents to this research provided specific examples of the effectiveness of social cohesion and wellbeing programming delivered by response actors as well as by local actors — particularly political fora and local civil society actors. Respondents did not identify programming expressly related to ‘wellbeing’, but rather mentioned programmes targeting social cohesion, or ‘combining’ social cohesion and wellbeing. Some even noted that “considering wellbeing would be a luxury” as they often find themselves responding to urgent needs.[21] Response actors who consider that they are fully occupied trying to meet emergency needs would likely not be well-situated to conduct assessments of wellbeing, however, assessments could be possible if led by other actors in coordination with emergency responders. Because wellbeing can be conceived as more objective or subjective depending on the definition adopted, methods for its measurement vary. Among the more ‘objective’ indicators, researchers can measure and track: education attainment of community members, availability and quality of health services within communities, quality and accessibility of critical infrastructure (such as water, roads, electricity, and internet), the presence safe and secure environments, the availability and perceived fairness of conflict resolution mechanisms, and communities’ economic stability. These could also provide a perspective on the resilience of a community and its institutions. More ‘subjective’ indicators of wellbeing could be measured and tracked to help response actors better understand how available institutions, services and support structures are perceived by community members, allowing a focussed lens on how community institutions function in service of community members. In-depth analysis of both sets of indicators would likely hinge on surveys conducted in target communities, with ‘objective’ indicators tracked through more quantitative questions and ‘subjective’ indicators examined through surveys that rely heavily on qualitative lines of questioning. A combination of these approaches and consideration of both the ‘objective’ and ‘subjective’ indicators could help response actors to better understand the full picture of community wellbeing, track its evolution over time, and respond better to particular wellbeing needs and identify opportunities for support.

While some participants, like those mentioned above, considered ‘wellbeing’ work to be a ‘luxury’ beyond their current scope of attention, others participating in this research expressed confusion as to the meaning of the term. Several respondents conflated the concepts of ‘social cohesion’ and ‘community wellbeing’, and were not able to articulate clear differences in these programming streams. However, they emphasised that these are interrelated concepts and programmes in these areas are implemented jointly through related activities. Participants were able to identify positive outcomes from social cohesion programmes as well as from interventions they consider to combine social cohesion and wellbeing programming.

In one example provided by a participant, a women’s centre in a town in northern Idleb implemented various activities as part of a social cohesion programme, but one respondent identified the most important of these to be vocational training courses for displaced host community women, with an aim to support the sustainability of such courses, in order to foster partnership between displaced women and host community members.[22] According to the participant, these activities helped break a substantial barrier of cultural, customary, and traditional differences between the two communities. From that point, subsequent trainings facilitated greater interaction and integration between women from the two communities. In turn, this enabled members of each community to demonstrate greater acceptance of women from outside their own community. Participants note that by continuing to build on these interventions, women members of different communities will have opportunities to participate in knowledge sharing and pursue their collective political empowerment. One participant based in northern Idleb noted that social cohesion and wellbeing programmes that focussed on economic empowerment might be considered more acceptable by local communities and authorities than those pertaining to political empowerment. This is especially true for gendered interventions targeting women. Notably, the participant observed that when individuals are economically empowered, they are more likely to have political influence and impact when conditions allow.

In contrast, a local response actor also working in areas controlled by Turkish-backed opposition groups, expressed some concern about social cohesion programmes implemented within their target communities. Trainings and workshops centring on documentation, human rights and citizenship were intended to help bolster social cohesion, however, the participant notes that these were not well received by local authorities and as a result were not as impactful for community members.[23] See below ‘programmatic application’ for further discussion.

Programmatic Considerations

Practical obstacles to the implementation of resilience, social cohesion and wellbeing programs vary by area. Instability, uncertainty and fluctuations in the political and security landscapes are generally more acute in Idleb governorate than in other opposition-controlled areas in northern Syria, but there is a risk of anticipated and unforeseen shocks disrupting or impeding programming throughout northern Syria. Infighting among armed groups is more pronounced in northern Aleppo and RAATA than in HTS-controlled Idleb to the west. HTS has a stronghold over internal security in its areas, and actively eliminates competitors. In the east, Türkiye backs a variety of armed groups that compete over trading and smuggling routes, checkpoints, and control of certain towns.

With that said, the opposition’s enclave north of Idleb governorate is more vulnerable to Russian airstrikes and incursions by Government and allied forces. Occasionally, US-led Coalition airstrikes target former or current ISIS leaders alleged to be hiding in the enclave. Since 2020, a de-escalation zone has been agreed between Russia and Türkiye in areas controlled by HTS and the Government northwest of the country. But the enforcement of the agreement has remained susceptible to fluctuations in Turkish-Russian relations. Due in large part to this complex security landscape, challenges to overcome include access impediments, lack of support from local gatekeepers, and a lack of community acceptance.

Access: As mentioned above, respondents noted that where local councils control IDP camp access, these councils need to be engaged as key gatekeepers and essential stakeholders prior to any attempt to deliver programmes in the camp. According to respondents, programmes that are designed without the involvement and support of local councils are blocked; the solution participants identified is to consult with local councils and attain their buy-in prior to implementation. When these councils are engaged at early stages, there are opportunities for collaboration on resilience, social cohesion and wellbeing programmes – at least in certain locations. This is especially true in towns and cities under the military control of Turkish-backed armed groups, where local councils tend to have more independence compared to those in HTS-controlled areas in Idleb where the role of local councils is subsidiary to the centralised Salvation Government.

Local authorities: A respondent described one instance where access was granted but engagement of local authorities was not sustained over time, and social cohesion activities led by civil society actors in areas controlled by Turkish-backed armed groups were not prohibited or shut down, but local authorities did not contribute to the activities. In addition, the local authorities did not respond in any positive, visible manner to the intervention, and did not encourage community members to take part. Based on this, the respondent considers the largest impediment to social cohesion interventions in northern Aleppo to be the roles and interactions of local community members and local authorities with respect to activities and projects.

In this example, the lack of buy-in from authorities for human rights documentation trainings was likely rooted in the reality that many Turkish-backed opposition armed groups in control of these areas are themselves often targeted with investigations and/or sanctions over human rights violations. Recently, two groups were added to the US Treasury’s sanctions list.[24] Despite this challenging environment, documentation trainings — and other activities that are of fundamental importance but high risk — might be better implemented in ways that do not expose participants to security risks, such as online courses. To be successful, these would need to remain under the radar of armed actors. To ensure zero visibility, it might be necessary or helpful for implementing partners to secure the backing of sympathetic, influential local actors and civil society groups to bolster their protection and mitigate the risk of armed actors’ interference. Any activities conducted without discreet but substantial political backing should maintain zero visibility and limited frequency due to security risks.

The disintegrated nature of local governance structures across the northwest of Syria further complicates programming in the area, especially in areas under Turkish influence. There, local councils are largely independent in managing their own areas without a centralised body that could unify and streamline procedures and aid operations across the whole area. Indeed, the Syrian Interim Government (SIG) and Aleppo Provincial Council (APC) are considered to have limited influence and authority across northwest Syria and the affiliations of local councils to these institutions are entirely — or in large part — symbolic. This means that NGOs have to register and get approvals for projects from each individual council, each with potentially different bureaucratic procedures and interests in aid programming. One participant working on aid programmes in the area noted that the most prominent obstacle to resilience and social cohesion programs is the bureaucracy that “local government entities, local councils and other stakeholders suffer from.” This issue may not be as paramount in Idleb governorate, where HTS and the Salvation Government have maintained a centralised control over towns in their area. This high level of centralised HTS control, while contributing to myriad other challenges, has reportedly enabled the standardisation of bureaucratic procedures.

Community acceptance: Any intervention can only thrive if it is accepted and understood by the local community, as only then can it be met with the active participation of the targeted community members. In the example above, where a social cohesion activity failed to attain the support of a local council, the respondent notes that beyond the challenges posed by local authorities, community members’ lack of basic education and awareness vis à vis principles of human rights and equality poses a challenge to social cohesion efforts across these areas. There are three main factors impact buy-in from local community stakeholders. First, local authorities and beneficiaries prefer and are better engaged with activities that provide them with material support, such as food baskets, cash vouchers, or similar tangible benefits, as opposed to others that do not provide immediate gains. Second, trust is important. Programmes become all the more difficult if implementers (and/or their international backers and donors) do not have an established relationship of trust with local influential individuals and authorities. A participant based in Afrin noted that “ideology, connections, relationships, and politics” affect relationships with stakeholders on the ground. Third, target communities are different across different towns and cities. Their needs and circumstances vary, as well as their relationships with other communities of different ethnic and religious backgrounds or areas of origin. This is seen most clearly when implementing programmes targeting host and IDP communities.

Overcoming challenges: According to the participant who described challenges with local authorities and community acceptance with respect to social cohesion programming, both obstacles are best addressed with the same strategy. When several organisations with different areas of expertise and focus collaborated to deliver a project focussed on social justice and gender equality, they managed to engage local authorities more successfully and continuously throughout the intervention and garner more community understanding and support for their activities. By coordinating closely, the organisations involved were better able to navigate stakeholder relationships and attain community buy-in, allowing them to deliver their respective activities as part of mutually-reinforcing interventions.[25]

Through cross-sectoral collaboration, implementing actors can adopt a systems-oriented approach to negotiate access and support for a full range of activities, rather than resilience, social cohesion and wellbeing programmes in isolation. Through close, multi-stakeholder engagement, and information sharing across sectors, collaborating partners can also gain better understanding of community situations, needs, and perspectives. Actors can then tailor activities in line with this greater knowledge base, designing interventions that are better suited to target communities and more likely to be accepted. In addition, when collaborating across sectors, response actors can package resilience, social cohesion and wellbeing interventions with support for basic needs, infrastructure development or other activities that may appear more urgent or necessary to local authorities and communities. With this approach, implementing actors can at once make resilience, social cohesion and wellbeing programmes appear more palatable to local stakeholders as well as present them as more ‘essential’ by situating them as integral pieces of broader interventions.

2. Conceiving Resilience, Social Cohesion and Wellbeing for AFNS

| 1) Best practices that promote systemic, area-based, community resilience, social cohesion and wellbeing comprise fundamental steps that would enable more context-appropriate and impactful programming: improved communication, coordination, and collaboration among response actors and between response actors and local stakeholders.

2) Future AFNS allocations should seek to encourage cross-sectoral collaboration, with resilience, social cohesion and wellbeing interventions mainstreamed across response programmes, and ensure tangible support, assets or investments are coupled with resilience, social cohesion and wellbeing projects. |

Components of Resilience, Social Cohesion and Wellbeing Programming

Based on the interviews and literature review conducted for this research, several critical components are necessary to the more effective application of community resilience, social cohesion and wellbeing programming. First, these concepts are interrelated and interdependent. Attempts to promote one, exclude others, and implement activities in isolation tend to fail in practice. Second, these programming streams are more welcome when packaged with concrete deliverables: community assets, essential infrastructure, support for basic needs. Approaches that silo resilience, social cohesion and wellbeing interventions away from other response activities can confuse or frustrate communities. For example, community members whose basic needs are unmet may resent being asked to spend days attending capacity-building trainings when they consider that their time would be better spent providing for their families’ needs. Interventions that are blind to communities’ complex realities and the critical challenges community members face thus may not be welcome, and will be at greater risk of prohibition by authorities and lack of participation from targeted community members.

Lack of communication, coordination and collaboration within and across clusters hampers all sectors of the response across the northwest of Syria, according to participants in this research. While respondents note that valid security concerns motivate many actors’ efforts to hold information close, they repeatedly shared concerns that this strategy can generate unintended harm for communities. For example, one respondent told of two health actors that each simultaneously undertook to provide their own health centres in Bassouta, south of Afrin city, while no health actors sought to deliver programming in nearby Jindires. By failing to coordinate, the actors in this example created competing health services, confusing community members, diluting donors’ value for money, and failing to extend the reach of lifesaving aid as far as would have been possible with better planning.

To avoid similar outcomes in future interventions, including projects related to resilience, social cohesion and welfare, response actors should adopt an area-based approach. Such an approach must begin by thoroughly assessing the full set of needs and relevant dynamics for communities across a given area, by consulting extensively with community members and examining historical, political, social and cultural factors. To be useful, gathered information must be shared with all relevant actors responding across a given geographic area, so that responders can reach a collective understanding of the ground situation and use this to inform their intervention design and implementation.

With a shared contextual understanding better enabling interventions that are programmatically and geographically complementary, the reach and impact of programmes can be maximised, which ultimately means interventions are as life-saving as possible. This approach allows response actors across various sectors to ensure they are delivering support that at once addresses immediate needs and endeavours to equip communities with the assets and skills to improve their resilience, social cohesion and wellbeing over time. This strategy promotes sustainable, inclusive community self-sufficiency and serves to decrease aid dependency over the programme cycle and beyond. Failure to adopt this approach actually perpetuates aid dependency, as some villages receive two health centres, for example, while others get human rights training or nothing at all, and at the end of a funding cycle no community is equipped with the full set of resources, skills, and tools necessary for its members to provide for their own needs going forward.

Programmes should be designed to endure a longer time horizon than a single funding cycle. As is true across any crisis or conflict response, even multi-year interventions in the northwest of Syria are a waste of funds if similar programmes must be repeated in perpetuity to ensure sustained impact. Investing heavily in area assessments can help optimise localisation, as it helps ensure programmes are appropriately tailored to the specific needs of communities, are understood and embraced by key stakeholders, and are designed and executed in a manner that can be adapted and carried forward by community members at the conclusion of the funding cycle. This approach ensures local ownership of interventions, sustainability over time, and a gradual transition away from aid dependence. When done badly, efforts to localise response activities can entrench inequality, for example by partnering with and engaging only the most ‘capable’ members of civil society and failing to invest in the inclusion and growth of more marginalised groups. Comprehensive area assessments can help response actors identify and navigate these risks, ensuring greater programme success.

3. Delivering on the proposed Resilience, Social Cohesion and Wellbeing approach across northern Syria

| 1) The AFNS can support systems-oriented ways of working towards improved community resilience, social cohesion and wellbeing outcomes through adopting a coordinated, area-based, multi-sectoral approach with heavy investment in localisation.

2) Local humanitarian actors are already equipped with considerable capacity to respond to community needs in northern Syria, but greater investment in key resources, sharing of technical expertise and expansion of efforts into harder-to-reach areas are needed to maximise the sustainability and life-saving nature of the response. |

Practical Recommendations, Informed By This Research

Capacity building for local stakeholders: Numerous respondents to this research emphasised repeatedly that there is a high level of ‘capacity building’ burnout across the northern Syria response and among local stakeholders. Several civil society leaders asserted that communities in certain target areas have plenty of capacity; what they lack is key assets, essential infrastructure, necessary financial resources and safe conditions to meet their own needs.[26] Respondents also noted the ‘capacity’ landscape can vary considerably across communities in northern Syria.[27] Some communities and civil society actors have received a solid decade of support, complete with enough trainings and empowerment activities to render any further ‘capacity building’ useless. Elsewhere, communities continue to struggle in the face of relative isolation, and members of such communities could benefit from capacity building activities. Other communities sometimes have to deal with sudden shocks for which they are ill-prepared to respond quickly, which was seen most clearly in towns impacted by the February earthquakes. Other shocks, like water or energy shortages, or price-hikes due to obstruction to supply routes, could also be beyond what organisations on the ground are able to handle. However, in these harder-to-access communities, capacity building alone will never render local actors able to meet their own needs with zero outside support. Without continued support for immediate needs, investment in crucial resources and a strategy to build their independence and self-sufficiency, communities can attain infinite ‘capacity’ but remain entirely dependent on aid.[28] For this reason, capacity building should never be delivered in isolation, but rather must be tailored to the specific needs of particular actors and delivered as part of a multi-dimensional response informed by communities’ particular circumstances and entailing substantial investment in financial resources and critical assets.

For example, one respondent highlighted that even the most active and impactful women’s organisations in Syria tend to lack the technical expertise and breadth of experience to operate effectively in the northwest of Syria. In this case, the participant suggested that response actors could do more to facilitate knowledge sharing and the provision of technical guidance from external and international sources to women in Syria who already have plenty of ‘capacity’ but could benefit from peer-to-peer exposure and expert guidance.’[29] Another participant emphasised that in certain areas, social cohesion challenges or lack of civil society capacity are of little concern in terms of impeding community resilience and wellbeing; in such areas, the respondent explained, community members are in far greater need of food, water and support for other basic needs than of capacity building activities.[30] In Afrin, for example, one response actor notes that there is only one women’s centre serving communities, but there are Kurd and Arab populations, and occasionally great tension between the groups. While aid actors are focussed on meeting urgent needs, the respondent cautions that there is a high risk of marginalised communities’ emergency needs going unmet, not to mention intercommunal tensions being unaddressed, because response actors target only particular populations and do not collaborate to ensure full geographic coverage. Syrian organisations tend to have only Syrian staff, Turkish organisations have mainly Turkish staff, and they do not communicate or coordinate with one another to reach marginalised communities. The participant notes that this approach fails to address social cohesion challenges across the area, but of more immediate concern, it fails to provide urgent lifesaving aid everywhere it is needed.[31] There may exist a certain set of communities where basic needs are met but local ‘capacity’ is low and delivery of ‘capacity building’ training would be highly beneficial. However, respondents to this research seem to be engaged predominantly in communities that do not meet such a description, and they urge that programming be tailored to visible dynamics across target areas rather than generic assumptions. Capacity building should therefore not be a default programme component, but should instead be considered only where indicated as necessary by in-depth area assessments and partner scopings, and should be elsewhere replaced with more specialised and context-appropriate support.

Coordination and Implementation Networks

To contribute to coordination across the response community — including at the local level — in order to support the application of an area-based, multi-sectoral, holistic approach to interventions, AFNS can adopt the area-based approach described above. In-depth area assessments and partner scopings can provide steering committee members and response actors with a snapshot to identify programming priorities and coordination strategy. The current cluster system appears to have fallen short of enabling cross-sectoral collaboration, with some suggesting it may have contributed to the creation of larger silos within the northern Syria response, but even within these silos there seems to be a lack of communication and coordination among response actors. A full shift to area-based programmes, informed by comprehensive assessments, designed in close consultation with community members and relevant stakeholders, and led by local civil society actors, would provide a structural basis for enhanced coordination and more impactful programming across all sectors, while expanding the reach and magnifying the impact of resilience, social cohesion and wellbeing interventions.

The adoption of such an area-based approach informed by precise contextual dynamics and led by carefully-selected local actors would ensure that each stage of every AFNS-supported intervention is as closely tailored as possible to the local landscape. In turn, this helps ensure that local authorities are considered, engaged and navigated from the earliest stages of programme development. By pursuing early and continuous buy-in from local gatekeepers, response actors can maximise the chances that implementing partners have unimpeded access to target areas, while also investing in key relationships — with local authorities where appropriate and interlocutors where needed — that can help foster community acceptance and active participation in activities.

Advocacy

To advance the proposed agenda with respect to resilience, social cohesion and wellbeing programming, AFNS should engage in advocacy to highlight the interrelated nature of all aspects of the response in northern Syria and to urge all donors to adopt area-based, multi-year funding cycles. Respondents overwhelmingly agreed that community needs are interlinked, not isolated. In consequence, the only way to address immediate concerns while reducing aid dependency is to package emergency assistance with interventions designed to facilitate resilience over time. Encouraging donors to embrace a holistic response strategy rooted in particular area dynamics and executed by local civil society actors would enable AFNS to push forward an effective, durable intervention agenda to meet urgent needs and build community self-reliance in the longer term.

[1] KII #11.

[2] https://www.rand.org/topics/community-resilience.html

[3] See, for example IFRC Framework for Community Resilience, The International Federation of the Red Cross, August 2018. https://www.ifrc.org/document/ifrc-framework-community-resilience

[4] Manca, A.R. (2014). Social Cohesion. In: Michalos, A.C. (eds) Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Well-Being Research. Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-0753-5_2739.

[5] KIIs #3, 4, 5, 7, 8, 9

[6] Wiseman and Brasher, 2008: 358; as cited in What is Community Wellbeing? Conceptual Review. September 2017. Sarah Atkinson; Anne-Marie Bagnall, Rhiannon Corcoran, Jane South With: Sarah Curtis, Salvatore di Martino, Gerlinde Pilkington. At p.4. https://whatworkswellbeing.org/resources/what-is-community-wellbeing-conceptual-review/

[7] KII #9.

[8]https://www.dailysabah.com/politics/turkiye-to-repatriate-syrians-with-qatari-backed-housing-project/news

[9] KIIs #1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and 8.

[10] KIIs #2, 3, 4, 8 and 11.

[11] KIIs #1 and 8.

[12] KIIs #1 and 8.

[13] KIIs #1, 3, 4, 5 and 9.

[14] KII 9.

[15] KII #11.

[16] KII #6.

[17] KII #6

[18] KII #4.

[19] Mazaya Women’s Center collaborated with the Union of Revolutionary Bureaus (URB) to carry out gendered, multi-sectoral interventions to enhance the resilience of women in Kafr Nabl. KII

[20] KII #3.

[21] KII #11.

[22] KII # 6. Participant referenced activities implemented by the Hama Displaced Persons Association, operating across IDP and host communities in northern Idleb, and Start Point, a women’s center in Sarmada, Idleb.

[23] KII # 7.

[24] United States Department of the Treasury, press release, 17 August 2023. https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/jy1699

[25] KII #7.

[26] KIIs #3, 5, 6, 8, 9, 10 and 11.

[27] KIIs #1, 2, 3, 6 and 10.

[28] KII #9.

[29] KII #9.

[30] KII #11.

[31] KII #11.