Beyond Checkpoints: Local Economic Gaps and the Political Economy of Syria’s Business Community

15 March, 2019

Executive Summary

The humanitarian and development community remains fixated on the Syrian ‘war’ economy, as part of their efforts to eschew, mitigate the effects of, or transform Syrian war economy dynamics. In some ways, this fascination is a reflection of concerns associated with indirect effects of the emergency humanitarian response; in other ways, it is a product of contemporary peacebuilding and post-conflict paradigms. Unfortunately, the prevailing conceptualization and approach to the Syrian war economy focuses on its most simplistic manifestations, such as checkpoint bribery; monopolization of cross-line access; or the taxation patterns of proscribed armed actors. This exclusive focus on the ‘symptoms’ of the Syrian war economy, in particular the extractive activities of non-state actors, deliberately obfuscates the role and nature of the current war economy.

To understand the Syrian war economy requires a basic familiarity of the pre-conflict political economy of Syria. Following their coup d’etat in 1970, the Baath party entered into a marriage of convenience with the Syrian business elite whereby the military-dominated state established control over much of the state economy and distributed patronage to supporters in the business community. Following the economic liberalization policies of both Hafez and Bashar Al-Assad in the late 1990’s and early 2000’s, the Syrian economy was increasingly privatized, allowing business community allies of the Syrian regime to benefit from new opportunities previously monopolized by the state-centric economy. Thus, by the time of the Syrian conflict, much of the business community had been systematically incorporated into the state itself, and became a critical component of many state-run activities and services.

The Syrian conflict has devastated the Syrian economy and realigned many relationships both within the business community and between the business community and the Syrian regime; however, fundamentally, the overarching nature of the partnership between the Syrian business community and the state (and accompanying security apparatus) has endured and remains largely unchanged.[footnote] Of note: In this paper, the ‘Government of Syria’ or the ‘Syrian state’ is used to refer to the official Syrian state structure, such as the state bureaucracy, the military, and other official government apparati. The Syrian ‘regime’ specifically refers to the person of Bashar Al-Assad, his family, and his close inner circle, which systematically interlinks with the integrated business community.[/footnote] Without the financial and political capacity to maintain state services, the Government of Syria has increasingly relied on the private sector as a means of replenishing diminished state capacity. While the political-economic structures that had characterized the pre-conflict business-state ecosystem remained in place, loyalist business elites began to take a more active role in supporting the collapsing state – to include militarily- while new loyalist economic actors also emerged to fill gaps created by the conflict.

Of note: In this paper, the ‘Government of Syria’ or the ‘Syrian state’ is used to refer to the official Syrian state structure, such as the state bureaucracy, the military, and other official government apparati. The Syrian ‘regime’ specifically refers to the person of Bashar Al-Assad, his family, and his close inner circle, which systematically interlinks with the integrated business community.

As always, the primary recourse for international donors, UN agencies, funds, and programs, INGOs, and development agencies is to examine ‘war economy’ dynamics and actors through the lens of localization and contextualization, to include local-level sectoral and functional interactions for the objective of service provision. In some cases, there are simple ways of leveraging interventions to directly transform or replace the war economy by filling specific service gaps; in many other cases, attempting to marginalize war economy actors may be a destabilizing force. With the impending conclusion of the cross-border response (on any meaningful scale), humanitarian and development actors will increasingly be forced to directly confront and engage with ‘war economy’ actors (many of whom may also be prominent local governance officials); recognizing the strong incentives to continue activities as well as Government of Syria access and registration impediments, it will likely fall to the donor community to design strategies to identify and mitigate these concerns.

What is the ‘War Economy’?

Despite international preoccupation with the ‘war economy’ – both in Syria and in other development contexts – the concept often remains widely misunderstood. Jenny Peterson, in her landmark book Building a Peace Economy?: Liberal Peacebuilding and the Development-security Industry, defines the war economy as:

“[The] systems in which economic incentives either motivate actors to instigate and participate in political violence, or which facilitate the ongoing conflict by providing a means of financing violent struggle.”[footnote] Peterson, Jenny H. 2014. “Building a Peace Economy?: Liberal Peacebuilding and the Development-security Industry.” Manchester; New York: Manchester University Press.[/footnote]

The fixation on a ‘war economy’ as different from a ‘normal economy’ came to prominence in the early 1990s, ushered in alongside the rise of the concept of ‘new wars’ during, such as the Rwandan Genocide, the Balkan conflict, and the war in Somalia.[footnote]Suhrke, A. Wimpelmann, T. Violent conflict and Intervention. In P. Burnell, L. Ranner, V. Randall (Ed.), Politics in the developing world (4th ed., pp. 196-208). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.[/footnote] These so called ‘new wars’ were generally understood as civil wars, incited by ethnic/sectarian tensions, and characterized by not only open conflict but also diminished ‘normal’ economic activity and opportunity; many academics maintaining this discourse thus argued that war economies arose when local sub-state armed actors extracted resources or established economic activities either to fund their armed struggle or to engage in profit-seeking as its own ends.[footnote]Collier, Paul. 2000. “Rebellion as a Quasi-Criminal Activity.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 44(6): 839–53.[/footnote] In view of the accepted philosophy that many internal conflicts were, to some degree, caused or exacerbated by an underdeveloped or underperforming state, a ‘nexus’ of peace and development studies was introduced as an academic discipline whereby the state and institutional development would underpin the maintenance of peace. The theory was that readjusting political-economic incentives would thereby end conflict and transform a ‘war’ economy into a normal or ‘peace’ economy. This ‘transformation’ continues to be a major component of the broader peacebuilding mantra, and underpins many post-conflict development strategies.[footnote]Miall, Hugh. 2004. “Conflict Transformation: A Multi-Dimensional Task.” Berghof Research Center for Constructive Conflict Management.[/footnote] Indeed, despite having been subject to various critiques, this perspective remains both a basic framework and an inherent part of international peace-building projects, at least as they correspond to war economy transformational mechanisms.

The limitations of this definition of a war economy lies in the fact that it is centered on purely extractive activities conducted predominately by non-state actors. Indeed, in the case of Syria, the ‘war economy’ is a many-headed hydra, a system that identifies and capitalizes on profit-making opportunities, many of which are service provision ‘gaps’ created by the conflict itself. The absence of essential services, formal banking mechanisms, and the free flow of goods and commodities created opportunities; as the Syrian state was either unable or unwilling to fill these gaps, businessmen with the necessary local and national-level relationships stepped in to fill these gaps and earn a profit. Due to pre-existing business linkages to the State, the process of exploiting these gaps was facilitated and in certain cases directly supported by formal government policy. Thus, while it might be convenient to focus on incidents of checkpoint bribery, the reality is that the categorization of economic activities as licit or illicit, ‘war’ or ‘normal’ economy, are artificial distinctions which are less relevant in this particular context.

As noted, the concept of a ‘war’ economy often presupposes that the war economy is an aberration from a ‘peace’ economy, yet from a structural standpoint, much of the ‘war economy’ is a continuation of the pre-conflict Syrian economy, albeit through more decentralized mechanisms[footnote]This continuation of the pre-conflict Syrian political economy into the post-conflict period was been discussed at length by Steven Heydemann, in Beyond Fragility: Syrian Reconstruction in Fierce States.[/footnote]. The fundamental relationships – essentially barriers to entry – have not changed from pre-conflict patterns. For example, one of the most cited examples of the access-based war economy was Mohieddine Al-Minfoush’s monopoly on trade into besieged Eastern Ghouta through the Al-Wafideen crossing. However, Al-Minfoush achieved his control over commercial access through forging (and ultimately purchasing) a relationship with the integrated Syrian business-state elite (in Minfoush’s case, Mohamad Hamsho and Rami Makhlouf)[footnote]Minfoush’s ‘Dairy Godfather’ control of the Al-Wafideen war economy was covered at length in the Economist.[/footnote]. Thus, in some ways entering the ‘access-based war economy’ functionally resembles the process for opening a Mercedes dealership in Mezzeh in 2010.

Syrian Political Economy: From Pre-Conflict to Post-Conflict

Modern Syria Economic Foundation

It is important to investigate how the Government of Syria (and regime) relationship with the business community is broadly structured, and how the current Syrian political-economic landscape was informed by the path dependence of pre-conflict Government of Syria policy. In a sense, the pre-conflict regime structure reflects an early marriage between the Syrian Baath Party political establishment and the traditional Syrian business community. When the Baath party, which was initially comprised of and led by rural minoritarian Arab nationalists, took power in 1963, it adopted a socialist, state-centric economic system.[footnote]Matar, Linda. 2016. “The Political Economy of Investment in Syria.” Studies in the Political Economy of Public Policy. Palgrave Macmillan UK.[/footnote] This naturally came at the expense of the traditional mercantile class. Following the Baath party coup in 1970, and in order to gain the tacit acquiescence of the still powerful Sunni business class, the Baath party co-opted elements of this business class within the nascent state-managed economy.[footnote]This was partially accomplished by incorporating the business community in the nationalization of certain industries, by occasionally granting state contracts, and by facilitating bureaucratic approvals, among other means. Additionally, the Syrian business community became much closer to the state at least partially due to their mutually antagonistic relationship with the Muslim Brotherhood.[/footnote] This marriage transformed the Baath party in some ways in that elements of the traditional mercantile class not only survived the nationalization of the Syrian economy, but also became an integral part of the Syrian Baath party and subsequently gained access to the upper echelons of the Syrian regime.

Neo-Liberalization and the Private Sector State

The marriage of the business sector and the military/security-informed political elite, operating in tandem under a state-driven economic model, defined the pre-1990s Syrian state. Yet beginning in the 1990s, the Syrian economy was transformed by the liberalization policies undertaken by Hafez Al-Assad. These policies in some ways loosened the State’s direct control over the economy, naturally implemented with the full support of the self-interested Syrian business class, and allowed for a more ‘business-friendly’ environment, albeit one that was still supported by and subservient to the state. Perhaps the most important manifestation of this liberalizing shift was the 1991 passage of the ‘New Investment Law No. 10,’ which “permitted Syrian and foreign investors to invest in previously prohibited sectors [to include the industrial sector].”[footnote]Matar, Linda. 2016.[/footnote] Law No. 10 revoked previous statist policies by allowing businessmen to invest in sectors that were previously the exclusive domain of the state or that previously had not existed (e.g. mobile telecommunications); however, in its application, Law No. 10 ensured that these sectors were devolved to the same elements of the business community that had previously formed close relationships with the Syria regime. Future amendments to Law No 10 further advanced the role of the private sector in Syria’s economy, and gradually unwound the state’s monopoly on various economic sectors, to include agriculture, transportation, and industry.[footnote]https://heinonline.org/HOL/LandingPage?handle=hein.journals/intfinr11&div=16&id=&page=[/footnote]

Upon his assumption of the Presidency in 2000, Bashar Al-Assad resumed and expanded the liberalization policies previously set forth by his father, Hafez, and consequently further solidified the marriage between the Syrian regime and Syrian private business. For example, one of Bashar Al-Assad’s reforms further loosened state control on investment, and thus allowed predominately regime-aligned businessmen even greater access to capital. Other similar liberalization policies included increased free trade; privatization of state-owned farms; market-based reforms and the reduction of state subsidies and price controls; banking liberalization to facilitate the establishment of private banks; and drastically increased state use of private sector entities as a contractors.[footnote]For example, the state began to issue contracts for private businesses to construct infrastructure previously built by the state; for example, road repair, garbage collection, water network construction, and construction projects.[/footnote] Mirroring the patterns of elite capture in Russia after the fall of the Soviet Union, businessmen closest to the upper echelons of the Syrian regime were often given preferential access to these new economic opportunities.[footnote]Indeed, Government of Syria elites and prominent businessmen such as Rami Makhlouf, Mohamad Hamsho, Nader Qalai, Issam Anbouba, and Samir Hassan often became major shareholders in many of Syria’s state services or monopolistic privatized companies. For example, Rami Makhlouf at one point reportedly controlled up to 60% of the Syria economy through his ownership of or shares in private companies in telecommunications (Syriatel), oil and gas industrial companies, real estate, construction banking, and retail (Ramak Duty Free Shops). Makhlouf is also a main shareholder in Sham Holding Company, Syria’s second largest holding company.[/footnote] Hence, the course of legislation governing economic liberalization effectively reinforced past practices and further cemented the marriage between business elite and regime. Thus, by the outbreak of the conflict, the distinction between regime and business elite was increasingly blurred.[footnote]Samer Aboud, in his article ‘The Economics of War and Peace in Syria’, categorizes Syrian business elites based on their proximity to the regime. These categories include: an integrated elite who are directly linked to the upper echelons of the regime; the dependent elite who have major economic wealth and are linked directly to the regime; the expatriate elite whose presence outside the country renders them the least impacted by the Syrian regime continuity; and post-2011 the conflict elites who have capitalized on trafficking, smuggling and mediation among different actors in the conflict.[/footnote]

Post-2011

The outbreak of the Syrian conflict in 2011 drastically impacted the Syrian economy and the role of the business class. With the territorial fragmentation of the country, the Government of Syria lost control over major highways, natural resources, and agricultural lands. Many less prominent businessmen fled, while many of those whose interests were intertwined with the ruling political system were heavily sanctioned.[footnote]The geographic fragmentation of Syria and sanctions-induced ‘capital flight’, whereby many businessmen who were outside Government of Syria controlled areas were driven outside the country, and relocated their businesses in neighboring countries.[/footnote] Without the financial and political capacity to maintain state services, the Government of Syria increasingly relied on the loyalist private sector as a means to replenish its diminishing capacity to provide services. New economic actors emerged in parallel with the expansion of the political influence and role of already prominent business elites. While the political-economic structures that had characterized the pre-conflict corporate-state ecosystem remained in place, business elites began to take on a more active role in supporting the collapsing state, to include in sectors previously outside the private sector mandate, such as state security through privately-funded militias.

Additionally, new economic actors ascended into the Syrian business elite, yet without structural changes to the pre-conflict political-economic relationship. Some of these new businessmen were former militia leaders whose war profits were repurposed as ‘legitimate’ start-up capital.[footnote]For example, see Abu Bahar Muawia, a former opposition militia leader in Barzeh who reconciled with the Government of Syria, and then became an extremely prominent NDF commander. Abu Bahar used funds he acquired as a militia commander to open a rubble cleaning and construction company in Barzeh. Of note, Abu Bahar and his partner (another former militia leader, Samir ‘Al-Minshar’ Sarour), were arrested and executed in late 2018. There is some speculation that part of the reason for his arrest and execution was the fact that his business had become a competitor to the business interests of Riad Shalish, President Bashar Al-Assad’s cousin.[/footnote] Other ‘new’ businessmen became prominent by adopting intermediary roles between the Government of Syria and non-Government of Syria armed actors, such as George Haswani, who facilitated the trade of oil from ISIS-controlled areas to Government of Syria-controlled areas,[footnote]This positioned Haswani as a key intermediary in negotiations between the Government of Syria and armed opposition groups, especially in western Qalamoun, namely in Yabroud, Nabk, and Sadnaya.[/footnote] and Ayman Al-Qaterji, who facilitated the crossline trade of agricultural produce (wheat and textile) and oil from ISIS and subsequently Syria Democratic Forces-held areas.[footnote]Over time, this network of intermediate businessmen expanded to include Gulf-based businessmen, such as Mazen A. Tarzi, a Syrian who is a partner in the Kuwait Khurafi Group. Tarzi has reportedly been instrumental in securing the Kuwait Khurafi Group a Government of Syria contract to operate a new Syrian air carrier, Sama Sourya.[/footnote]

The business community will ultimately take part in the post-conflict reconstruction of Syria; indeed, relevant legislations for reconstruction will likely continue to reassert the utility, relevance, and necessity of the regime’s allied business class. [footnote]And likely demarcate the historical neoliberal trajectory of Syria’s political economy.[/footnote] For example, the Government of Syria issued Decree 66 in 2012, which stipulated private sector-led redevelopment of many heavily damaged informal housing areas in Rural Damascus governorate, with the objective of turning low income neighborhoods into higher end real estate developments. Subsequently, Law No.10 expanded the stipulations of Decree 66 to a national scale, and thereby further created opportunities for the business elites to benefit at a national level in the post-conflict space. An additional tool to build state-sanctioned business opportunities for regime-aligned corporate actors are the public-private partnership laws that were introduced in January 2016; these laws essentially authorized the private sector to manage and develop state assets in various economic and service provision sectors. [footnote]Joseph Daher, in his paper “The Political Economic Context of Syria’s Reconstruction” emphasizes that PPP and Law 10 are to be examined as part and parcel of a broader process of deepening neoliberal project in Syria, as they will serve as paved routes for business elites to generate wealth by capturing public assets.[/footnote] For example, in August 2017, Aman Holding Company, owned by Samer Foz, announced that it would take part in the reconstruction of Basateen Al-Razi in Mezzeh, Rural Damascus, in collaboration with Damascus Cham Private Joint Stock Company.[footnote] For more information, See Joseph Daher’s “Militias and Crony Capitalism to Hamper Syria Reconstruction.” [/footnote]

As noted, sanctions and restrictive measures levied against Syrian regime officials and prominent businessmen have had a counterintuitive impact on the war economy by actually empowering some elements of the existing Syrian business community. Indeed, one consequences of sanctions and restrictive measures was to force the regime to increasingly rely on mid-level members of the business community as a means of eschewing targeted individuals and entities. However, new sanctions on Syria have expanded and will target entire sectors of the economy; for example, in November 2018 OFAC warned that it would more aggressively enforce existing sanctions on all actors involved in the oil industry, including shipping companies, insurance firms, and banks that are involved in Syria’s oil industry, which consequently led to widespread oil and gas shortages across Syria. Blanket sanctions have also naturally impacted foreign investment, and without considerable foreign investment and expertise, the Syrian economy will continue to face major gaps in both capital and technical capacity.[footnote]The Syria Report recently addressed many of the key issues surrounding western sanctions in Syria, and made a set of policy recommendations. They essentially argue that any sanctions pursued should be tied to clear objectives, sanctions should expand to include new individuals who came to prominence during the conflict, to maintain banking sanctions despite their impact on the economy, and to reverse measures that are broadly harmful to the population. The report can be found here. [/footnote] As such, the Government of Syria and the Syrian regime will have an even greater reliance on the Syrian business community, as only local, unsanctioned business actors will be capable of generating local capital, as well as leveraging independent business networks to import needed goods.

Redevelopment and reconstruction, alongside the transfer of state services to public-private partnerships and coordination to avoid international sanctions, will further cement the relationship between the Syrian business elite and the state, as represented by the regime. While the Government of Syria and the Syrian regime will likely remain central to dictating the future course of Syria’s economy,[footnote]The regime’s ability to maintain economic centrality cannot be isolated from other broader political factors, to include Governments of Russia and Iran support, US and other western countries policies vis-a-vis Syria, and changes in the level of armed opposition. [/footnote] they will also do so in a manner that benefits the existing Syrian business community and entrenches this community more deeply within the state.

In Defense of Localization and Contextualization

The onset of the Syrian civil war was a major shock for the Syrian economy; however, the actual structure of the Syrian economy, namely the partnership between the Syrian business class and the state (and accompanying security apparatus), continued through the conflict. For that reason, focusing solely on the extractive iterations of the war economy is not useful in understanding the nature of the political military-business alliance. Indeed, the exclusive focus on economies of violence, cross-line trade of certain commodities, the activities of individual businessmen, or armed actor taxation structures may be sufficient at the project-level, but lack the depth an analysis necessary for organizational strategy and policy, especially for those who seek to uphold do-no-harm and other humanitarian principles.

That said, opportunities nonetheless exist for principled interventions. An understanding of the local manifestations of war economy dynamics, as well as the broader state-business alliance in Syria, must be a prerequisite for interventions. Analysis capable of assessing all relevant transformations of the Syrian economy throughout the war – and by extension the indirect impact of humanitarian and development programming – requires the study of more localized political economy relationships and actors at the community-level. Essentially, community-level political economies should constitute the building blocks of Syrian war economy analysis and intervention strategy, rather than generalized extractive-informed perspectives or a recycled theory of change originally devised for other conflicts and contexts, as far removed as Somalia.

Based on the case studies below, one major dynamic that is common throughout Syrian communities is the fact that the ‘war economy’ is in many cases a response to new economic gaps and blockages created by the conflict itself (whether deliberate or accidental determined on a case-by-case basis). As the overarching political/military-business alliance in Syria survived throughout the conflict, those seeking to capitalize on conflict-created needs and gaps necessarily engage with the regime in a manner similar to pre-conflict paradigms. In this way, the distinction between licit and illicit economies is –in many cases– theoretical at best. The actual function of these local war economies is community-dependent, and naturally shaped by the specific needs and gaps, geographical areas, and the response of each local community and its stakeholders.

Case Studies

Below are four case studies that demonstrate how local actors have responded to service gaps during the conflict and in different areas of political control: Case Study 1 concerns Internet service provision in Eastern Ghouta; Case Study 2 details electricity in Duma city, Eastern Ghouta; Case Study 3 describes textile production in Deir-ez-Zor city; and Case Study 4 details Hawala offices in Al-Hasakeh governorate in northeastern Syria. All four cases are similar in that they describe the manner by which the business community filled service gaps caused by the conflict. The way in which these various actors have responded to gaps is in each case quite unique; war economy actors and their services have had a stabilizing effect in some cases, destabilizing in others.

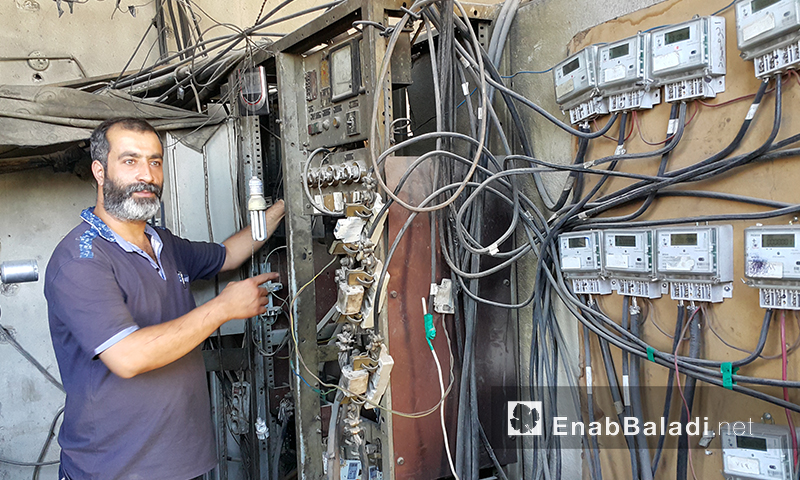

Case Study 1: Electricity Services in Duma City

The Gap

In December 2012, the Government of Syria effectively cut off the majority of electricity services throughout Eastern Ghouta due to the rapidly escalating conflict and the fact that the area had increasingly fallen under the military control of the armed opposition. By June 2013, fuel imports into Eastern Ghouta were cut as well, and the area entered into a de-facto siege that lasted for over 6 years. In response to the significant electrical shortages, communities in Eastern Ghouta were compelled to resort to various other methods of electricity generation (many donor-supported), such as solar energy, biogas generators, wind turbines, and locally produced fuel.[footnote]Plastic was frequently burned as an alternative fuel source.[/footnote] However, these methods were of low efficiency, highly expensive, and under persistent risk of damage due to constant shelling and airstrikes.

Filling the Gap:

Between 2015 and 2016, prominent businessmen and families in Eastern Ghouta, specifically two business families, the Hasaba and the Abd El-Daim families, started to import electricity generators into Eastern Ghouta, in particular to Duma City. Both families were able to import the generators due to their linkages with traders outside Eastern Ghouta as well as with prominent high ranking Government of Syria officials. Despite the siege, cross-line fuel trade continued, albeit at higher prices and lower availability. During this time, members of the Hasaba and the Abd El-Daim families effectively monopolized the generation of electricity in Duma via their imported generators, and also became important fuel traders through the Al-Wafideen checkpoint.[footnote]Indeed, in late 2016 members of the Hasaba and Abd El-Daim families reportedly formed a consortium with another Eastern Ghouta businessman, Mohieddine Minfoush, in order to share the costs imposed by the Government of Syria over cross-line trade networks.[/footnote]

Maintaining the Gap:

The Government of Syria established control over Duma City on May 2018 following intensive aerial and ground attacks that left the city heavily damaged. Essential services such as water, electricity, and shelter have yet to be restored in many communities. Notably, prominent families and individuals that had played a significant economic role during the siege have retained their prominence as service providers and more recently as local governance officials. In fact, members of both the Abd El-Daim and Hasaba families won seats in the current local council of Duma in the recent local elections on September 16, 2018. These two families have also maintained their monopoly over private generators, and are reportedly currently lobbying against the restoration of electrical networks with the Government of Syria Electricity Ministry, in an attempt to maintain economic interests. In the meantime, there is very little public electricity in Duma.

Case Study 2: Internet Services in Eastern Ghouta

The Gap

Due to the cessation of Government of Syria-provided electricity to Eastern Ghouta in December 2012, telecommunication and Internet services which were linked to landlines and electricity networks, effectively ceased in many parts of Eastern Ghouta. While some areas located closer to Damascus city were still capable of linking to Syriatel or MTN Internet connections,[footnote]Syriatel and MTN are the two telecommunication companies in Syria.[/footnote] the connection was reportedly intermittent and slow. Additionally, with shelling and airstrikes targeting nearly every community in Eastern Ghouta, the remaining Internet-related physical infrastructure had been heavily damaged by 2013. At this time, neither armed opposition groups nor local administrative entities were capable of restoring connectivity.

Filling the Gap :

In 2012 and 2013, a group of local businessmen in Eastern Ghouta installed a set of Internet ‘bridges’; these bridges connected to satellites Internet networks and thus provided Internet access to many residents of besieged Eastern Ghouta. To ensure the continuity of the service, business owners regularly installed solar panels to power these bridges. This approach was so effective that Internet service in Eastern Ghouta remained remarkably functional, and was -according to local researchers- faster in besieged Duma City than in Beirut. Several businesses provided this ‘bridging’ service in Eastern Ghouta, the most prominent being the Moslim Network, Al-Keresh Network, and Bro Net network. Local sources indicated that their internet services were relatively affordable throughout this period of time, though it is unclear whether other subsidies/funding streams were involved.

Maintaining the Gap

Following the Government of Syria military campaign between February and April 2018, most satellite bridges were destroyed, and telecommunication and Internet services are now largely provided by Syriatel. Some local telecommunication companies that had arisen during the conflict continued activity after the opposition’s capitulation, such as the Moslim and Al-Kersh Network, albeit with drastically reduced reach and capacity; yet of note, both networks were able to continue functioning only by negotiating an affiliate relationship with Syriatel through which both companies essentially became local subcontractors. Formal Internet service provision through Syriatel remains only partially functional. For example, despite the allocation of 500 Internet ports to the city of Saqba, only 100 actually work. This lack of functionality is primarily due to the fact that Syriatel Internet ports are directly linked to phone networks, which are not yet restored; phone network restoration has reportedly commenced in some areas, but has yet to be completed. Additionally, Syriatel Internet services requires access to the electrical grid, unlike the former satellite services that depended on solar power to charge the Internet routers.

The availability of Internet service continues to vary across communities in Eastern Ghouta. However, in this case, the restoration of state-sponsored telecommunication and Internet service has actually reduced the availability and speed of Internet for many residents. The provision of Internet service in Eastern Ghouta highlights cases in which war economy dynamics can (at least temporarily) have a beneficial effect on local community service provision. Additionally, one explanation for the relative functionality of the Internet in Eastern Ghouta was due to the fact that it was never centralized under one businessman, and, instead, remained a collection of local businesses. Now that the Government of Syria has retaken control of Eastern Ghouta, Syriatel has become the primary Internet service provider and resumed its monopoly on Internet service provision.

Case Study 3: Agricultural Transportation in Deir-ez-Zor City

The Gap

The destruction of local production factories and processing facilities has been hugely detrimental to Deir-ez-Zor’s economy. The local population of Deir-ez-Zor was heavily dependent on agricultural outputs, of which wheat and cotton were the most important. Many of these raw agricultural products were transported to Deir-ez-Zor City, where they were processed and then distributed onwards. Beginning in mid-2014, with the majority of the city under the control of ISIS,[footnote]ISIS destroyed numerous factories in Deir-ez-Zor in order to sell factory equipment and building materials for scrap.[/footnote] Deir-ez-Zor was heavily bombarded by both the Government of Syria and the U.S.-led coalition. Many agricultural processing facilities were destroyed, to include the largest textile production factory in Syria, which was damaged multiple time throughout 2012-2013, and finally rendered out of service by 2014 due to the fact the cotton gin was stolen by ISIS. Heavy damage to these Deir-ez-Zor-based factories and facilities necessitated that local producers and traders find alternative means to process raw commodities.

Filling the Gap

A local ‘war’ economy developed to transport raw agricultural materials to processing plants elsewhere in Syria, largely to Damascus. The Sarraj Company, which is a prominent local Deir-ez-Zor trucking and transportation company led by the locally prominent Sarraj family, filled the gap created by the destruction of these agricultural processing facilities (especially the Deir-ez-Zor textile factory). The Sarraj Company created transportation networks linking local agricultural producers, especially cotton farmers, to processing facilities in Damascus city. These transportation networks were extremely difficult to establish, and necessitated the Sarraj company to negotiate access through both ISIS and Government of Syria-held checkpoints. The Sarraj company heavily profited from transporting these unfinished goods (especially cotton) to processing factories in Damascus.

Maintaining the Gap

The Sarraj Company is now one of the most important economic actors in Deir-ez-Zor, and the Sarraj family wields considerable political influence at the local level. Reportedly, the Sarraj company has begun to heavily lobby the newly-elected Deir-ez-Zor City council to postpone rehabilitation of the textile production plant in Deir-ez-Zor in order to maintain their trucking-related business interests. According to local sources, the Sarraj company’s lobbying efforts have been successful, and there are no current plans to rehabilitate the textile factory in Deir-ez-Zor city.

Case Study 4: Hawala Offices in Al-Hasakeh

The Gap

Prior to the conflict, expatriate money transfers and currency exchanges in northeastern Syria were largely conducted through Western Union offices or Syrian banks. However, the enforcement of sanctions on the Syria National Bank and many private banks as well as the plummeting value of the Syrian Lira rendered formal money transfer businesses non-functional. In 2013, numerous informal money transfer offices, known as ‘Hawala’ networks, began to open offices across all of Syria; these offices initially existed to support expatriate remittances but very quickly shifted to handle the large influx of cash sent by humanitarian organizations and armed group supporters. Thus by 2014, Hawala offices assumed a position of key importance by serving as a bridge for both humanitarian and non-humanitarian support.[footnote]Cross-border aid and development agencies have adopted a series of compliance measures to maintain their ability to fund and implement projects inside Syria. For despite the UNSC passing resolution 2165 allowing cross border humanitarian actions, unilateral restriction by US and EU specifically, added to the basic humanitarian policies such as ‘do no harm’, have created major hurdles in the implementation of humanitarian projects. INGOs have therefore adopted due diligence measures, and resorted to informal transfer of money via Hawala offices to ensure the continuity of their projects. National Agenda for the Future of Syria (NAFS 2016) extensively reviews these challenges, in its report: Study on Humanitarian Impact on Syria Related Unilateral Restrictive Measures; key finding listed in the report is that is that humanitarian actors find transfer of money easier to carry from Iraq into Hasakeh governorate, in comparison with transfers from Lebanon, Turkey and Jordan.[/footnote]

Filling the Gap

According to local researchers, the Kurdish Self-Administration facilitated the establishment of several new Hawala offices in 2014 that were owned by individuals closely aligned with the Kurdish Self-Administration or the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF). In addition to supporting the creation of new ‘trusted’ Hawalas, the Kurdish Self-Administration also sought to sideline non-affiliated or ‘untrusted’ hawalas. The sidelining of these hawalas was largely accomplished through both bureaucratic obstacles (rejection of approvals) and taxation; the Kurdish Self- Administration Monetary Directorate requested a total of $50,000 as an insurance deposit, plus a $5,000 fee to establish a hawala office; subsequently, hawalas would pay annual commercial taxes, similar to other businesses in Kurdish Self-Administration governed areas. However, local sources indicate that the newly established Hawala offices with links to the Kurdish Self- Administration were often ‘exempted’ from initial fees and deposits, and requirements linked to transaction and profit disclosures, thereby reducing internal barriers and increasing competitiveness. The proliferation of ‘trusted’ hawalas indirectly benefited the Kurdish Self- Administration by affording it access to external transactions beyond the scope and scrutiny of international banks, governments, and other regulatory authorities, while also providing the Self- Administration with indirect oversight over inbound transactions.

At present, three of the most important Hawala offices in SDF-controlled Al-Hasakeh governorate are:

- Al Bouti for Money Exchange: located in Tal Hajar and owned by sons of Abd Agha Al Bouti, Al Bouti for Money Exchange has shareholders from the Haso and Saadi families; both the Haso and the Saadi families are linked through familial relationships to senior SDF commanders.

- Ayman Kalash Company: also located in Tal Hajar and run by Ayman Kalash, in partnership with Mahmoud Haj Qasem. Mahmoud Haj Qasem is the owner of Alaz for Logistics, a major contractor that provides support to INGOs and registered with the Kurdish Self-Administration. Members of Qasem’s family are known for their direct linkages to the PKK. The Kalash Company has branches throughout Syrian territory and abroad.

- Norjan for Money Exchange: located in Mofto neighborhood, according to local sources several of the owners of Norjan for money exchange have been affiliated with the PKK since 2003, before the Syrian conflict. Norjan for Money Exchange works closely with the Kurdish Self Administration; indeed, two Asayish patrols are called by Norjan for Money Exchange on a daily basis, at the beginning of the day and at the end of the day, to protect their vehicles used to transfer cash.

Maintaining the Gap

In this case, there is no need for local business elites to pressure the governing authority to artificially maintain a service gap that they can benefit from filling. The broader financial infrastructure constraints will make transferring money to Syria very difficult for the foreseeable future. However, in the case the Kurdish Self-Administration, the absence of a formal banking system has allowed for internal profit generation, oversight over most financial transactions, and access to external financial transfer mechanisms. In fact, the primary driver for entrance into the hawala sector appears not to be profit generation, but rather direct control over a quasi-banking structure.

The Kurdish Self-Administration will attempt to maintain a monopoly over money-transfer mechanisms in its areas of control. In this particular example, the Kurdish Self-Administration is not necessarily deliberately maintaining a service gap, but rather preventing ‘untrusted’ actors from entering the market. It is nonetheless important to note that the future of current hawala actors in northeastern Syria necessarily hinges on the political future of the Kurdish Self-Administration and the stipulations and nature of a negotiated settlement with the Government of Syria.

Conclusion

Current academic and development frameworks for analyzing and transforming ‘war’ economies are flawed. Approaches appear unfamiliar with the Syria and recycled from other conflict contexts. Perhaps as a consequence, current approaches insist on the division of economies into ‘licit’ and ‘illicit,’ for indeed checkpoint bribery is the lowest common denominator unifying Syria with South Sudan. Yet Syria is not South Sudan, Afghanistan, or Somalia. Thus, while past credentials and experience may be relevant for curriculum vitae, they cloud and obscure approaches and ‘best practice’ for Syria. The unit of analysis for Syria-specific policy and strategy should be Syria, and in the case of the Syrian ‘war’ economy, an acknowledgement that while an ‘extractive’ war economy does exist, it is overshadowed by an economy that appears to blur conflict and post-conflict, state and business. Bashar is not Basheer.

As demonstrated in the case studies above, the local war economy in Syria is often a continuation of pre-conflict local economies and may even be construed as a local response to gaps created by the conflict itself. War economy actors capitalize on the new conflict economy, which cannot easily be disentangled, sidelined, or isolated from the post-conflict space, especially as these actors are legitimized through policy and local elections. A better approach to analysis of ‘war’ economy actors would be a renewed focus on localization and specification. Manifestations of the war economy, the actors involved, and the degree to which the war economy impacts stability in Syria can only be understood properly at the community and ‘project’ level. Whether spoilers or stabilizers, stakeholders should also be understood through a functional framework, which is to say the extent to which each actors contributes to or hinders the restoration and availability of local services. Access to service provision and livelihoods – the end state for humanitarian, stabilization, and development interventions – may involve partnering with unpalatable actors in certain contexts. Yet, in many cases, INGOs and development actors have already indirectly partnered with these actors during earlier stages of the conflict, and actively reinforced their local prominence. That said, post-conflict development does not necessarily require a direct partnership with Syria Trust or Rami Makhlouf.

Key Takeaways

1: The Syrian war economy should be viewed as a continuation of the ‘peace’ economy. Adopting a simplistic, extractive-focused approach to the Syrian war economy is problematic in the case of Syria, both due to the political-economic history of Syria and on the ground realities created by the conflict; the cases studies presented in this paper demonstrate how contextualization, specificity, and function are key components to assessing ‘war’ economy dynamics.

2: Syrian war economy actors cannot be isolated from their local political economy. War economy actors may not always be political officials, but in almost every case private sector power-brokers maintain linkages to the political-economic nexus that shaped the pre-conflict Syrian economy; moving forward, many ‘war economy’ actors – whether new or old – will remain politically prominent, and the symbiotic relationship between political authority and economic activity will continue.

3: War economy transformation needs to consider the way in which new economic actors are filling gaps that existed due to the conflict, and to what degree this benefits the community. All of the actors in the case study above were or are providing a badly-needed service to local communities and local economies. To take a reflexive stance against these actors, or to attempt to marginalize them on principle, may be deeply destabilizing in the short term.

4: Now that the active conflict is ending, there is a need to shift from an actor-centric to a community-centric view of war economy transformation. Essentially, the question to be asked should not be ‘how do we mitigate the effects of certain economic or political actors’ but instead ‘what needs to happen to make the community more economically functional and stable’? By focusing exclusively on actors at the expense of the broader community level context it will be extremely difficult to attempt any programming in consideration of the political affiliation prerequisites to doing business in Syria.

5: In some cases, direct INGO/UN/Donor-driven ‘filling’ of gaps could have powerful effects on war economy transformation. However, these efforts will be directly counter to war economy actor interests, with associated programmatic risks. For example, Case Studies 1 and 3 illustrate how war economy actors initially filled a gap created by the conflict, but are now impediments to the restoration of services and livelihoods. International development interventions that could negotiate and fill these gaps would be positive and potentially be transformative.

6: In other cases, legitimizing ‘new’ economic actors may be the most stabilizing solution on a community level. For example, in Case Study 2 detailing internet service provision in Eastern Ghouta, the transition from pre-conflict to post-conflict has involved the formalization of service providers whose business models arose from filling conflict-specific gaps and whose services were, on the whole, quite effective. Interventions that reinforced and supported these sorts of economic actors, despite their relationship to the ‘war economy’ would be positive. Additionally, certain ‘war’ economies, such as the hawala offices in Al-Hasakeh, are difficult to alter or indeed transform, for the benefits are as much political as economic and the current response – especially humanitarian – relies heavily on the continued their functionality.

7: Sanctions or restrictive measures that target individuals will continue to increase the reliance of the Syrian regime on the unsanctioned business community; similarly, sanctions or restrictive measures which target sectors of the economy will likely create gaps which can be exploited by war economy actors. Indeed, a major component of the Syrian business community’s current prominence within the Syrian regime and local governance structures is due to the fact that they are capable of circumventing sanctions. This does not mean that sanctions or restrictive measures should be withdrawn; continuing to target individuals is indeed an important point of political leverage, so long as the purpose of the sanctions is clearly defined. However, sanctions that target entire sectors of the economy may needlessly create economic gaps and blockages, which will only punish Syrian civilians and strengthen those Syrian business community actors that have most profited from the conflict.